The earliest record that tells us something about life in the Red River Delta in ancient times is Li Daoyuan’s sixty-century Shuijing zhu 水經注 (Annotated Classic of Waterways). That book cites an earlier work, the late-third or early-fourth-century Jiaozhou waiyu ji 交州外域記 (Annotated Classic of Waterways), to say the following about agricultural practices:

“In the past, before Jiaozhi had commanderies and districts, the land had lạc fields. These fields followed the rising and falling of the. . [KEY WORD]”

交趾昔未有郡縣之時,土地有雒田,其田從潮水上下. . .

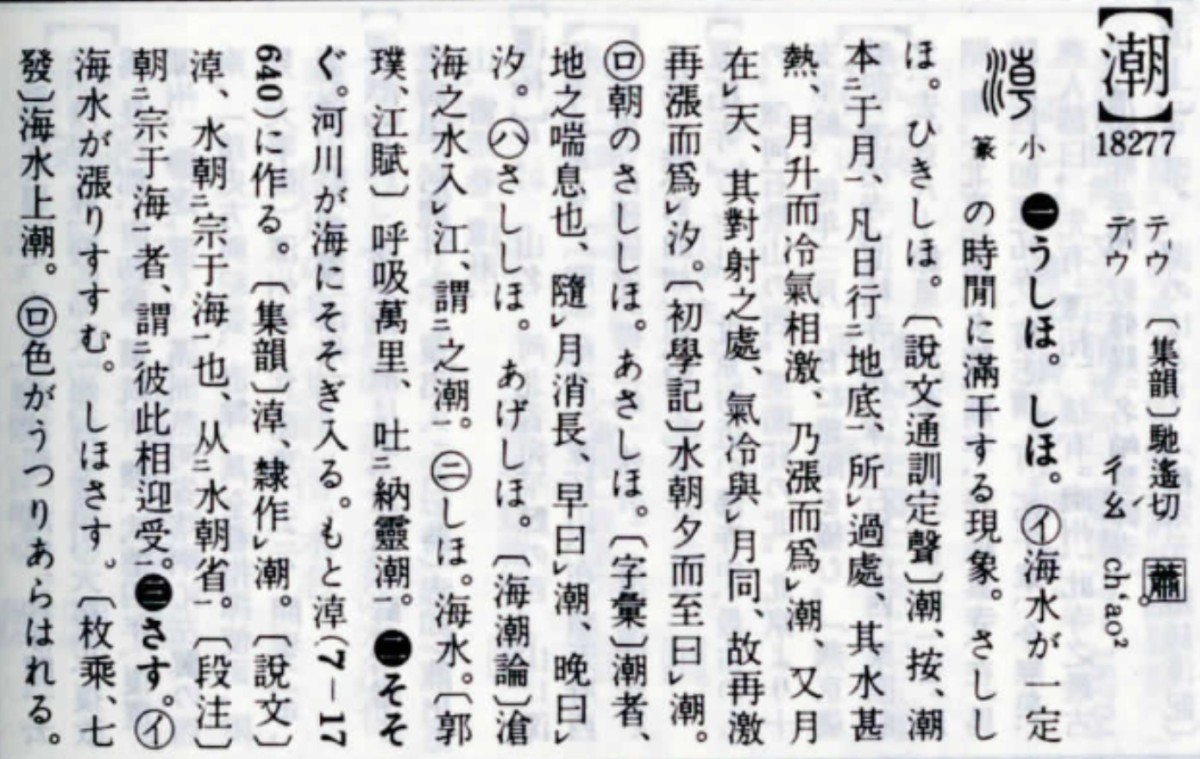

The next word in that sentence is very important, and it has caused a lot of confusion. It is chao/triều 潮. The basic meaning of this word is “tide,” and scholars have understood this sentence as saying something about tidal waters.

In 1918, for instance, French scholar Henri Maspero, translated this passage as follows:

“In the past, before Jiaozhi had been divided into commanderies and districts, its territory formed lạc fields, where the water rose and fell following the tide.”

[“Autrefois, au temps où le Kiao-tche n’était pas encore divisé en commanderies et sous-préfectures, son territoire formait les champs lo (lạc) 雒田, où l’eau montait et descendait suivant la marée.” (8)]

Later, in the 1930s, French geographer Pierre Gourou made an extensive, and influential, study of the Red River Delta that he published in 1936 as Les Paysans du Delta tonkinois: Etude de géographie humaine.

