There are people in Khammouane Province in Laos who speak a language known as Saek (Sek). In the twentieth century, Western scholars struggled to identify what language family this language belongs to. The earliest scholars claimed that it was Mon-Khmer, but eventually French linguist André-Georges Haudricourt made a convincing case that it was a Tai language, and more specifically, a Northern Tai language.

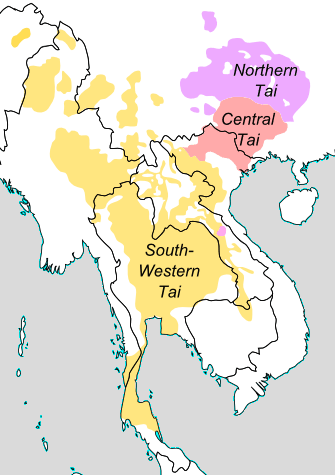

Linguists believe that Tai languages emerged in the area of what is today Guangxi Province in China. Out of some proto-Tai language that existed some 2,000 years ago emerged Central Tai, Northern Tai and Southwestern Tai. Of these three, Southwestern Tai is the one that emerged the latest. Linguists now say that it emerged around the eighth or ninth centuries CE, and that its speakers started to migrate away from the “Tai homeland” at that time as well.

As the map below indicates, these three branches can be identified with different areas, and the place where the Saek language is spoken is in an area where one would expect to find Southwestern Tai speakers, not Northern Tai speakers.

Therefore, the existence of the Saek language has long been seen as a “mystery” that needs to be solved.

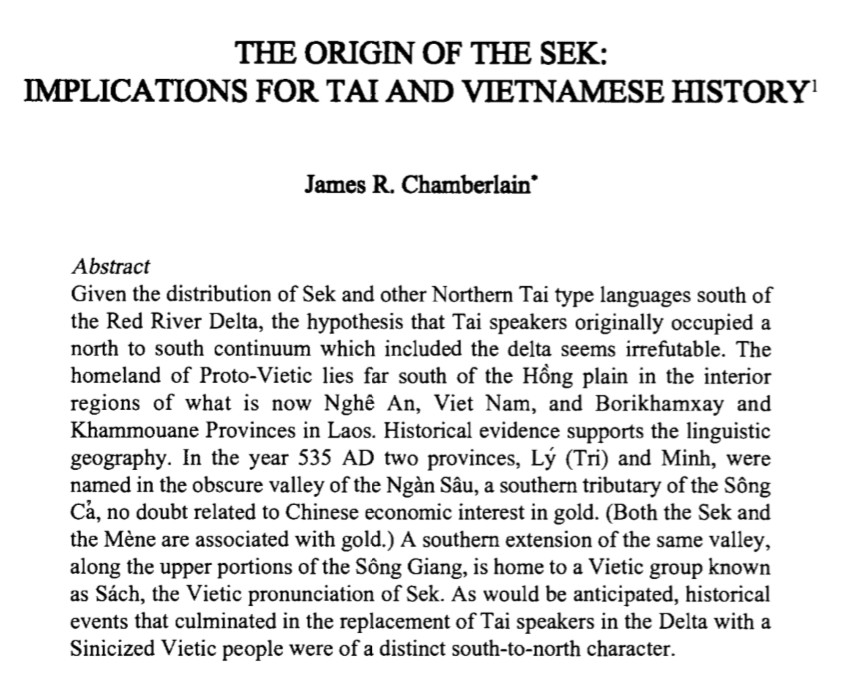

In 1998, linguist James R. Chamberlain published an article in The Journal of the Siam Society entitled “The Origin of the Sek Implications for Tai and Vietnamese History” in which he sought to solve that mystery. In this article, Chamberlain argues that the presence of a Northern Tai language in Khammouane Province in Laos is proof that the entire area from Guangxi to Khammouane Province had been originally inhabited by Tai speakers.

