Following on the previous two posts, it is time to start looking at the documents relating to the 1744 event where Nguyễn Phúc Khoát, the “Nguyễn lord” of Đàng Trong, elevated his status from “commandery duke” to “prince.”

The passage in the Nguyễn chronicles about this event indicates that in 1744 there was an auspicious sign in the form of an udumbara tree blossoming (ưu đàm khai hoa 優曇開花). This is a concept that comes from Buddhism. The udumbara tree, known in English as the cluster fig tree (Ficus racemosa), produces fruit without flowering, and supposedly only flowers once every 3,000 years.

In Buddhist texts, such as in the Lotus Sutra, the flowering of an udumbara tree is used to symbolize something very special and rare, such as the appearance of a Buddha.

Apparently inspired by this auspicious event, an official by the name of Nguyễn Đăng Thịnh submitted a request to the Nguyễn ruler that he “rectify the princely position” (chính vương vị 正王位). The concept of “rectifying positions” (chính vị 正位) is related to the practice of the “rectification of names” (chính danh 正名), a major concern of Confucian scholar-officials from the time of Confucius onward.

The idea behind the practice of the rectification of names is that names and reality have to directly correspond for there to be order in society. As such, in the case here the idea was that Nguyễn Phúc Khoát needed to “rectify the princely position” by actually declaring himself to be a “prince” because in the eyes of people like Nguyễn Đăng Thịnh (and presumably others) that is what he already was in the society of Đàng Trong at that time, but he was still being called a “commandery duke” (quận công 郡公).

Only excerpts from the document that Nguyễn Đăng Thịnh submitted are recorded in the ĐNTL, however, from those passages one can see that Nguyễn Đăng Thịnh clearly felt that “rectifying the princely position” was simply a first step that would lead to something much more significant, namely, to Nguyễn Phúc Khoát becoming an emperor.

For instance, Nguyễn Đăng Thịnh’s document reportedly stated that, “Rectifying names and duties in a kingdom is the starting point of renewal (duy tân 維新). Establishing rites and music for an age will accumulate moral virtue in excess.” (正名分於一國,維新之始,興禮樂於百年,積德之餘。)

These two sentences are filled with core Confucian ideas. Confucian scholars argued that not only was rectifying names essential for bringing order to society, but establishing the proper rites and music for regulating human behavior, and the relationship between the human world and Heaven, was likewise essential. What is more, Nguyễn Đăng Thịnh argued that such acts could lead to “renewal.”

This term “renewal” (duy tân 維新) was closely associated with a famous line in an ode in the Classic of Poetry about King Wen of the Zhou (Zhou Wen Wang 周文王) which states that “Although the Zhou was an ancient state, its mandate [from Heaven] was renewed” (Chu tuy cựu bang, kì mệnh duy tân 周雖舊邦,其命維新).

The King Wen that this ode celebrates was born as Ji Chang 姬昌. His family was from the state of Zhou which at that time was under the authority of the Shang Dynasty (16th century – 1046 BCE). Ji Chang served the Shang as Viscount of the West (Xi Bo 西伯) and gained a reputation for his good governance at a time when the Shang Dynasty emperor was infamous for the opposite.

After Ji Chang died, his son defeated the Shang Dynasty and established his own dynasty, the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE). He then granted his late father the title of “king,” which is why he is now referred to as “King Wen of the Zhou.”

Hence, the idea behind the line in the Classic of Poetry that “although the Zhou was an ancient state, its mandate was renewed” is that Heaven had already granted a form of mandate to the Zhou state, but the benevolence of Ji Chang’s governance led Heaven to “renew” its mandate, thus justifying the new position of the Zhou as a dynasty under Ji Chang’s son.

From a sentence like this one, it appears that Nguyễn Đăng Thịnh was arguing that by rectifying names and duties, such as by calling Nguyễn Phúc Khoát a “prince” rather than a “commandery duke,” and by establishing the proper rites and music, it would be possible for the Nguyễn realm to eventually “renew” its mandate and become a dynasty, just as King Wen’s benevolent rule reportedly enabled the same transformation to take place for the Zhou in antiquity.