In that book, Gourou included a very brief section on tides and their limited ability to spread inland. In that section he stated that,

“The tides may occasion intrusion of salt water into the rice fields, and that is the main danger of them. To be sure there are kinds of rice which can tolerate a rather heavy salt content in their water, but an excessive concentration would ruin the crop. Therefore, rigid diking is necessary to check the salt water.” (pg. 82 of English version)

Then later in the century, we can see the ideas of Maspero and Gourou get repeated in English-language writings.

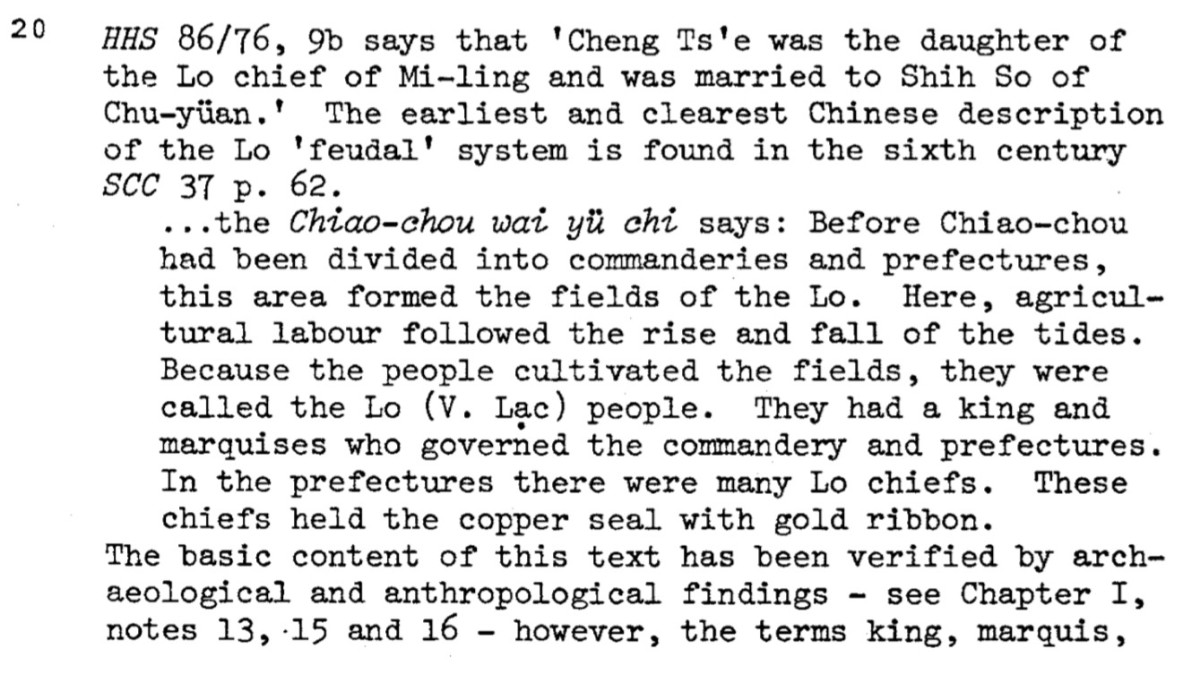

In 1979 Australian historian Jennifer Holmgren followed Maspero’s wording and wrote in English that “Before Jiaozhou had been divided into commanderies and prefectures, this area formed the fields of the Lo. Here, agricultural labor followed the rise and fall of the tides.” (37)

Then in 1983, American historian Keith Taylor included in his The Birth of Vietnam a map on “Tidal Influence in the Hong River Plain in Modern Times” based on a similar map in Gourou’s book (11), and stated that “The practice of tidal irrigation, as described in the texts that mention Lạc fields, reveals a relatively advanced agricultural technology.” (12)

At the same time, however, in a footnote to that statement, Taylor stated that “Yumio Sakurai has recently conjectured that the description of Lạc fields as tidal is simply a contrived elaboration to explain the name Lạc and that ancient agriculture in Vietnam was based on agronomic expertise, not water-control engineering; this review deserves more study.” (12)

Japanese historian Sakurai Yumio published an article in 1979 in which he argued that early Vietnamese had not made use of the tides in agriculture, that is, that they had not engaged in what can be called “tidal irrigation.”

