In her Ancient China and the Yue: Perceptions and Identities on the Southern Frontier, c. 400 BC-50 CE, historian Erica Brindley opens the book with a chapter entitled “Who were the Yue”?

That may seem like an easy question to answer given that starting from the final centuries of the first millennium BCE one can find many references in Chinese sources to “Yue” 越/粵 peoples who lived to their south, peoples who were sometimes also collectively referred to as the “Bai-yue” 百越/百粵 or “Hundred Yue.” So surely it must be possible to go through those sources and get a sense of who those people were and to piece together some of their history.

In actuality, however, that is not the case, and in this chapter Brindley clearly documents how little we can actually determine with certainty about the Yue from early Chinese texts.

The biggest problem with the term “Yue” is the fact that we can see in early Chinese sources that it was used by Chinese authors to label other peoples. However, there are very few instances when we can see the peoples that the Chinese called “Yue” using it to refer to themselves.

To quote Brindley, “We do not know, for the most part, what the Yue. . . actually called themselves, nor are we aware of the types of ethnic and cultural distinctions they drew among themselves.” (22)

Chinese authors viewed these other peoples as their inferiors, and at times referred to them indiscriminately as “savages” (man 蠻; manyi 蠻夷).

At the same time, however, Brindley also points out that a term like Bai-yue “seems to possess a more culturally and ethnically laden significance” than the terms for “savages.” (32)

Therefore, in this chapter Brindley tries to see what we can actually determine about any cultural or ethnic distinctions that the term “Yue” might have referred to, and she does that in this chapter by looking at textual evidence.

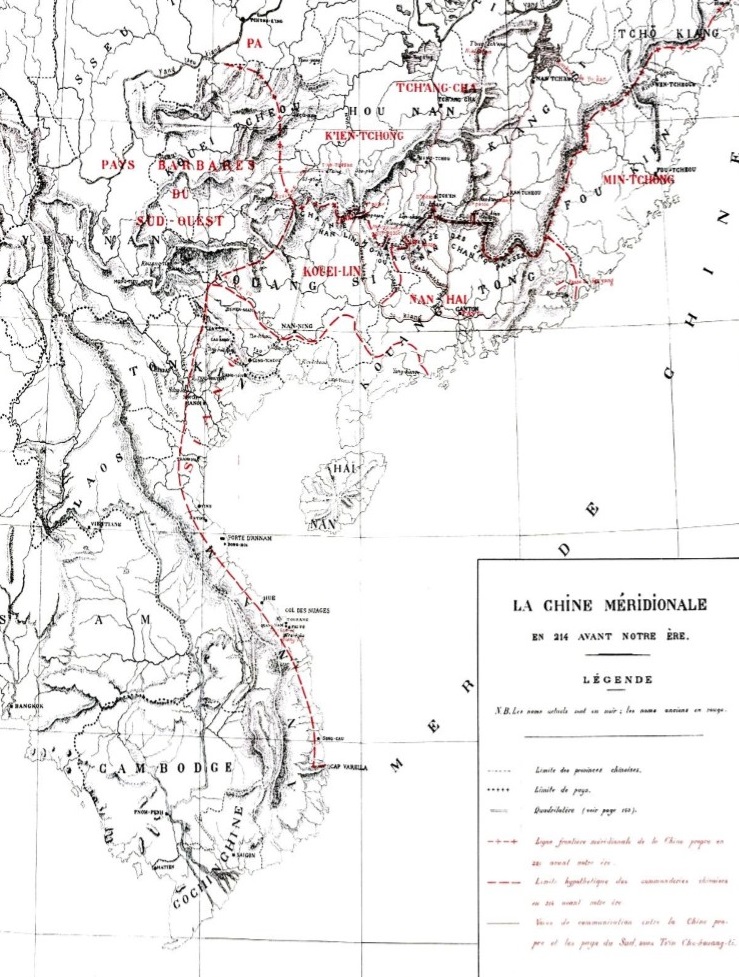

The term “Yue” was first used by Chinese authors around the sixth century BCE to refer to a kingdom just to the southeast of the Central States (Zhongguo 中國), or the area that we can think of as “the Chinese world.” Scholars generally situate the location of this kingdom south of the Yangzi River somewhere around the area of what is now northern Zhejiang Province.

