In 1744 Nguyễn Đăng Thịnh, an official in Đàng Trong, presented a letter to his ruler, Nguyễn Phúc Khoát, the “Nguyễn lord” of Đàng Trong, encouraging him to take the title of “prince.”

Only excerpts from that document remain, but as we saw in the previous post, the first two quoted lines are filled with Confucian ideas.

The same is true of the next two lines. What is more, also like the first two lines, these two lines have been inadequately translated into Vietnamese, making it impossible for a reader of the Vietnamese translation to understand their meaning.

The two lines can be translated more or less literally as follows:

“With the establishment of hegemonic intention, the yellow flag revealed itself in the southeast; With princely marks [indicating] the grand transversal, the imperial jade seal rushed to the north of the Wei.”

霸圖峙立,黃旗自表于東南, Bá đồ trĩ lập, hoàng kì tự biểu ư đông nam,

王兆大橫,玉璽已馳于渭北。 Vương triệu đại hoành, ngọc tỉ dĩ trì ư Vị bắc.

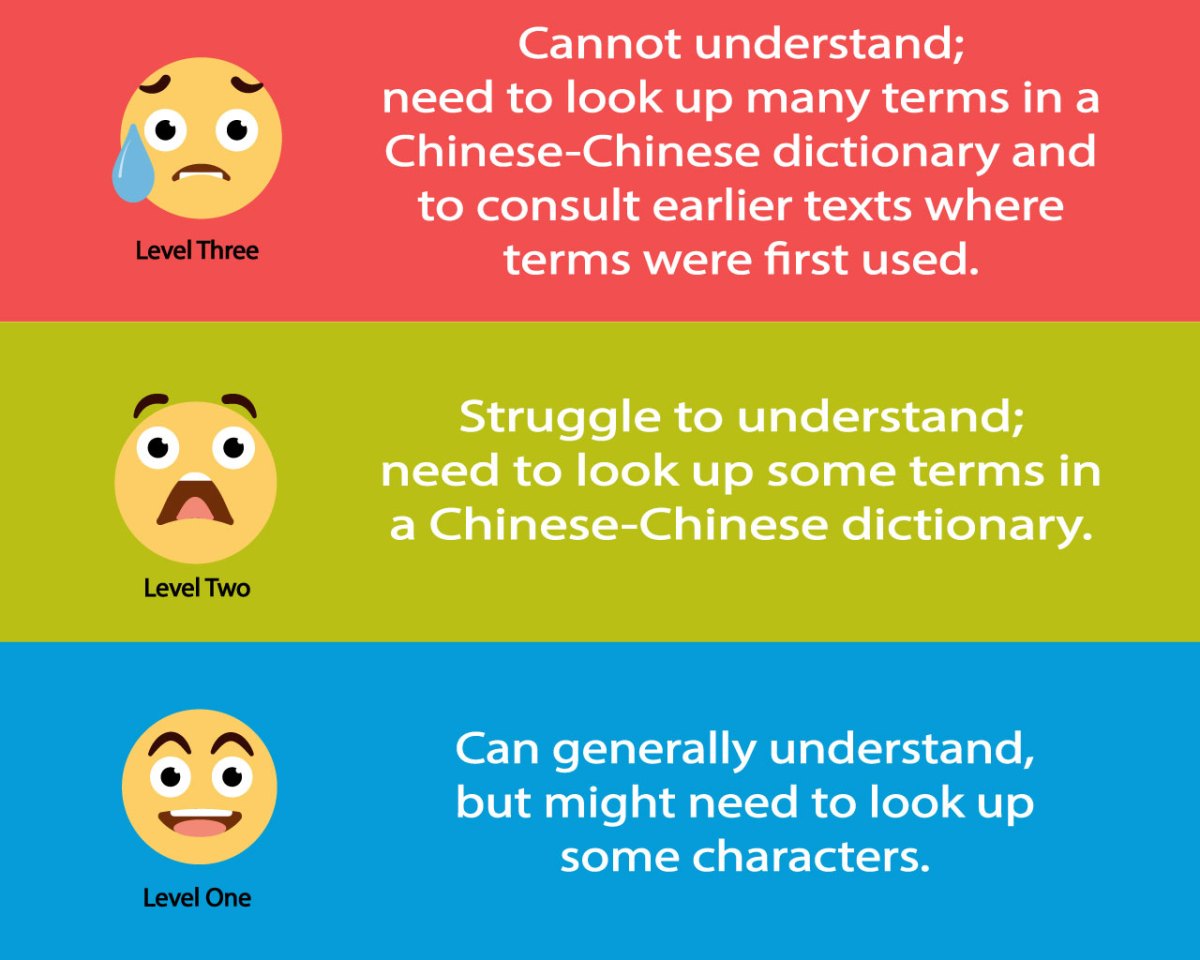

These lines fall somewhere between Level Two and Level Three of this chart. The characters used are for the most part quite common, but they are referring to some events, and it’s unclear what events those are, or who was involved in them. Therefore, understanding these lines requires that one do some research.