To quote, Chamberlain states that, “Given the distribution of [Saek] and other Northern Tai type languages [which he doesn’t talk about] south of the Red River Delta, the hypothesis that Tai speakers originally occupied a north to south continuum which included the delta seems irrefutable.”

While Chamberlain expressed confidence in this hypothesis, he provided absolutely zero evidence that could demonstrate the existence of Tai-speakers in the Red River Delta.

Instead, he simply assumed that this must be fact, and then he looked in Keith Taylor’s 1983 work, The Birth of Vietnam, for evidence of Vietnamese speakers moving northwards (And the information that he cited here is not from the problematic first chapter that I mentioned in an earlier post. What Chamberlain cited is information that Taylor recorded accurately, but which Chamberlain interpreted in ways that the sources do not support, and which I suspect Taylor would not agree with either.).

In that book Chamberlain found, among other examples, that in 722 there was a rebellion that emerged from the southern frontier of the area that was under Chinese control at that time that was led by a man by the name of Mai Thúc Loan.

Known also as Mai Hắc Đế, meaning “Mai the Black Emperor,” most historians (including Taylor whose work Chamberlain bases his interpretation on) would, I think, conclude that this was a rebellion led by some non-Vietic people, like the Cham. However, Chamberlain argues that this was “the true ancestors of the modem Vietnamese” (42) who were moving northward into territories that were dominated by Tai-speaking peoples.

What is more, in his conclusion he states that, “The precise dates when the ethnic Vietnamese actually replaced the Tai in the Delta are uncertain, but this must have occurred sometime between the seventh and the ninth centuries.” (44)

In other words, Chamberlain came up with a theory that the Red River Delta had originally been inhabited by Tai-speakers and that Vietnamese-speakers only “replaced” Tai-speakers at some point between the seventh and ninth centuries CE. What is more, that theory was based on a single piece of evidence – that there are people today who speak a Northern Tai language in Khammouane Province in Laos.

On its own that is not sufficient evidence to support such a broad claim, but now even that single piece of evidence has been challenged.

In 2012, linguist Pittayawat Pittayaporn presented a seminar paper entitled “Saek as a not-so-aberrant Tai language” in which he argued that many of the features that have surprised linguists about Saek can easily be explained as the result of changes that took place through contact with other language speakers, particularly Vietnamese.

I’m not sure if this means that we can now classify Saek as a Southwestern Tai language, but even if we can’t, this single example is still not sufficient evidence to argue that “Tai speakers originally occupied a north to south continuum which included the [Red River] delta.”

This, however, is exactly what Ben Kiernan argues, citing Chamberlain, in his new Viet Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present (in a section of the first chapter entitled “Tai and Vietics in Prehistoric Việt Nam”).

To quote, Kiernan cites undocumented “remarks” that esteemed Vietnamese linguist (but not a linguist of Tai linguistics), Nguyễn Quang Hồng made at a Nom Studies Workshop at Yale University in 2008 to state that “The date of the Vietics’ arrival in the north is disputed. Some linguists argue that Vietic speakers supplanted Tai speakers in the Red River Delta as early as the second millennium BCE.”

He then cites Chamberlain’s article to say that “One [linguist] suggests a date in the first millennium CE.”

Kiernan then offers his own opinion that “The truth may lie somewhere between.” (46)

If, however, we follow the work of linguists who actually specialize on Tai linguistics (and who do not make unsubstantiated historical claims like Chamberlain did), we will find that none of the above statements are accurate.

Linguists who focus on Tai languages do not see evidence of Tai languages as early as Nguyễn Quang Hồng’s claim (if in fact that is actually what he said). At most they talk about a proto-Tai language 2,000 years ago (Wei, Hartmann, Wang, et. al., “GIS in Comparative-Historical Linguistics Research: Tai Languages”), or 1,500 years ago (Anthony Diller, “The Tai Language Family and the Comparative Method”), while, as stated above, Tai linguists see the spread of Southwestern Tai languages into the mountains of northern Vietnam and into Laos and Thailand only starting to take place around the eighth and ninth centuries CE.