A summary of his argument can be found in the above image. Essentially he argued that there was no evidence that anything Gourou discussed had existed in ancient times, that the location of the lạc fields was not close to the coast, and finally that different types of rice were grown in the Red River Delta, and that perhaps a variety that was somewhat resistant to salt water had been noticed by Chinese in the past, and that this is what was recorded.

While Sakurai’s evidence is important, the character (chao/triều 潮) that scholars have understood to mean “tide” does not have to be understood that way as it had more than one meaning, because it was used as a variant for other characters.

First of all, this character was a variant for chao/triều 𣶃, which was defined in the early-second-century-CE, dictionary, the Shuowen 説文, as meaning “water rightfully retuning to the sea” (水朝宗于海). This definition has a moral sense to it, and the wording of this definition was itself used to symbolize the attitude that vassal lords should have toward the emperor, someone they should always “rightfully return to” just as water “rightfully flowed toward the sea.”

The character, chao/triều 𣶃, was also a variant for tao/đào 濤 or its own variant 𤁟, which the Shuowen defines as “a large wave” (大波也). This is the version that is important for our understanding of that passage.

Tidal irrigation is complex and difficult. It requires that one collect salty sea water (that is pushed inland with the tide) in a pool and then add fresh water to dilute the water so that the salt will not kill plants.

What is more, if “agricultural labor followed the rise and fall of the tides,” as Holmgren translated that line in the Jiaozhou waiyu ji, this would mean that people would have had to engage in this complex labor every single day.

However, archaeological evidence of such pools, or of early sea dikes, does not exist.

There is also no solid linguistic evidence either. Indeed, Mon-Khmer languages have very few words for “tide.” This is not surprising, as the Mon-Khmer languages emerged in the inland area of mainland Southeast Asia. Mon-Khmer speakers were not coastal peoples.

As such, rather than seeing this passage as saying that lạc fields were cultivated following the rising and falling of the (daily) tides (chaoshui shangxia/triều thủy thượng hạ 潮水上下), it would make more sense to employ another meaning of chao/triều 潮 and to understand that the lạc fields were cultivated following the (annual) rise and fall of the “wave of water” (taoshui shangxia/đào thủy thượng hạ 濤水上下) that came down the Red River and flooded the fields.

If that was the case, and given the lack of evidence of large irrigation works from this early period, it was probably also the case that the people at that time grew rice by “broadcast seeding” rather than by growing seedlings first and then transplanting them.

So when did full-scale wet-rice agriculture start to take place? I’m not sure, but certainly increasing contact with Tai-speaking peoples in the late first millennium CE, as Southwestern Tai-speakers started to migrate away from the Guangxi region, would have exposed Vietnamese to their complex water control techniques.

And in the period between 1,000 and 1,500 we do find evidence in the Vietnamese annals of major dikes getting built along the Red River.

Perhaps that is when “relatively advanced agricultural technology” really started to be developed in the Red River Delta.

This Post Has 27 Comments

An alternative explanation is that the ancient Vietnamese were indeed of Tai ethnicity. Then everything will fall into place. Lac is a Tai word and should be looked up in a Tai-Kadai dictionary instead of Mon-Khmer. And the hypothesis that Vietic people moved into Red delta river around the end of the first millenium also becomes more plausible. Some authors did mention the people of Jiuzhen did not pratice rice growing while the Jiaozhi people grew ample rice for themselves and they traded rice for other goods from Jiuzhen. It would have been not possible for Jiaozhi to support such large population (largest compared with other commanderies in Jiaozhou) during Eastern Han if there had not been advanced rice culture pratices already in place.

Ðông quan Hán ký: Tục Cửu Chân là đốt cỏ rồi gieo giống làm ruộng.

“Jiuzhen custom was used milpa to plant rice”

I think Jiuzhen people in the past used milpa, first burning the forest and then using that land to plant rice.

I think in the 500 BC period, the proto-Vietic people live side by side with proto-Tai.

First, Muong ethnic and all of others belong to Vietic branch live south of Red River Delta or more exactly south of Red River.

Second, who is Thuc Phan. There is a hypothesis that Thuc Phan aka King An Duong was from tục pắn – a Tai word means leader. This is somehow make sense because he was from the north of Red River Delta, a region with the dominance of Tai-speaking people.

