The history of the relations between Cambodia and Vietnam is long and complex, and there are various elements of that history that make people today unhappy or angry when they think about them.

What common people think about the past, however, is not always the same as what historians can see and document about the past. As such, one important role that professional historians play is to try to explain what happened in the past as accurately as possible so that people can base their ideas about the past on an accurate understanding of what actually happened in the past.

That said, there is an issue from the history of Cambodia-Vietnam relations that makes Cambodians very angry that historians have not done a good job of explaining accurately, and that is the idea that during the time of Nguyễn Dynasty emperor Minh Mạng’s reign (1820-1841), Cambodians were forced to change their hairstyle and the way they dressed.

In his A History of Cambodia, historian David Chandler writes about such “cultural reforms,” and explains that “One of these was the order that Khmer put on trousers instead of skirts and wear hair long rather than en brosse.” (en brosse = cut short)

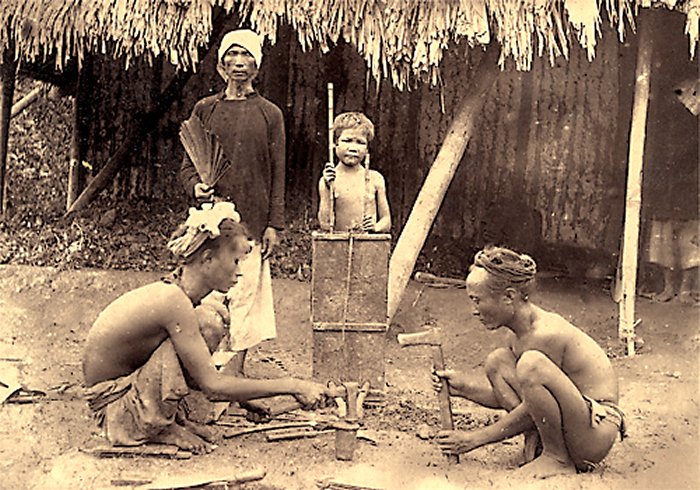

Chandlers notes further that, “Other ‘barbarous’ Cambodian customs, according to a Vietnamese writer, including wearing robes without slits up the sides, using loincloths, eating with fingers, and greeting from a kneeling position rather than from an upright one.” (126-7 1st ed.; 153 4th ed.)

Chandler does not cite any evidence to support his claim that there was an “order that Khmer put on trousers instead of skirts and wear hair long rather than en brosse.”

Let me repeat that: Chandler does not cite any evidence to support his claim that there was an “order that Khmer put on trousers instead of skirts and wear hair long rather than en brosse.”

As for the reference to “other ‘barbarous’ Cambodian customs,” that reference comes from a different time and context than the time of the Vietnamese annexation of Cambodia in the 1830s. Chandler’s understanding of that reference is inaccurate because he relies on a poor translation: Gabriel Aubaret’s 1867 translation of Trịnh Hoài Đức’s Gia Định thành thông chí (嘉定城通志; Comprehensive Gazetteer of Gia Định Citadel).

Aubaret himself, meanwhile, made some assumptions about a passage in this text which probably has contributed to the idea that the Vietnamese tried to transform Cambodian customs in the nineteenth century.

Let us look at what Trịnh Hoài Đức wrote and what Aubaret wrote.

Trịnh Hoài Đức (1765-1825) was an extremely erudite Nguyễn Dynasty official of Chinese descent. He supposedly presented his Gia Định thành thông chí to Emperor Minh Mạng when he came to power in 1820.

The year 1820 was 14 years before “the Vietnamese annexation of Cambodia” began, the time when, if we believe Chandler, some order was given “that Khmer put on trousers instead of skirts and wear hair long rather than en brosse.”

So what exactly is it that Trịnh Hoài Đức wrote at some point before 1820?

Trịnh Hoài Đức has a section in the Gia Định thành thông chí in which he writes about the history, up to his time, of the relations between the Cambodian and Vietnamese kingdoms.

In 1806 a new king came to power in Cambodia, King Chan (the same King Chan that was in power in the 1830s). He was backed by the Siamese, but he had two brothers that the Siamese liked as well.

Perhaps in an effort to solidify his hold on power, King Chan requested to become a vassal of the Nguyễn Dynasty (at the same time that he was also essentially a vassal of Siam), and was confirmed that status in a ceremony that was held in 1807.

