In 1834, Vietnamese and Cambodian forces succeeded together in driving the Siamese out of Cambodia, and King Chan, who had fled to Vietnam (see this post) was able to return to Phnom Penh.

In his A History of Cambodia, historian David Chandler writes that “When Chan returned to his battered, abandoned capital in early 1834, he found himself under more stringent Vietnamese control. Thai successes in their overland offences had shown Minh Mạng that he could not rely on the Khmer to provide a ‘fence’ for his southern and western borders. With the defeat of the rebellion, he now moved to intensify and consolidate his control.” (123-24 1st ed.; 149-50 4th ed.)

The term “fence” that Chandler refers to here is a Chinese term that the Vietnamese used in referring to the king of Cambodia and his officials – phiên 藩. This term literally means “fence” but it is a term that the Chinese had long used to refer to “border” areas that were ruled over by people who were ethnically different and deemed to be inferior (“barbarians”) but who were serving the Chinese court as “vassals” and as people who protected the frontier of the Chinese world by serving as a kind of “fence.” The Vietnamese followed this usage of this term.

This term therefore combines together various concepts: fence, border, barbarian and vassal. It is difficult to find a single English term that can capture all of those meanings. That said, I think the term “outpost” is acceptable (“outpost king,” “outpost officials,” etc.), as it denotes a place far from a political center, and from “civilization,” which serves a particular defensive purpose.

In any case, according to Chandler, during the war with Siam emperor Minh Mạng came to believe “that he could not rely on the Khmer to provide a ‘fence’ for his southern and western borders” and that after the war “he now moved to intensify and consolidate his control” and as a result “found himself under more stringent Vietnamese control.”

These statements are partially true, but there is a significant inaccuracy. The problem is with the term “the Khmer.” During the war, Minh Mạng did not come to believe that he could not rely on “the Khmer.” Instead, he came to conclude that he could only rely on “some Khmer,” namely those who were fighting against the Siamese.