Third, Muong ethnic has a good relationship with Thai ethnic as well as Muong borrow some Tai words make it more plausible.

So, I think Vietnamese people today has proto-Vietic and proto-Tai ancestors.

Thanks for the comments, but it is clear that none of you are aware of what experts in the field of Tai historical linguistics actually argue. That is understandable, because other than one article that I wrote. . . that mentions the ideas of actual experts on Tai historical linguistics, no one who works on Vietnamese history has ever mentioned what such experts say. Further, there is no one in Vietnam who is an expert on Tai historical linguistics, and there has never been a Vietnamese expert on Tai linguistics. Everything that has been written about “the Tai in Vietnam in antiquity” has been a “guess” based on no solid linguistic evidence.

There are three branches of Tai languages: Central Tai, Northern Tai and Southwestern Tai. The “youngest” is Southwestern Tai.

The leading scholar of Tai historical linguistics today is Pittayawat Pittayaporn (Cornell University PhD in 2009). He has classified all of the Tai languages in Vietnam as Southwestern Tai languages:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tai_languages#Pittayaporn_.282009.29

He has also dated the movement away from an original homeland in Guangxi of Southwestern Tai speakers to the end of the first millennium AD (8th and 9th centuries). He has done this through reach search that is MUCH MORE SOPHISTICATED than any research about Tai peoples that has ever been produced by people who focus on Vietnam.

To quote,

“The current ethno-linguistic landscape of mainland Southeast Asia is due in large part to the spread of SWT [Southwestern Tai] speakers from southern China. A lack of historical record makes the dating of the SWT expansion a difficult task. As this study has shown, linguistic evidence can help shed light on this important prehistorical event. More specifically, Chinese loanwords in PSWT [Proto-Southwestern Tai], the hypothetical ancestor of all SWT languages, are important evidence for the dating of the spread of SWT languages. Altogether four layers of Chinese loanwords existed in PSWT, namely PreLater Han Chinese (Pre-LH), Later Han Chinese (LH), Early Middle Chinese (EMC), and Late Middle Chinese (LMC). Crucially, the LMC layer indicates that the SWT spread must have started after the EMC period. In collaboration with nonlinguistic evidence, the loanword evidence suggests that SWT began to spread southwestward in the last quarter of the first millennium CE.” (64)

http://www.manusya.journals.chula.ac.th/files/essay/Pittayawat%2047-68.pdf

People need to stop “guessing” about the history of Tai-Viet relations, and actually READ what REAL EXPERTS have written. What people who are actual experts on the topic say DOES NOT MATCH what countless people who are not experts keep saying about Vietnamese history and the supposed role of Tai-speaking peoples there in the past.

Scholars outside of Vietnam all agree that Southwestern Tai speakers migrated away from the Guangxi region in the late first millennium AD. It’s not by any means just Pittayawat Pittayaporn who thinks that way. He’s just the leading scholar in that field now. And there are NO EXPERTS on this topic in Vietnam, and never have been. There have only been people who have made guesses about what might have happened, but they did not base those “guesses” on the kind of solid historical linguistic scholarship that people like Pittayawat Pittayaporn are capable of engaging in.

I think not all of Tai-speaking people in Vietnam belong to Southwestern Tai. Yes, Thai is southwestern Tai but Tày is not. Tày is Central Tai actually.

As for Pittayawat Pittayaporn’s point of view. Tày is belong to Zuojiang Zhang–Southwestern Tai. Only Thái belong to Southwestern Tai. Tay is belong to Zuojiang Zhang (?).

Btw, in his book, page 40, Figure 1-3, he draw Tay belong to Central Tai. You can see again in page 313-315.

And the Seak, Yay (Sách và Giáy in Vietnamese) people belong to same group with other Northern Tai in his classification.

Seak is NT and he claim the same but Giay is CT but he claim it is NT.

In page 304, he actually claim that all kind of other way to divide Tai into Central, Southwestern, Northern are false.

In my understand, he didnot give any idea about such a Southwestern branch or claim anything about latter immigration (?)

“As has become clear, the preliminary subgroup structure proposed here shows characteristics that depart greatly from the conventional three-way classification. It does not recognize either Li’s CT or NT as genealogical subgroups, even though subgroup N resembles NT rather closely. Nor does it view SWT as one of the primary branches. Most importantly, it claims that the Tai family tree is rather flat as it consists of more than two primary branches. In short, the reconstruction of PT phonology proposed in this study implies a subgroup structure radically different from all earlier proposals.”

