One very interesting aspect about what historians have labeled “the Vietnamese annexation of Cambodia” in the 1830s is that from the perspective of the values that a lot of us uphold today one can see both “bad” and “good” elements in this period.

On the one hand, Nguyễn Dynasty emperor Minh Mạng did indeed have a long-term goal of incorporating Cambodia into his empire, and today we see such an effort to take over the sovereignty of another country/kingdom as “bad.”

On the other hand, Ming Mạng also ordered the implementation of certain policies that we value today, such as eliminating excessive taxes, establishing a government based on the concept of meritocracy rather than nepotism, and banning opium and gambling. In other words, some of the things that Minh Mạng wanted accomplished in Cambodia were things that we would today consider “good.”

Let us take a look at the issue of opium and gambling.

In 1838, Minh Mạng banned opium and gambling in Cambodia. Opium and gambling were illegal in the Nguyễn empire, and when Minh Mạng learned that they existed in Cambodia, he ordered that Nguyễn laws be followed there and that opium and gambling be banned.

There was one complication though: the person who was the nominal head of Cambodia at that time, Ang Mei (whom the Nguyễn referred to as “Commandery Lord Ngọc Vân”), personally benefited from the sale of opium and the operation of gambling dens.

So in seeking to ban opium and gambling, Minh Mạng also had to find a way to appease Ang Mei.

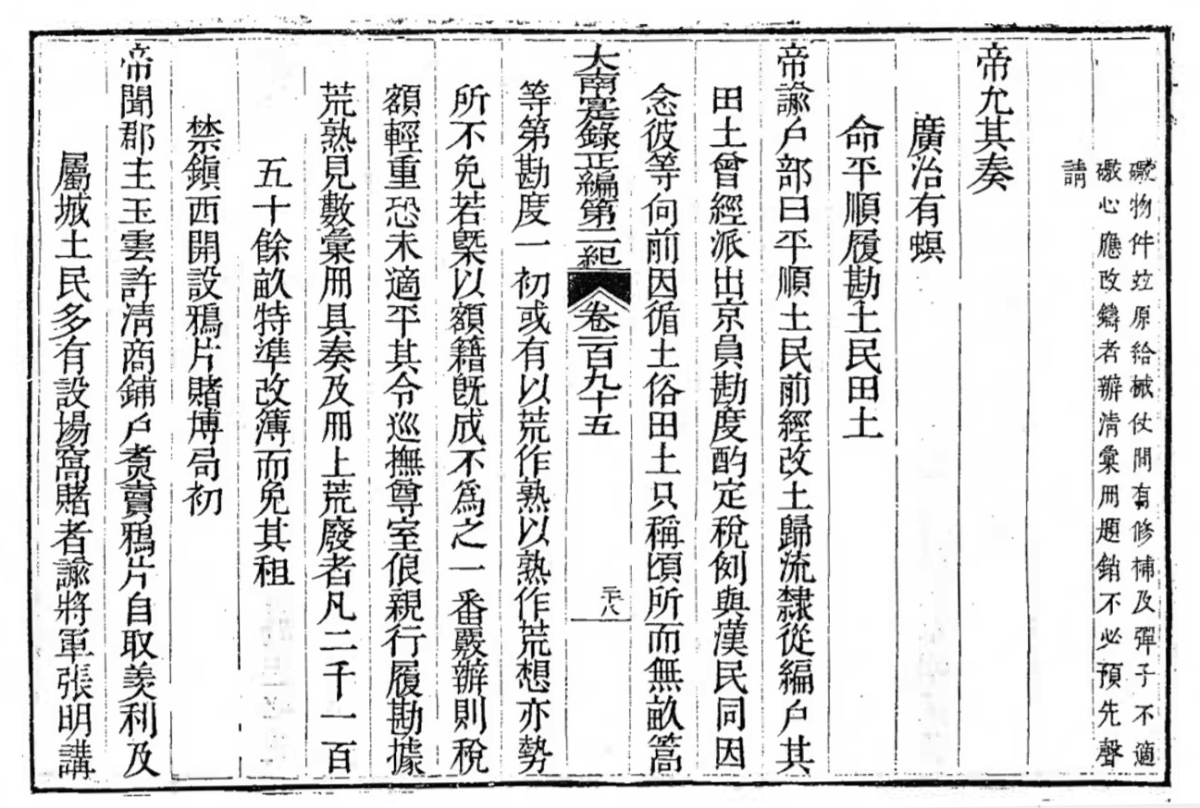

This is what the Đại Nam thực lục records about this matter:

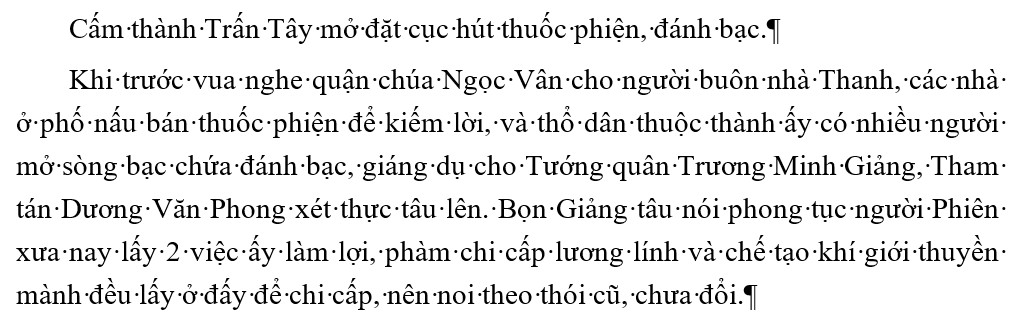

“When the emperor learned that Commandery Lord Ngọc Vân [i.e., Ang Mei] had allowed the street shops of Qing merchants to prepare and sell opium so that she could profit, and that many of the local people in the city had opened gambling dens, he ordered General Trương Minh Giảng and Grand Adjutant Dương Văn Phong to investigate the matter and submit a report.

“Giảng, et al., reported that the Phiên [i.e., “Cambodian”] custom has been to make profits from these two [businesses]. Each expediture for military provisions and the manufacture of weapons and ships is taken from this [source], and therefore it continues to be followed and has not been eliminated.”