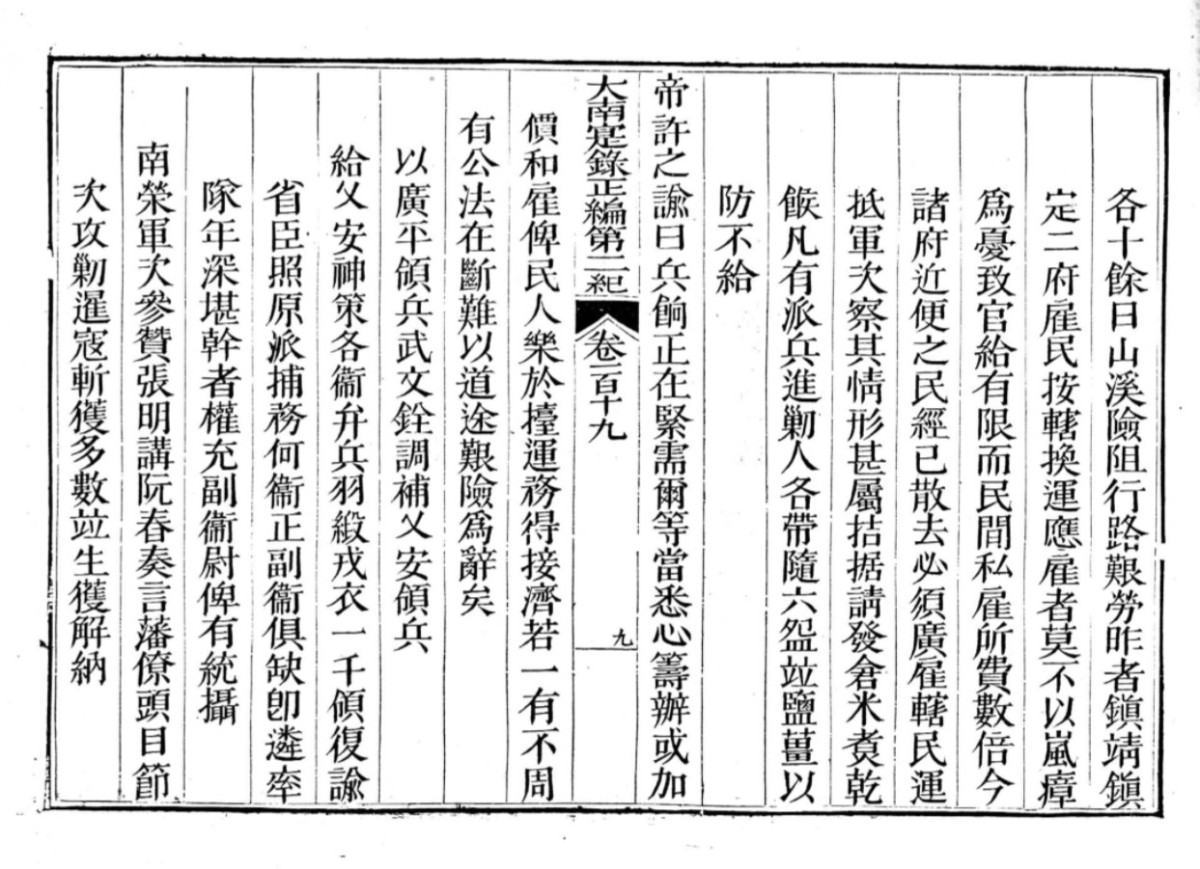

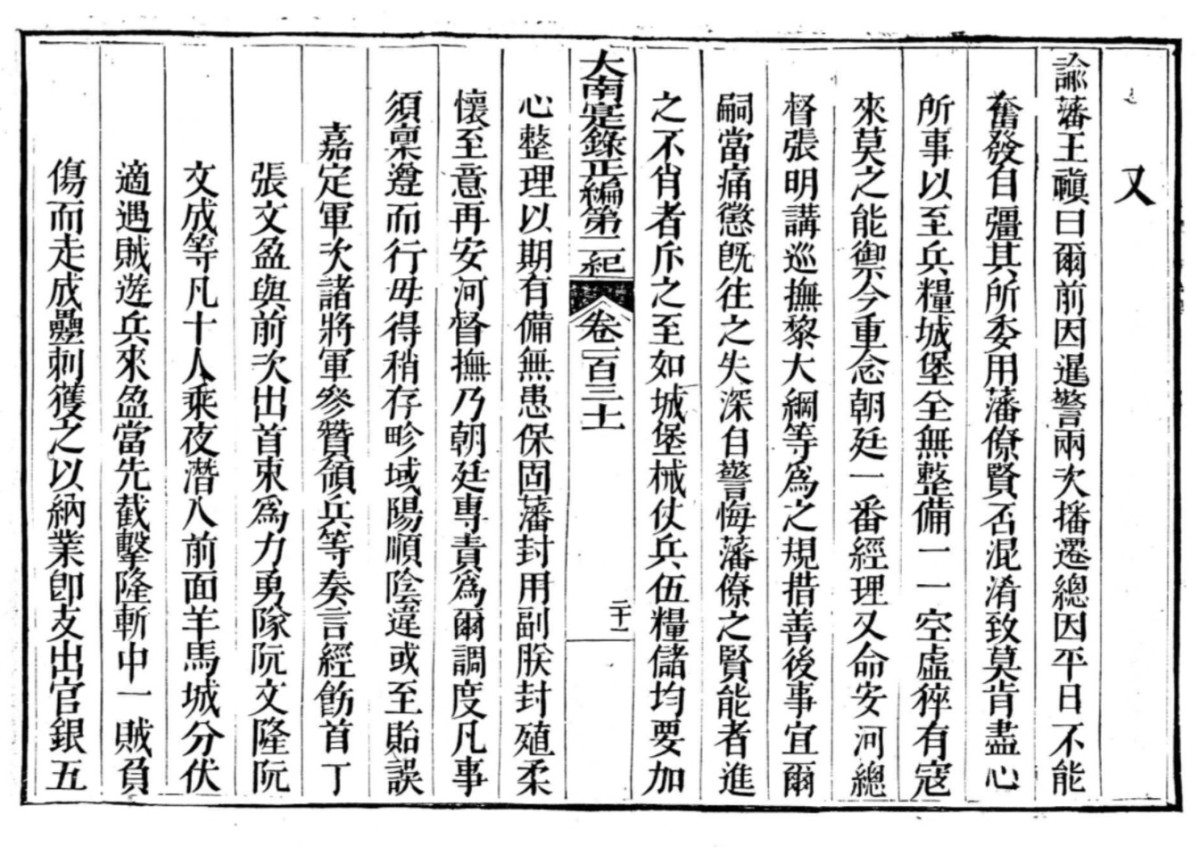

In 1834, while the war was still underway, Vietnamese officials Trương Minh Giảng and Nguyễn Xuân reported to Emperor Minh Mạng that “The outpost officials and leaders have repeatedly routed the Siamese bandits, decapitating many of the captured but also handing over [to us] those they captured alive.” (119/9b)

Minh Mạng then responded to this report by stating that,

“When the Siamese came to pillage, the Outpost king [Phiên vương 藩王] ran away but Outpost officials [Phiên lieu 藩僚] and others who possessed hatred for the enemy collected people together and captured many Siamese bandits. This is truly worthy of reward! I approve the dispersal of 2,000 in cash to grant the leaders and the troops as an encouragement.