Thanks, but look at the article that I linked to. It clearly points out that Southwestern Tai speakers moved away from Guangxi in the late first millennium AD.

Pittayawat Pittayaporn does not argue that there were “no” Tai-speakers outside of Guangxi before that time, but he argues that the large-scale numbers of Tai-speakers who could have an influence on other societies did not start to appear in the Red River Delta until the late first millennium AD.

Chinese sources report the arrival of such peoples in the Red River Delta at that time as well:

https://leminhkhai.wordpress.com/2011/10/07/mang-savages-in-the-red-river-delta/

@ Le Minh Khai: I agree with you that there was a large scale of Tai-speaking people who probably mostly was Southwestern Tai.

However, I think it is only the case about the west of northern Vietnam (even include Thanh Hoa, Nghe An). The present of Thai ethnic in the west is late.

Nonetheless, I think Tay ethnic was not the same with Thai. I read some about them. Most of the case, Tay is belong to Central Tai or some claim that it is kind of mixing Central and Southwest.

Did proto-Tai group such as proto-Tày has any influence in proto-Viet ethnic earlier than 8th century? It is possible actually.

According to language, all of Vietic branch was speak south of Red River. North of Red River is the dominance of Tai-speaking people.

In my opinion, it is highly likely that south of Red River is proto-Vietic world and north side is proto-Tai world. I even think the region between two river (Red River and Thai Binh River) is the place two group live side by side before the time of Han’s conquer.

Thank you for providing us with a very informative article. But as a layman in this esoteric field, I would rather base on common sense logic than information studded articles. Sorry to say that.

Here is the logic flow of my argument:

1. No one knows for sure who were ancient Vietnamese in Red River Delta, it could be Vietic or Tai. This of course requires solid evidence but alternative statements like they were only Tai, or only Vietic could be easily refuted since An Duong Vuong was at least an outsider who conquered the people of Red river delta. He could be a Shu prince, or a chieftain from Tai.

2. A branch of Tai definitely moved out of China late in the last quarter of the first millenium (this I totally agree base on your article)

3. Tai mass migration influenced the societies in South East Asia in terms of language and others, for example, agriculture. But clearly it is hard to believe Tai did have significant influence on An Nam/Dai Viet societies. For example, you mentioned that Tai influenced Red River Delta people on improved rice irrigation from 10th century onward. I find it hard to believe that the Red river delta people needed to learn anything from Tai immigrants, who societies were probably not much more advanced than the native people where they moved in. 1000 years with Han, particularly from Jiangnan (who mastered rice irrigation as far back as the Yue kingdom during ChunQiu) unquestionably made Vietnamese in 10th century already experts in rice culture. What else can they learn from Tai?

So although you berated us for basing on guess and not solid evidence, I personally think that our guesses are as healthy as scholarly evidence. It keeps people like you on your toes, not digging too deep into indirect evidence (however solid) such as languages and historical archives but also at least pay attention to common sense and other evidences such as genetics and anthropology too.

Thanks for the comment!!

One of the reasons why people have “assumed” that Tai peoples must have been in the Red River Delta from an early time is because the Vietnamese language today contains words of Tai origin that related to water control:

mương: irrigation canal

mương phai irrigation; drainage

Indeed, Tai peoples created a very complex system for water control that people refer to as the “muong phai system.” The first page of this article explains a little about it:

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwjw2Lymo-jTAhVN_mMKHcIED7QQFggsMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.niu.edu%2Fgeog%2Fimages%2FGIS%2520Mapping%2520Tai_2000.pdf&usg=AFQjCNFRbIxyxzugjJ76LHKxIDm_57FS0A&sig2=1RBnsfMrA8qmAKN7MjA1Dw

My “guessing” about the influence of this technology on rice production in the Red River Delta is because I haven’t researched about it, but the little that I have seen makes it obvious to me that there is probably strong evidence for what I think.

One problem we have is that we “assume” that Vietnamese have always been growing rice the way they do now (with dikes along the Red River that prevent flooding, etc.). That’s not the case, however, and so we need a clearer history of what things were actually like.