From that point onward, when the king and his officials met with Nguyễn Dynasty officials, they would take part in ceremonies that followed Nguyễn Dynasty protocols.

This is what Trịnh Hoài Đức’s remarks made reference to. Let us look at what he wrote.

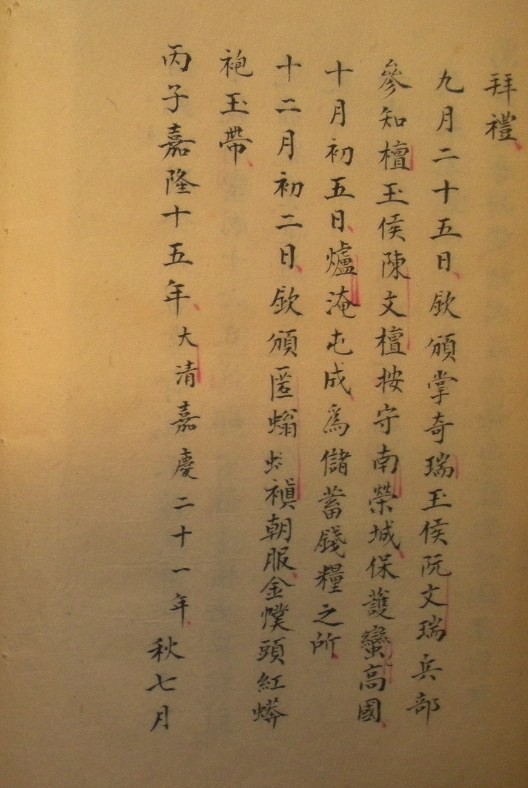

In remarking on one ceremonial occasion in 1816, Trịnh Hoài Đức notes that King Chan was given special robes by the Nguyễn court and then he states that:

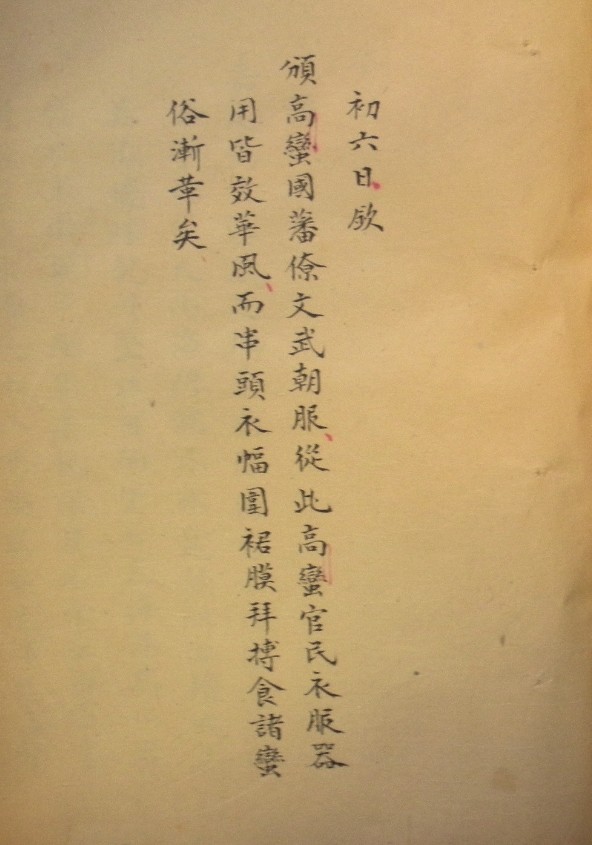

“In the autumn, on the sixth day of the seventh lunar month, the Cao Man [i.e., ‘Cambodian’] civil and military officials were granted court robes.

“From this point onward the Cao Man officials and people all emulated the Hoa style in their clothing and utensils, and savage customs such as wearing pull-over tops and wrap-around skirts, prostrating on the ground, and eating by grabbing [with their fingers] started to gradually be eradicated.”

秋七月初六日,欽頒高蠻國藩僚文武朝服。從此高蠻官民衣服器用皆效華風,而串頭衣、幅圍裙、膜拜、搏食諸蠻俗漸革矣。

Let us now analyze this passage and see what it means.

First of all, Trịnh Hoài Đức saw a distinction between “savage” (man 蠻) ways and “Hoa” (華) ways.