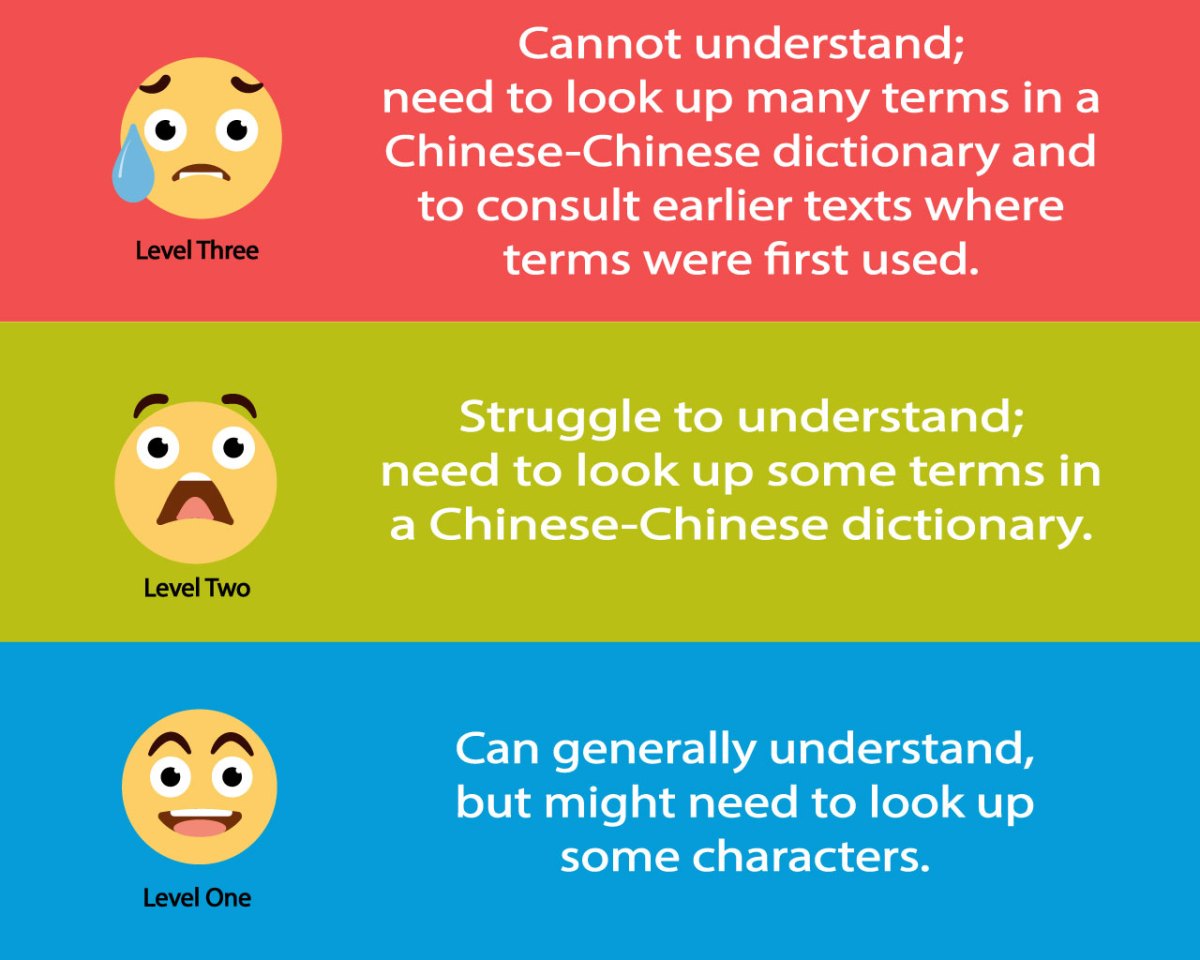

These two sentences are not particularly difficult to read in Hán. They fall somewhere between Level One and Level Two in the categorization (above) that I discussed in the previous post.

A reader might need to do some research to understand what the term “renew” (duy tân 維新) meant at the time, as it did have a very specific meaning related to the “renewing” of Heaven’s mandate. It is also necessary to figure out how to punctuate these two sentences.

Although neither of those tasks are all that difficult, the Vietnamese translation does not do a good job of rendering the meaning of these two sentences into Vietnamese.

It has: “Rectify names and duties when a kingdom is starting to renovate (đổi mới), organize rites and music after the moral virtue of a hundred years has been accumulated.”

(Chính danh phận khi nước buổi đầu đổi mới, sửa lễ nhạc sau khi tích đức trăm năm.)

The person who translated these two sentences did not punctuate them correctly, and therefore did understand them properly.

These two sentences are in a typical “topic” and “comment” format:

正名分於一國, Topic: Rectifying names and duties in a kingdom

維新之始。 Comment: is the starting point of renewal.

興禮樂於百年, Topic: Establishing rites and music for an age

積德之餘。 Comment: will accumulate moral virtue in excess.

Beyond misunderstanding the grammar of the sentence and translating it inaccurately, an even bigger problem is that translating the very specific term “duy tân” (renew) as “đởi mới” (renew/renovate) makes it impossible for a reader to see the connotations that are connected to a term like duy tân.

These are only the first two sentences of many more to come, but we are off to a bad start. . .

See you in the next post.

This Post Has 7 Comments

Is the paragraph in Vietnamese above taken out of the Đại Nam Thực Lục, which was translated by the Viện Sử Học team led by Đào Duy Anh?

Also, can you please provide us readers who don’t read Chinese those two sentences in Hán Việt – so we can try to understand them? Thank you.

Yes, that’s the one.

I’m not all that good at transliterating Chinese into Hán Việt because sometimes a character will have more than one pronunciation, and I can sometimes be wrong in choosing which one to use.

I use tools like this one to help:

http://vietnamtudien.org/hanviet/

But this is a try:

Chính danh phận ư nhất quốc duy tân chi thủy,

Hưng lễ nhạc ư bách niên tích đức chi dư.

And the way I break up these sentences is as follows:

Chính danh phận ư nhất quốc, duy tân chi thủy,

Hưng lễ nhạc ư bách niên, tích đức chi dư.

Thank you

_ according to chinese sources , Đàng Trong is written 塘中 đường trung ; đường basically is a dike . Between the two conflicting realms , were built several defensive walls ( lũy 壘 ) by the Nguyễn ; they were situated near the 17th parallel .

So Đàng Trong maybe means inside the wall

_ udumbura ưu đàm , in vernacular is called cây sung ; its fruits are plentiful but bland , unappetizing . I don’t see why it’s so revered .

I apologize since this is a bit off-topic. I notice the picture in the heading depicts a ca trù singing and dancing performance. May I ask for the original source of the photo? Thank you so much!

(Very informative and visually appealing article anyway)

Sorry, but unfortunately I have no memory of where it came from, and I can’t find the place where I must have originally saved that picture. . . I have things spread over so many computers and back HD’s now. . . If I do find it though, I’ll let you know.

It may come from this database: https://collection.efeo.fr/ws/web/app/report/index.html