In the Dai Viet su ky toan thu, there are no mention of dikes in the period of Chinese rule. 1248 is the first time a major dike building project is mentioned.

Similarly, in southern China dikes didn’t start to get built in the Pearl River Delta until the Tang, but the big construction came during the Song. See pages 76-79 of this book:

https://books.google.com/books?id=dBsfts9wyRsC&pg=PA69&lpg=PA69&dq=lingnan+broadcast+rice&source=bl&ots=kxF9Z2PpEl&sig=5ihIqz-r0yDZ68s-32wwb2s3ALw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjDk6LpnujTAhUB_2MKHT4UDAgQ6AEILDAB#v=onepage&q=lingnan%20broadcast%20rice&f=false

So how did people grow rice before the big rivers were controlled? That’s the part I want to know more about, but this brief post here indicates to me that we might discover that “broadcasting seeds without transplanting” was the norm.

http://http-server.carleton.ca/~bgordon/Rice/papers/peng-87.htm

To be able to engage in intensive wet rice cultivation (where seedlings are transplanted) requires very sophisticated water control. We “assume” that such sophisticated water control has long existed in Lingnan and the Red River Delta, but we don’t have actual evidence for that.

I don’t think that Tai-speakers taught Vietnamese and Chinese how to build dikes along the Red and Pearl rivers. However, their knowledge of how to move water from rivers into fields by means of irrigation canals (mương phai) could have enabled Vietnamese to cultivate the fields along the diked Red River more effectively, and that could explain why the Tai word for irrigation canal is in Vietnamese. The timing of the spread of Southwestern Tai languages and the development of water control in the Red River delta both fit such a hypothesis.

Thank you. You again provided us with valuable sources. I was quite surprised to learn that Tai (Zhuang) invented irrigation. I always assumed that already happened in Hangzhou basin much earlier.

Oh, I don’t think we can say that Tai irrigation techniques influenced people in the Hangzhou basin. I really don’t know about this topic, but my guess would be that irrigation knowledge developed in the Hangzhou area separately.

But in the southwest, it was the Tai who developed the best irrigation skills.

About the theory of SWT immigration affected the Kinh ethnic, I think it has some problems. First, linguistically, Vietnamese has some word from Hlai, another branch of Kam-Tai family (A Phonological Reconstruction of Proto-Hlai). proto Tày people maybe live in north VN earlier from An Duong Vuong period. If central Tai-speaking people use irrigation cannals first. Is this path from Guangxi to Lang Son valley is far more shorter than moving to the west then follow the Red River in 8th century?

Sagart (I think you know him) in “The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia” believe that Tai-Kadai actually born in Hainan and Red River Delta 4000 BP.

The Hainan indigenous Hlai people has another name Li (Lê in VNese) and the people live “between two river” was called Li (Lý in VNese). So can we have a guess that some part of VNese in even 3th century AD was Tai-speaking people?

Sagart (controversially) argues that Tai-Kadai languages are a branch Austronesian.

He says in that chapter that “the events leading to PTK [Proto Tai-Kadai] might run as follows: in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE [i.e., 2,500-2,000] a group of speakers of a Puluqic dialect (‘FATK’, Formosan Ancestor of Tai-Kadai) left eastern Taiwan by boat in search of new agricultural land. They found it on the coast between the Red River delta in north Vietnam and the Pearl River delta in present-day Guangdong province of China. In that region they eventually came into intimate contact with, and underwent strong pressure from, a population of mainland farmers speaking a language who affiliation is difficult to establish, but with possible phylic or macrophylic connections to Austroasiatic.” (pg. 151)

https://www.academia.edu/3077307/The_expansion_of_Setaria_farmers_in_East_Asia

Sagart is talking there about Proto-Tai-Kadai. From that language later emerged Proto-Tai, and from that language still later emerged Central, Northern and Southwestern Tai.

Linguists who work on Tai languages feel like we can talk start talking about a Proto-Tai language spoken in the Guangxi-Guizhou area around 2,000 years ago. And again, they see Southwestern Tai speakers migrating away from there around 800-900 AD.

Could there have been some speakers of Central Tai in the northern mountains of what is now Vietnam in 300 AD. Sure. But the kind of intercultural contact that led to the adoption into Vietnamese of Tai words relating to wet-rice agriculture had to have come at a time when there was significant contact between Tai and Viet speakers, and that didn’t happen until the late 1st millennium AD when Soutwestern Tai speakers started to migrate away from the Guangxi area.