What was the “Hoa style” (Hoa phong 華風) that Trịnh Hoài Đức mentioned? It was to be like a Nguyễn Dynasty official, that is, to wear certain kinds of robes; to read and write in classical Chinese; to follow certain ritual practices that were recorded in antiquity, etc.

In other words, what was important to Trịnh Hoài Đức were the same things that were important to members of the Chinese and Korean elite at that time as well. These were universal practices that the educated across East Asia thought everyone should follow.

Did that mean that members of the educated elite forced everyone in their kingdoms/empires to dress like them and to learn classical Chinese? No. There were millions upon millions of people across East Asia at that time who did not follow the “Hoa style,” and the ruling elite didn’t care.

The elite did care, however, about matters at their elite level, and this included the extremely important world of tributary politics. When Vietnamese and Korean envoys visited Beijing on tributary missions, for instance, they wore “Hoa” robes and performed the proper “Hoa” rituals at the court.

Similarly, when Qing Dynasty envoys visited Vietnam or Korea, they were welcomed in rituals where everyone wore “Hoa” robes and performed the proper “Hoa” rituals.

In its relations with Cambodia, the Nguyễn Dynasty tried to replicate the kind of protocol that existed in its own tributary relationship with China.

Was this forced? Theoretically it was not supposed to be, as the fact that people outside of a kingdom wore the same robes and knew the same rituals was supposed to be a sign of the incredible power and attraction of the “Hoa style.”

In this way, elite ideas about clothing and rituals in the premodern East Asian cultural tradition were a lot like ideas about Christianity among Westerners at that time.

The supposed inherent power and goodness of the religion was supposed to naturally attract new converts, and the more converts that came, the more this “truth” was demonstrated.

Trịnh Hoái Đức’s claim [at some point before 1820] that “From this point [1816] onward the Cao Man officials and people all emulated the Hoa style in their clothing and utensils”. . . shares a lot with the kind of statements that Christian missionaries made at that time that say things like “hundreds of pagans came to be converted,” etc.

Were these statements actually true? Only partially. Instead of “hundreds” came to be converted, we usually understand such statements from 19th-century missionaries to mean “we managed to convert [we think] some people.”

And instead of “From this point onward the Cao Man officials and people started to emulate the Hoa style in their clothing and utensils”. . . we can understand this to mean that “at court ceremonies held in Phnom Penh for visiting Nguyễn Dynasty officials, the Cambodian officials dress in ‘Hoa’ robes and use chopsticks at the banquet that follows the ceremony.”

In other words, statements like these were exaggerations, and they were made to impress someone important. Missionaries made such statements in reports to church officials back in Europe, and Trịnh Hoái Đức made his statement in a text that he presented to a new emperor, Emperor Minh Mạng, in 1820.

In 1867, a French officer by the name of Gabriel Aubaret translated Trịnh Hoài Đức’s Gia Định thành thông chí. However, Aubaret’s knowledge of Chinese was not good enough to translate this work correctly, particularly since he also lacked the cultural and historical background knowledge that is necessary for translating this text.