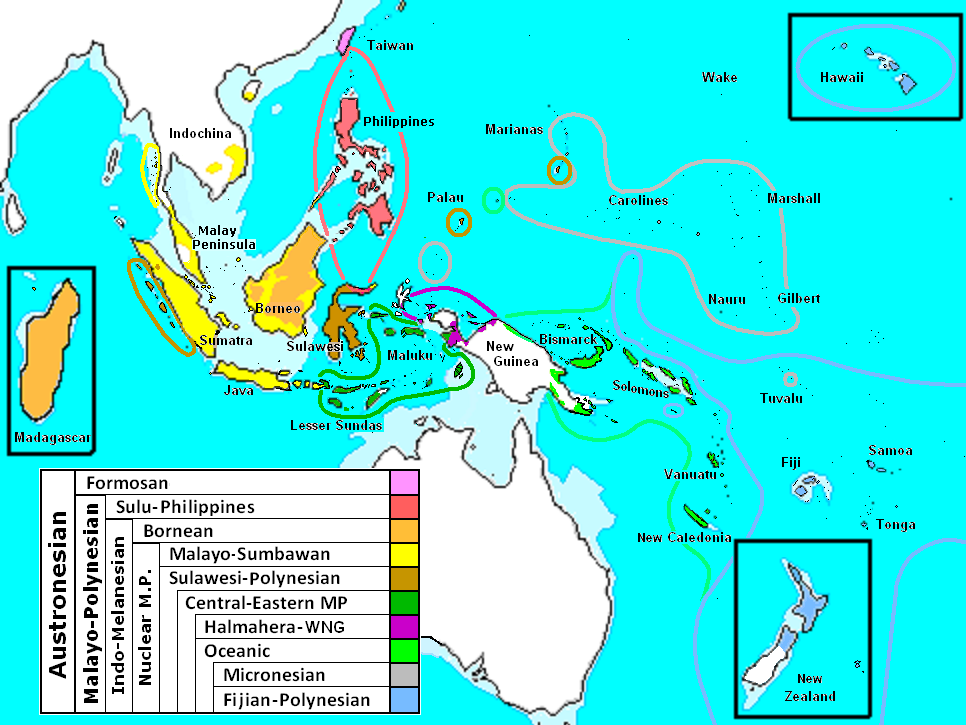

Who were the people who lived in this Yue kingdom and what language did they speak? This cannot be answered with any certainly, but Brindley writes, “given that the southeastern Chinese mainland was likely the homeland of the native inhabitants of Taiwan, one may be justified in thinking about the groups of people on Taiwan as akin to the ‘Yue’ in southeast coastal China.” (25)

And given that people from Taiwan are believed to have migrated away from there into island Southeast Asia and into the Pacific, “in studying the history of the Yue on mainland East Asia, we are addressing the likely history of proto-Austronesian peoples who were linguistically related – possibly even genetically and culturally related, too – to the greatest maritime colonizers of the pre-modern world,” the Austronesians. (25)

However, Chinese writers at times referred to peoples in southern China and as far to the southwest as Guangxi and northern Vietnam as “Yue” too, and as Brindley’s chapter on linguistic evidence demonstrates, there was no single language spoken across that vast swath of territory.

This is what the term “Bai-yue” or “Hundred Yue” implies. It implies that there were many different groups of people living in that region. So early Chinese obviously detected some kind of differences, but then they used the same term to refer to peoples that must have been different in one way or another.

So how can we determine what those differences were? And can we detect any connections between any groups?

These questions are extremely difficult to answer and Brindley’s discussion of the term “Ou/Âu” 甌, another term that was used to refer to some groups in the region, demonstrates that perfectly.

In the third century BCE there was a successor state to the earlier Kingdom of Yue somewhere around Zhejiang and Fujian provinces that was known as Yue Donghai/Việt Đông Hải 越東海, or “Yue of East Sea.” Its capital was at a place called Dong’ou/Đông Âu 東甌, or “Eastern Ou,” and in the second century BCE this kingdom was often referred to by that name – Dong’ou.

Meanwhile, at that same time there were people who lived in the area of what is today Guangxi Province (and perhaps northern Vietnam) who were referred to as the “Western Ou” people, Xi’ou/Tây Âu 西甌.