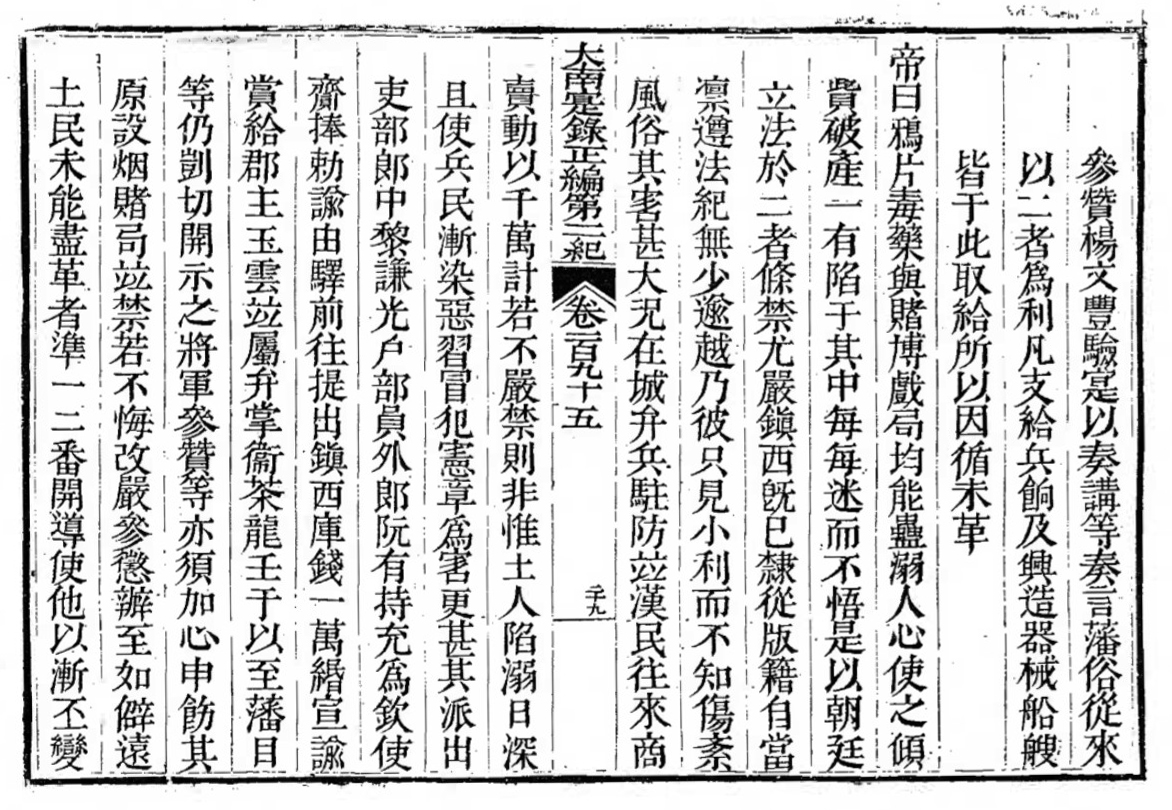

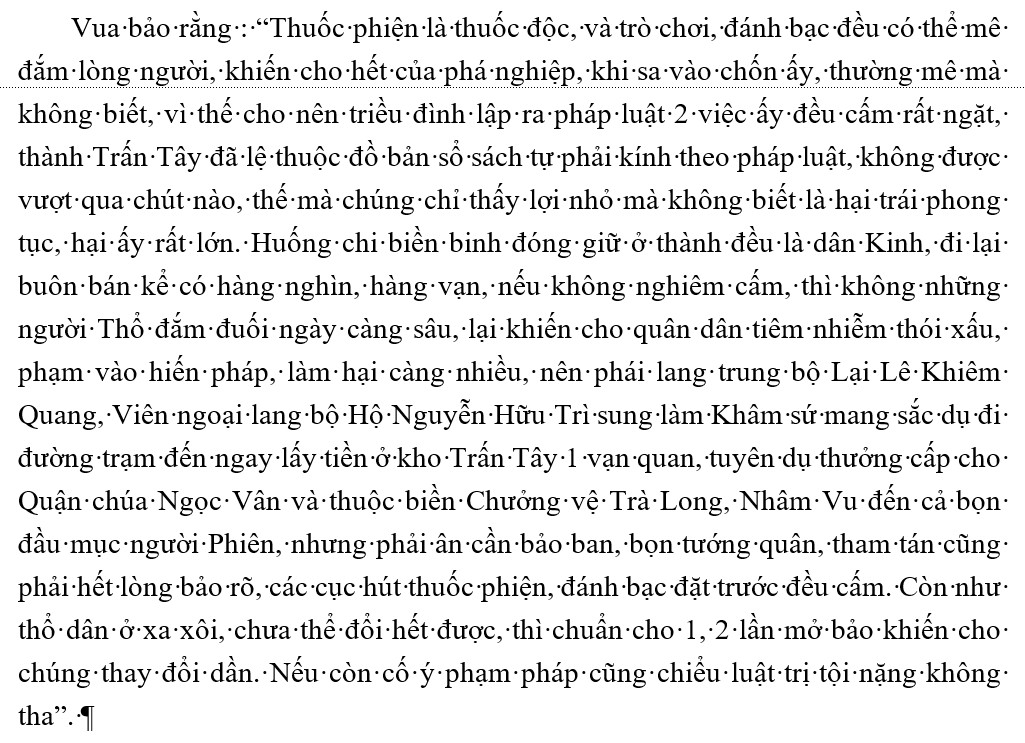

Emperor Minh Mạng responded that, “Opium and gambling can both entrance people, leading them to lose all of their wealth. Each person who falls into their trap becomes infatuated and cannot come to his senses. For this reason, the court established laws concerning both and strictly prohibits them.

“Trấn Tây [i.e., “Cambodia”] has been incorporated into [our administrative] registers, and must follow the law without the slightest transgression. They only understand about small profits and do not understand how harmful damaging customs are.

“What is more, the soldiers and clerks defending the citadel and the Hán [i.e., “Vietnamese”] merchants visiting there number in the thousands. If this is not prohibited, not only will the local people become ever more addicted, but soldiers and [Hán] people will become infected by these evil habits and will violate the laws, leading to ever more serious harm.” (195/28b-29a)

Minh Mạng then ordered that opium and gambling be banned, but at the same time he also ordered that money from the Nguyễn Dynasty’s treasury in Cambodia be granted to Ang Mei and various Cambodian military officials. That money, meanwhile, did not come from Cambodia, as the Nguyễn did not have a tax system in Cambodia. It came from the Nguyễn Dynasty’s central treasury. (195/29a-29b)

In other words, Minh Mạng wanted to replace a system where the Cambodian elite were relying on income from opium and gambling to one in which they received funds from the central state.

He wanted to this because he believed that opium and gambling were both evil and inflicted great harm on society.

One has to wonder, however, what Ang Mei thought of this. Was she ok with one of her sources of revenue getting taken away? Did she receive as much money from the Nguyễn as she had received from opium and gambling? Did she understand the moral point that opium and gambling destroyed lives? If so, why had she approved of a system that allowed this to happen?

In his A History of Cambodia, historian David Chandler points out this fact that the Nguyễn Dynasty tried to implement some changes in Cambodia that were beneficial. As he notes, however, some of these same changes were resisted by some members of the political elite, or oknha.

Chandler notes the complexity of such a situation when he states that,

“It is significant that the okya [oknha]. . . could easily rally followers to defend the status quo rather than what might have been a more equitable and forward-looking Vietnamese administration. There are interesting parallels here, moreover, with the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) administration in the 1980s.” (128 in 1st ed.; 155 in 4th ed.)

There are indeed parallels between the 1830s and the 1980s in Cambodia, but many other societies around the world have had similar experiences as well.