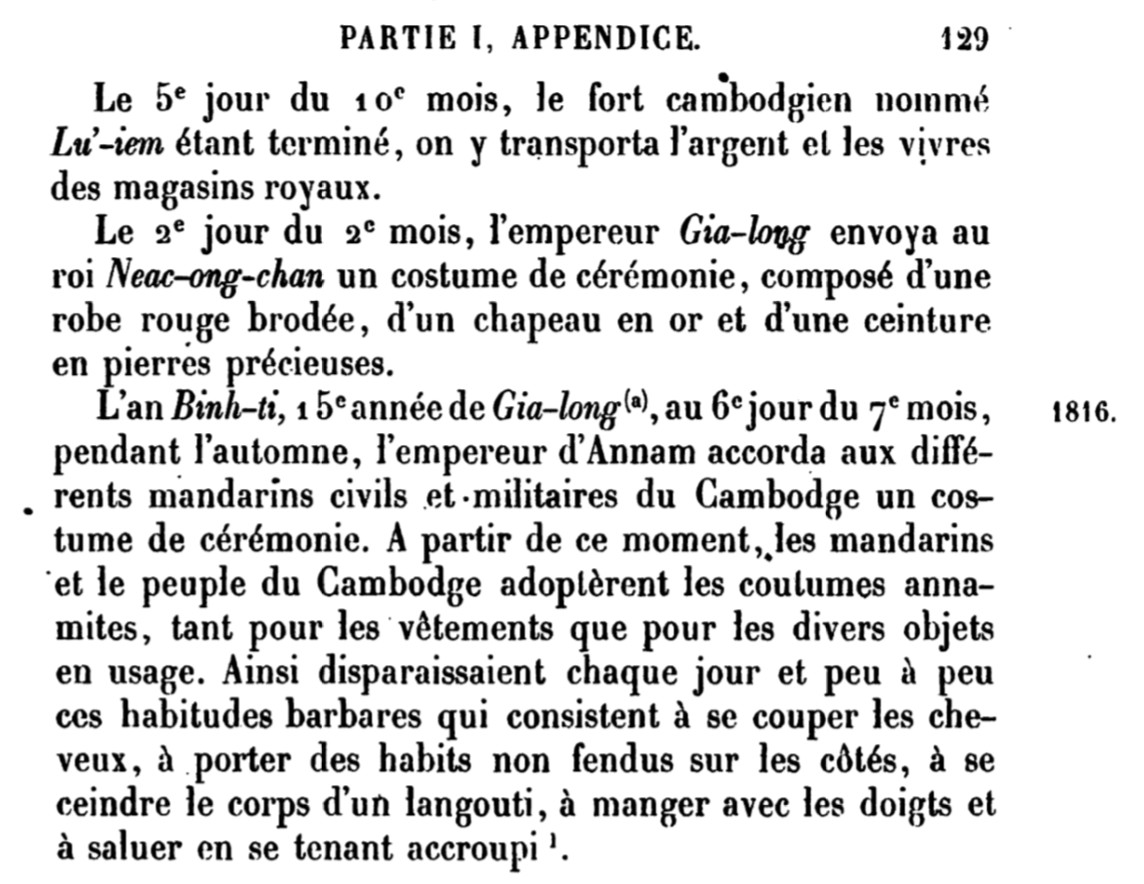

If we translate his French translation into English, we end up with something like this:

“In the year Binh-ti, 15th year of Gia-long, on the 6th day of the 7th month, in the autumn, the emperor of Annam granted the various civil and military mandarins of Cambodia a ceremonial costume. From then on, the mandarins and the people of Cambodia adopted Annamese customs, both in terms of clothing and objects of use. Thus, every day, little by little, the barbarous habits of cutting off hair, wearing clothes not split on the sides, girding the body with a loincloth, eating with fingers and greeting while squatting disappeared.”

Out of the four habits that Trịnh Hoài Đức claimed were gradually changing, Aubaret only got one of them correct: eating with fingers.

Trịnh Hoài Đức did not say anything about cutting off hair. He said that they wore pull-over tops (串[=貫]頭衣), a very common marker of being a “barbarian” in the East Asian cultural tradition.

Trịnh Hoài Đức also did not say anything about “wearing robes without slits up the sides, using loincloths,” etc. Instead, he noted that the Cambodians wore lower-garments that consisted of a single piece of cloth that they wrapped around their bodies.

And finally, Trịnh Hoài Đức did not say that they had a practice of “greeting from a kneeling position rather than from an upright one.” He said that they prostrated themselves on the ground.

So Aubaret did not understand some of what Trịnh Hoái Đức actually wrote (and Chandler repeated his misunderstandings). At the same time, he appears to have literally believed Trịnh Hoái Đức that all of these customs were changing among the entire Cambodian population, as Aubaret made the following statement in a footnote on that page:

“The Cambodians have, in our day [meaning the 1860s], resumed all their national customs. Only those who live in Annamite territory, to be exact, have a costume that is sometimes, though rarely, similar to that of [the people of] Annam. However, women only cut their hair in the kingdom of Cambodia; they wear it long among the Annamites, but their hairstyle is a little different from that of the women of Cochinchina.”

David Chandler does not cite any evidence to support his claim that there was an “order that Khmer put on trousers instead of skirts and wear hair long rather than en brosse.” He only misquotes (through Aubaret’s bad translation) some statements that Trịnh Hoài Đức had earlier made in a different context.

Trịnh Hoài Đức’s did make some comments about clothing, but he did not say that there was an “order that Khmer put on trousers instead of skirts and wear hair long rather than en brosse.”

Instead Trịnh Hoài Đức recorded that military and civil officials at the Cambodian court in 1816 wore “Hoa” robes when they participated in rituals that were part of the suzerain-vassal relationship with the Nguyễn Dynasty.