These terms – Eastern Ou and Western Ou – certainly look like they must be related, but there is no evidence that can demonstrate that.

Hence, Brindley writes that “The question as to why the term “Ou” was used to describe two different sets of Yue peoples, thousands of kilometers apart from each other (one in Fujian, the other in Guangxi/northern Vietnam), still remains to be answered. To date, I have found no decisive explanation.

“Perhaps the two groups shared some type of outward, distinguishing marker, such as a particular pattern or placement of a tattoo, which made Sinitic peoples group them into the same category.

“Perhaps the shared use of the term is purely coincidental, and that each group referred to themselves using a term in their own languages that sounded similar to non-native speakers.

“Perhaps they were actually the same branch of people, some of which had broken off to migrate westward along the coast.” (35)

I think it’s fantastic that Brindley demonstrates that early texts cannot enable us to definitively answer a question like “Is there a connection between Eastern Ou and Western Ou”? Providing multiple hypothetical answers to that question makes that clear.

However, hypothetical questions like these open a door that can lead us even deeper into the realm of uncertainty because in order to be able to accept as possible even some such hypothetical answers would require certain conditions that we do not have evidence for.

For instance, if Sinitic peoples grouped these two peoples together because they shared a distinguishing marker (which sounds completely logical), for that to happen, some Sinitic person (or people) would have had to have been in contact with peoples who lived thousands of kilometers apart from each other, and would have had to have identified those similarities, and then that person’s (or peoples) observation would have had to been transmitted to others so that it eventually became recognized as the name of those peoples. That is not impossible. . . but those are nonetheless difficult conditions to meet.

Similarly, if Western Ou was connected to Eastern Ou by migration, shouldn’t there be some evidence of this? If, for instance the people who migrated were from the ruling elite (which is much more likely than a commoner migration), wouldn’t that have been documented? We know, for example, that Emperor Hui of the Han (r. 195-188 BCE) officially recognized a descendent of the king of the earlier Kingdom of Yue (Goujian) as king of the Kingdom of Dong’ou.

In other words, the Han Dynasty knew that there was a connection between rulers of the Kingdom of Yue and the later Kingdom of Dong’ou.

So if the Western Ou were elite migrants, it would seem likely that this would have been known and documented, as the Han knew who the ruling elite of the surrounding kingdoms were, and how they were related.

The easiest hypothetical answer to accept is that the similarity of the two names is purely coincidental. But here again, what was the exact nature of the “coincidence” that led to the similarity these two names? We don’t have any way of knowing for certain.

These comments are not meant to criticize Brindley’s point. Quite to the contrary, what is so fantastic about Brindley’s discussion of the textual information about the Yue is that she doesn’t determine for readers what she thinks they should believe, but instead, shows readers the limits of what we can determine.

Not being able to gain a clear sense of who the Yue actually were and what the differences and connections between groups actually were is, I have to admit, frustrating. I would like all of this confusing information to be clarified for me! I want to see a clear picture of who the Yue were!!

But ultimately that is impossible, because there are so many questions that cannot be answered based on the existing evidence.

So while Brindley does not answer the question that is the title of this chapter – “Who were the Yue?” – the fact that she presents readers with the available textual evidence and clearly points out the problematic elements in these sources is nonetheless an incredibly important contribution.

If we cannot know something with certainty, we at least need to be certain about what it is that we cannot know. Brindley provides precisely that kind of certainty in this chapter.

This Post Has 2 Comments

_ I think , the people living in those regions did’nt call themselves ” Viet ” , that term means :crossing over , beyond .(the river) . It’s is a geographical term , designating the whole region south of the Yang zi

_ the ” Chinese ” for every direction gave the barbarians a generic name : south , nam man ; north , bắc 狄 địch ; east 夷 đông di ( i.e.Japanese ); west , tây 戎 nhung

Although for Confucius ” within the four seas , all men are brothers ( Tứ hải chi nội giai huynh đệ , 四海之内皆兄弟 )

the barbarians were beyond the pale

_ Ou 甌 = vase , tub , bowl , cup . Maybe the Ou (whether eastern or western) had some kind of remarkable sacrifical or ornemental vase or utensil

_ Ou 歐 for Europe is only phonetic transcription