In other words, the scholarship of linguists who focus on Tai linguistics argues that Tai-language speakers arrived on the periphery of the Red River Delta right about the time that Chamberlain argued that they were “replaced” by Vietnamese speakers. . .

My own limited research of this topic has pointed to the same conclusion (see here and here).

This, of course, does not rule out the possibility that some earlier Tai-language speakers had migrated southward, but the large-scale migrations that led to the spread of Southwestern Tai languages, and that led to some cultural interactions between Tai-speakers and Vietnamese-speakers) did not start to occur until the end of the first millennium CE.

This Post Has 5 Comments

But he has recently published another paper named ”Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam” in which he claims that the northern Vietnam was occupied by the Hlai prior to the Northern Tai like Saek, Nyo, etc, and that Northern Tai branch is in fact completely separated from the Central and Southwestern branches. Moreover, he also mentions your work in his paper.

What do you think about it?

I haven’t read it. I will check it out. Thanks for pointing it out to me!!

Yes, this is a reason why I pointed out that there are a lot of proto-Hlai word in Vietnamese.

Oh, no, this article definitely doesn’t work for me. The paragraph below is an example of what doesn’t work.

Chamberlain cannot read Chinese texts, so he relies on what other people have said about them, everyone from Aurousseau to people today. In so doing, he has no way to determine what information is accurate and what isn’t.

For instance, in the paragraph below he mentions that Gu Yewang stated that Jiaozhi was known as the country of the Luo Yue [Lac Viet] during the Zhou Dynasty period. Gu Yewang wrote in the 6th century AD. There is no information before that time which says that during the Zhou, Jiaozhi was known as the country of the Luo Yue. So how did Gu Yewang know this?

What becomes very clear when you read Chinese texts and their annotations, is that Chinese scholars tried to “rationalize” and “systematize” the chaotic information that they found in earlier sources. So we can’t use a statement like Gu Yewang’s in the 6th century AD to learn something about the Zhou Dynasty period.

I can see problems like this occurring repeatedly in this article.

That’s why I like what Brindley has written. She can read the sources, and she doesn’t produce a clear narrative of “what actually happened,” because the sources do not make that possible. Aurousseau tried and failed at it, and everyone else who has made the same effort has failed as well.

The sources are simply too vague and problematic. Just because a Chinese author referred to someone as Yue or Li does not mean that we can clearly connect that name to a certain group of people. There are too many contradictions in the sources to allow that.

Finally, the fact that there are no citations here and Chamberlain is mixing together different forms of Romanization also makes this article article pretty chaotic. This topic requires much more precision than Chamberlain is bringing to it here.

Here’s the sample paragraph I’m talking about:

The fi rst mention of the Ou in Chinese, according to Aurousseau, is in the Houainan tseu (Huainanzi) supposedly composed in 135 BCE. This source states that sometime between the years 221 and 214 BCE, the reign of Qin Shi Huang, Chinese troops conquered the Yue country and killed Yi Hiu Song a feudal lord of the Si Ngeou [western Ou], said to designate the people of Tonkin at that time. Earlier, though perhaps less certain, is a text by Sima-Qian in the 1st century BCE, apparently citing an older text dating from the 3rd century BCE, referring to Ngeou-Yue people who stereotypically, “cut the hair, tattoo the body, cross the arms and fasten the clothing on the left.” A later text, the Yu-ti tche, attributed to Kou Ye Wang dating from 510-581 CE, states that Jiaozhi was known as the country of the Lo-Yue in the period of Zhou, and under the Qin was called Western Ou (ibid). This implies that the term Lo predates Ou in this southern portion of Yue.

Maybe you should write a peer review on his paper.

Do you think that a Hlai presence in northern Vietnam rather than Austronesian is plausible ?