“As for those leaders who have meritorious achievements, depending on rank, give each one a robe made of either satin brocade, silk crepe or silk gauze; also give them flying dragon silver coins and read the decree to encourage them.”

Minh Mạng also wanted the names of such meritorious officers to be recorded, as well as their achievements, so that later they could be granted official positions. (119/10a)

So contrary to what Chandler wrote, Minh Mạng did recognize that some Cambodians could be relied upon. However, King Chan was not one of those people, nor were the 1,800 officials and followers who fled with him to Vĩnh Long Province in southern Vietnam in late 1833 or early 1844.

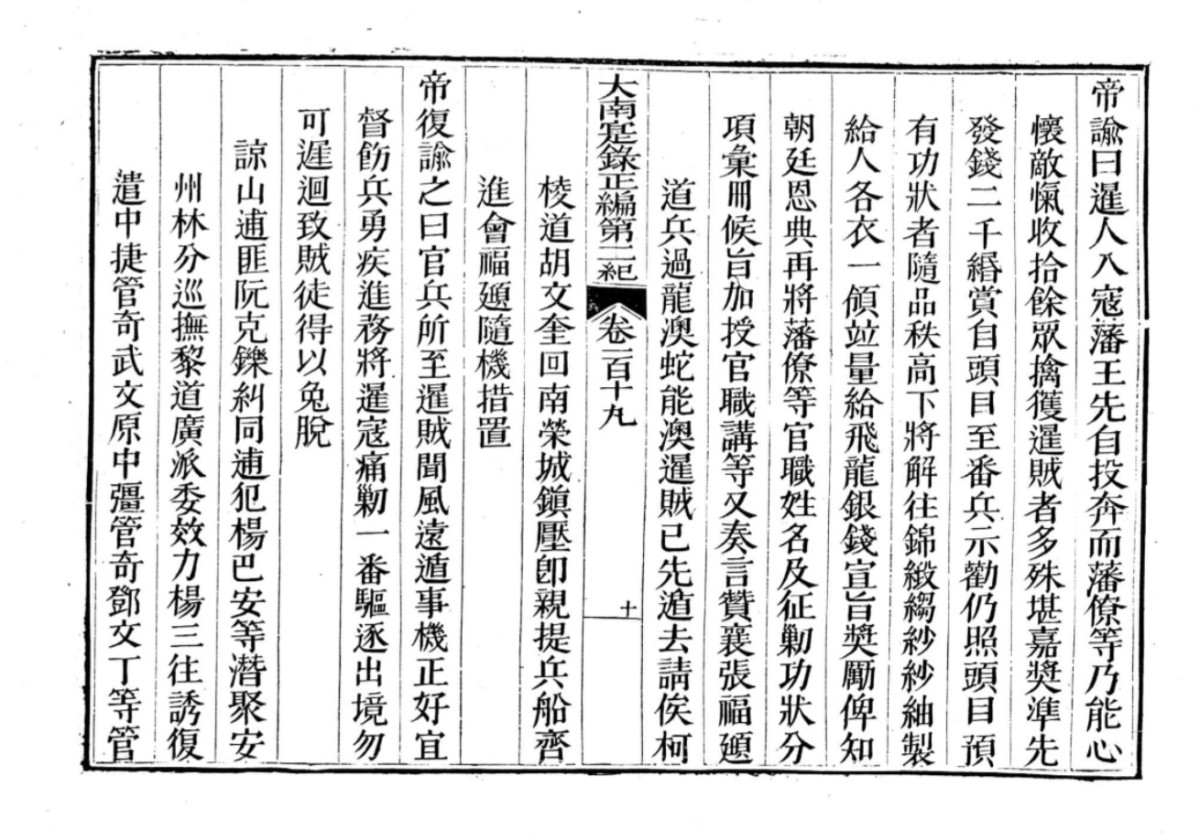

We can see this clearly in a decree that Minh Mạng sent to King Chan in 1834 when the war had ended. Minh Mạng chastised King Chan for having been negligent and demanded that he reform his kingdom so that it could protect itself. This included promoting “worthy” officials and firing “unworthy” officials.