So how do you figure something like this out? You first look for the structure of the sentences. Sentences in classical Chinese are often written in parallel couplets, and that is true of these two sentences. Once you identify the parallel structure, you then look at the corresponding parts.

Both sentences end with a geographic term: “the southeast” (đông nam 東南) and “north of the Wei” (Vị bắc 渭北). And the second halves of both sentences begin with a term that denotes “the emperor” or “imperial power”: “the yellow flag” (hoàng kì 黃旗) and “the imperial jade seal” (ngọc tỉ 玉璽).

Between these terms in each sentence are a verb and a preposition: “revealed itself in” (tự biểu ư 自表于) and “rushed to” (dĩ trì ư 已馳于).

So it’s not all that difficult to figure out what the second halves of the sentences say:

“. . . the yellow flag revealed itself in the southeast;”

“. . . the imperial jade seal rushed to the north of the Wei.”

But what the heck does that mean?!!??

Experience tells me that anytime you see the term “bá” 霸, meaning “hegemon,” you are probably looking at a reference to Xiang Yu 項羽, one of the people who contended for power after the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) came to an end, and who was known at that time as the “bá vương” 霸王 or “hegemon king.”

However, there is also a chance that the term could be referring more generally to a time when there were multiple people contending for power, such as during the Three Kingdoms period.

So the key to deciphering these two lines lies in trying to figure out what the first four characters of the second line mean: vương triệu đại hoành 王兆大橫. I was able to do so, and with some additional historical research what I discovered is that these two sentences refer to events from the lives of the first two emperors of the Han Dynasty, Liu Bang 劉邦 and Liu Heng 劉恆.

Liu Bang was initially an official for the Qin Dynasty, and was sent to serve in “the southeast” but then turned against the Qin. Others did as well, including Xiang Yu, the “hegemon king” (bá vương 霸王) of the state of Western Chu. In the end, however, Liu Bang succeeded in defeating Xiang Yu and established the Han Dynasty, thus gaining the right to identify himself with the “yellow flag” of an emperor.

After Liu Bang died there was rivalry for control of the dynasty, and at one point his son, Liu Heng, performed turtle-shell divination in order to see if he should accept the offer to ascend the throne.

At the time, Liu Heng was serving as “prince of the state of Dai” (代王), an area located in the northern region of the empire (i.e., “north of the Wei”). The crack that appeared in the turtle shell was a “grand transversal” (大橫), which may have referred to a long horizontal line, and which was interpreted to mean that Liu Heng would become a “heavenly prince” (thiên vương 天王) (i.e., “princely marks”).

Liu Heng reportedly asked the person who interpreted the divination that given that he already was a prince, what more could this mean? The diviner stated that “heavenly prince” meant a “son of Heaven” (thiên tử 天子), that is, the emperor.[1]

Liu Heng agreed to become emperor, the only person who could use the “imperial jade seal.”

Turning to the Vietnamese translation of these two sentences, the translator(s) made a literal translation of these lines, but as my own English translation above demonstrates, just translating the words isn’t sufficient to enable a reader to understand what these two lines mean.

For that, one has to explain what they are referring to. There is no such explanation in the Vietnamese translation, and as a result, I don’t think anyone can read the Vietnamese translation and figure out what these lines are about.

It also takes quite a bit of work to figure out what the original Hán text means.

So regardless of whether an historian consults the original Hán or the Vietnamese translation, these two lines are difficult to understand (but not impossible if one works with the Hán original).

However, these two lines are very important for understanding this event in 1744 when Nguyễn Phúc Khoát became a “prince.”

Like the first two lines discussed in the previous post, these two lines are filled with imagery and ideas from the Confucian (or East Asian scholarly) tradition.

Also like the first two lines, these two lines seem to imply that Nguyễn Phúc Khoát could become someone much more powerful than a prince: he could become an emperor, like Liu Bang and Liu Heng.

[1] See Hanshu 漢書 [History of the Han], “Wendi ji” 文帝紀 [Annals of Emperor Wen], and Edward L. Shaughnessy, “Arousing Images: The Poetry of Divination and the Divination of Poetry,” in Divination and Interpretation of Signs in the Ancient World, edited by Amar Annus (Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2010), 62-63.

This Post Has 9 Comments

Thank you for taking the time to explain these sentences.

I do, however, have a question about the use of the word Vị or Wei above. My understanding is that in old Chinese style, the word type has to match in both sentences in order for them to be appropriate or correct. Thus, if in the first line, both words point to directions (đông nam), then in the second, they almost have to be the same word type of the opposite directions (tây bắc). Consequently, the word Vị, which is the name of a river tributary of the Yellow river, really should not be used in this instance!