This is something that Cambodian officials continued to do in the years that followed.

As for the other changes that Trịnh Hoài Đức claimed were taking place day by day. . . Those need to be put in context.

Trịnh Hoài Đức’s text was presented to the emperor in 1820. . . Did the power of the Hoa-style robes that the Nguyễn court granted Cambodian officials in 1816 suddenly transform the entire kingdom of Cambodia and lead every peasant to rush to find a way to purchase such robes so that they could partake in the transformative power of the Hoa way?

That’s the kind of premodern propaganda that someone like Trinh Hoài Đức would have wanted his new emperor to believe, as it made him look good, just like the way that Christian missionaries exaggerated the number of pagans they had converted so as to impress their superiors back in Europe.

In reality, “the people” had absolutely no idea what officials wore when they met with Nguyễn Dynasty representatives in the king’s palace in Phnom Penh. And Trịnh Hoài Đức did not care what “the people” in Cambodia or anywhere else wore.

He only cared about “the officials.” And as the protocol of the suzerain-vassal relationship that the Nguyễn Dynasty established with King Chan dictated, the king and his officials had to dress in the “Hoa style” when they met with Nguyễn Dynasty officials. . . and they did.

That’s the only change of dress that took place in Cambodia at that time, and there is no evidence that it was done by “order.” King Chan requested to become a vassal, after all. Wearing “Hoa” robes was part of the package.

And we can assume that when the Nguyễn Dynasty officials went away, so did the robes. That was part of the deal too.

This Post Has 3 Comments

Thank you for this Professor Kelley. As a person with both Khmer and Kinh heritages, I have felt the strain of animosity between my two people, and the subject of Vietnamese treatment of Cambodian during the Nguyễn dynasty has always been the point of contention. With that said, I can attest that some of my fellow Vietnameses still refer to my fellow Cambodians as mọi (savage) and that only reinforced the what Chandler wrote. It seem Chandler has quite a few discrepancies here, what do you think led him to make these? Was he lazy, or was there some kind of agenda? I can’t help but to think war time politics has something to do with it.

That’s a good question. I’ve been comparing what Chandler wrote in his dissertation (1973) with what he wrote in his book (1983). In the dissertation he tends to mention more complexity, and to be more critical of Khmer politics/society. In the book he simplified things, and followed more of a Khmer nationalism narrative.

The dissertation still needed more work, but instead of doing that, he went the other direction and simplified things. Why did he do that?

Yea, the timing could be one reason. He might have decided to leave out some of the more critical observations about Khmer society in his dissertation because of what the country had gone through by the 1980s.

At the same time, pretty much all of the first major books in English on the histories of Southeast Asian countries more or less followed the nationalist narratives of those countries (David Wyatt’s History of Thailand, Keith Taylor’s The Birth of Vietnam, Barbara and Leonard Andaya’s The History of Malaysia), so it might also be a reflection of that kind of time as well.

The big issue for me, however, is why Chandler never revisited this material. The issue of clothing is one that contributes a lot to the sense of hatred, and Chandler did not have evidence for that in his dissertation (I’ll write about that soon) or in his book. He must realize that, and to let that go for decades. . . that’s not good, because now that is so widely believed that it will always be “the truth” to many people. But there’s no truth in it. The only people who wore non-Khmer clothes were the Khmer officials when they met with Vietnamese officials. That is something that the Cham leaders did as well. And when the Vietnamese officials left, they could change out of those clothes and go back to wearing their own clothes.

I found that the thread that sewn South East Asia together is the Hoa communities or the Chinese diaspora, their influence is obvious in the cuisines. Just this week I had Phnom Penh noodle (hủ tiếu or kway teow) at two different restaurants, a Khmer and a Vietnamese, and both were about the same. This tells me that Han custom and culture permeated the region. So the wearing of Han official robes or carrying out Han ritual isn’t out of the ordinary, especially when the Hoa has intermarried with so many people in the region. I think S.E. Asia in the post colonial era was still caught up in nationalism, asserting their identity, and the authors you have mentioned mistaken the nationalistic narratives to be the truth and they were eager to contribute. The same goes with Vietnamese regarding China. They swear that they are truly different from the Chinese, but in my opinion they are as different the Han as Sichuan from Zhongyuan. Identity is shape by politics.