This is what he wrote:

“Previously on two occassions you ran away because of the Siamese threat. This is because you did not make regular efforts to strengthen [the kingdom] yourself. You employed such a confused mixture of worthy and unworthy outpost officials that none were willing to fully exert themselves in carrying out affairs. This led to provisions for troops and fortresses being left completely unprepared and unattended. So when the bandits arrived, no one could resist them.

“I solemnly hold that the [Nguyễn Dynasty] court must rectify this situation, and have ordered that Governor-general of An Giang and Hà Tiên Trương Minh Giảng and Governor Lê Đại Cương to put affairs in order for you so that this does not happen again.

“From this point onward you must strongly warn against the mistakes of the past, and you yourself must feel a deep sense of alarm and regret. Promote the worthy outpost officials and dismiss the unworthy ones.” (131/21a)

Ming Mạng then went on to mention some specific measures that he demanded the king take in order to ensure that the kingdom was militarily prepared to defend itself.

In other words, contrary to what Chandler wrote, Minh Mạng did not exactly want to intensify and consolidate “his” control. Instead, he wanted certain Cambodians to intensify and consolidate “their” control, and the purpose of this was so that they would indeed “provide a ‘fence’ for his southern and western borders.”

Finally, and also in contrast to what Chandler wrote, Ming Mạng believed that there were Cambodians whom he could rely on to do this – the “worthy” ones. And who were these worthy Cambodians? They were the ones who had fought against the Siamese.

Does this mean that after the war ended King Chan “found himself under more stringent Vietnamese control”? Kind of. However, I think it is more accurate to say that King Chan found himself under severe Vietnamese pressure rather than control, and that he also found himself under a lot of Cambodian pressure too.

Ming Mạng ordered the king to reorder the power structure in Cambodia. Any time there is a reordering of a power structure, some people gain and some people lose.

Minh Mạng ordered King Chan to undertake such a reordering of the power structure in Cambodia, and King Chan and some of his closest associates were going to be among those who were set to lose in this restructuring, as they had not fought the Siamese.

That was indeed a lot of pressure to be under. This is because this pressure came from multiple directions.

First, it obviously came from the Vietnamese court, as Minh Mạng wanted to see the power structure in Cambodia reordered.

Second, it also must have come from the various powerful officials in Cambodia who wanted to keep their positions of power, even though they were “unworthy” according to the stipulations that Minh Mạng had laid out since they had not fought against the Siamese.

Third, there was also likely pressure from the people who were deemed as “worthy” by the Vietnamese, as they were set to gain positions of power that they had previously not enjoyed and which they believed that they deserved for having fought the Siamese.

King Chan was indeed under a lot of pressure.

This Post Has 4 Comments

What about the term “buffer” in place of “outpost,” since Minh Mạng intention was to maintain the Cambodian Kingdom as a buffer state?

Yea, “buffer” is better than “fence.” But I’m trying to find a term that gives a sense of the “inferiority” of the place from the perspective of the court. An expression like “barbarian buffer” might work best. I need to think some more about this, but thanks for the suggestion!! 🙂

_ in Europe , there was as outpost the ” marche ” which later gave rise to the title ” marquis ”

I think there were 2 kinds of Phiên 藩(=vassals) : Han ones and barbarian ones 外 ngoại 藩 Phiên

_ here is a synopsis of the various levels of imperial chinese administrative influence

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinocentrism#/media/File:Tenka_Qing.png

_ the western part of Cambodia was once annexed to VN and named 鎭 Trấn 西 Tây 城 Thành

_ Kampuchea was phonetically transcripted to Kan (柬 giản) pou (鋪 phô) jia (寨 trại)

_ nowadays Chinese call Pnom penh as Kim 金 biên 邊; it’s perhaps a transcription of Cam – bodia ; maybe that’s why one mentions the khmer king as ” border king ”

_ Chan is a frequent name of Khmer kings ; in full , in Vietnamese , it’ s Nặc 諾 ông Chân or Norodom

I was thought of “matches,” but since it is a military administrative unit inside the border of a nation then it would not be the right fit. I think the Tang Dynasty had a designation similar to a marches; quân (軍), which was what they called their military administration on he frontier–e.g. Tĩnh Hải Quân (靜海軍).