To further illustrate, if in the first line, a place name was used and then the direction attached to it, such as Việt Nam, then in the second line, Vị Bắc would be appropriate. But that is not the case here.

Of course exceptions can always be made, as in this situation where a river’s name was used instead of a direction. But it really makes me wonder if the original text was correct, and, if so, what is the significance of the term Vị Bắc (Wei North) here, especially with respect to the imperial jade. Is there another historical meaning/story to this? How is this related to the Nguyễn who resided in the south?

Thanks for the comment. On an ideal level, yes, they should mirror each other. And in this case, I would argue that the problem is the “dong nan.” That term is too generic. “Vi bac” gives more of a sense of an historical time and place, and therefore, does a better job of alluding to something.

That said, just because something is recorded doesn’t mean that it is “good” writing, or that it has been recorded as it was originally written. We just have to go with what we have.

Winston Phan: “Consequently, the word Vị, which is the name of a river tributary of the Yellow river, really should not be used in this instance!”

The Vị/Wei river reminds me of Khương Tử Nha.

According to Wikipedia: “Khương Tử Nha (chữ Hán: 姜子牙), tên thật là Khương Thượng (姜尚), tự Tử Nha, lại có tự Thượng Phụ (尚父), là khai quốc công thần nhà Chu (…). Thủ lĩnh bộ tộc Chu là Tây Bá hầu Cơ Xương đi săn, gặp Khương Thượng đang câu cá phía bắc sông Vị. Cơ Xương nói chuyện với ông rất hài lòng, ngưỡng mộ tài năng của ông.”

Does “Vị bắc” mean “phía bắc sông Vị”? If so, then it may indeed refer to Reichsgrunder Khương Tử Nha, a reference that seems to correspond neatly with the allusion to Chu Văn vương (周文王) discussed in the preceding blog post.

Just some random associations based on years of watching Hong Kong series 🙂

Very good association, but in this case my sense is that the two halves of the sentences should be read in as “topic – comment,” and the first half of that sentence about the “grand transversal” (as far as I can tell) has to be about Liu Heng.

That said, the use of “Vi bac” could likely come from knowing this story of Khương Tử Nha even though its use here is not meant to be a direct reference to Khương Tử Nha.

So thanks for pointing that out!!

The Wei river and its valley are of utmost importance in Chinese ancient history ,

it’s the cradle of early Chinese ciivilization ; there were situated the capitals of

Chu , Tsin ( Xianyang , Hàm dương 咸陽) , Han and Tang ( Chang An ) dynasties .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wei_River#/media/File:Weirivermap.png

Another name of Xianyang was Weisheng Vị thành 渭城 , one of the most famous

Tang poems mentions Weisheng :

渭城曲-送元二使安西

渭城朝雨浥輕塵,

客舍青青柳色新。

勸君更盡一杯酒,

西出陽關無故人

Vị Thành khúc – Tống Nguyên nhị sứ An Tây

Vị Thành triêu vũ ấp khinh trần,

Khách xá thanh thanh liễu sắc tân.

Khuyến quân cánh tận nhất bôi tửu,

Tây xuất Dương Quan vô cố nhân.

Indeed, it’s a very important place!!!

I’m quite impressed with your erudition , linking Nguyên Dang Thinh ‘s plea to a

footnote anecdote about Liu Heng .

It shows as Fauklner would say : “the past is not dead ; actually , it’s not even past ”

Thousands of miles away and thousands of years past , the Confucean thinkings

( chinh danh ) and China’s history with minute details were still very much alive in the minds of the Vietnamese. It’s as you say ” the premodern past that haunts the Vietnamese ”

https://leminhkhai.wordpress.com/2016/09/02/the-premodern-past-that-haunts-modern-vietnamese/

It also shows how ridiculous that modern Vietnamese to try to concoct a history with an anti- chinese bias .

Recently , Japanese emperor Akihito 明仁has abdicated and left the throne to his son Naruhito 徳仁 ; Heisei 平成 era gives place to Reiwa 令和 era . I wonder why is it important to give a name to each new reign ? has it something to do with chinh danh ?

Thank you, but it’s more like “detective work” than erudition. . .

That’s interesting about the new reign name. I was curious to know where it comes from, and Wikipedia has an explanation. It says its from the early Japanese collection of poetry, the Manyoshu.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reiwa

It says “‘Reiwa’ marks the first Japanese era name with characters that were taken from Japanese classical literature instead of classic Chinese literature.”

If you look at some of those earlier terms, not only are they from “Chinese literature,” but there are also totally Confucian: Minh nhân 明仁, Đức nhân 徳仁. . .

Reiwa might not represent an anti-Chinese bias, but it is definitely pro-Japanese. . .

Googling possibilities of translating 天子 as heavenly prince led me to this post. 😂

Thanks! Very interesting document from Vietnam and great examination of its meaning.