That migration (or those migrations) must be related to the transformations that took place at that time in the region as the Kingdom of Nanzhao became powerful, fought with the Tang. and captured the Red River Delta in the ninth century.

Farmers generally don’t move unless there is major pressure to do so. Population pressure can be one such type of pressure, but war is another. The time period in which Southwestern Tai speakers migrated was a time of warfare that also affected the Red River Delta. Besides the linguistic evidence, and the evidence we have about water control and rice growing in the Red River Delta, this political-history evidence also supports the idea that significant Tai-Viet contact only started to take place in the late first millennium AD.

On the US involvement in the Vietnam war , there are two narratives: the orthodox one ( terrible mistake ) and the revisionist one ( noble endeavour )

On Vietnamese history , as far as I know , there are also two points of view : the nationalist one ( essential VN people

and culture , I wiould tentatively call Gaulois – Nôm ) and the revisionist ( Han viêt )

What is the state of opinion among the VN historians ‘ community ? It seems , the orthodox is still overwhelmingly in favor . B. Kiernan who is essentially a Cambodian history expert , for his first wading in Vietnam history ,has not apparently learned of the revisionist version

I would say that there are 3 narratives of the war: the two that you mention and then one which people call “the Vietnamese studies” narrative (i.e., people who make use of Vietnamese sources). That group includes the people we’ve talked about before (Miller, Asselin, Nguyen, etc.). None of those scholars see a “noble endeavor” anywhere, but they also think the “terrible mistake” narrative is too simplistic.

As for the other point, I don’t think there are really two narratives yet. There is the nationalist one, as you point out. That’s being “deconstructed” by people who can read the primary sources in Han. But those acts of “deconstruction” have not led to a new narrative yet.

It’s coming though. . .

@ Le Minh Khai: do you happen to know from what language the word kênh/kinh (ditch) and mạ (rice seedlings) stem? I assume they are of Tai too.

I would want a linguist to confirm this, but it looks like that “seedling” might come from Tai. There are a couple of online dictionaries that are helpful. This one is a comparative Mon-Khmer dictionary (http://sealang.net/monkhmer/dictionary/) and this one (http://sealang.net/crcl/proto/) has information about what linguistics think could be proto-Tai (PT) and proto-Southwestern Tai (PSW). You can search in English in the second dictionary, and you can search for English terms in the first dictionary by using the “text” box.

In searching for “seedling,” the Tai term that comes up is “klaa” (the “k” is pronounced like a “g”), and in the Mon-Khmer dictionary it looks like the northern MK languages have something like this, but the southern ones don’t. That said, can “klaa” change to mạ? I’m not sure. That’s what I would want a linguist to help with.

กล้า klâa “young rice plant; rice seedling (as is)”

Brown: cited. Note: no Shan cognate

Jonsson: [ *kl- (C2) B89-1 ] PSW: *kla “young rice plants”

Li: [ *kl+a (C1) 11.1:220 ] PSW: *klaa PT: *kla

As for kênh/kinh, my guess would be that this comes from the Chinese word meaning a path: jing 徑.

I think there is a loophole in the argument here. If there was a significant Tai community speaking in Vietnam prior to mass movement of Tai into South East Asia, it still did not violate the premise that Tai spreaded irrigation techniques to South East Asia. Suppose that this isolated Tai community in Vietnam did not have contact with SW Tai community in Guangxi due to some unknown reasons, then it is still logical for them to learn the new vocabublaries from their cousin in later time. To prove or disprove the existance of a Tai community in Vietnam before the arrival of Han, we have to look at language, anthropology and historical evidence.

Yea, and that’s why I need to talk to Tai linguists again, because I recall being told that the “fai/phai” in “muong phai” is a Southwestern Tai pronunciation.

In any case, the foremost scholar on Tai linguistics today – Pittayawat Pittayaporn – is the person who has taught me what I know about this topic. So if you think there are loopholes, he is the person you should take that topic up with:

http://pioneer.netserv.chula.ac.th/~ppittaya/

For now, I’m going to assume that he is right, as he knows more about this topic than anyone else in the world.

I don’t know about archaeological evidence, but there is some record book about Giao Chi such as: Sách Dị vật chí của Dương Phù (thế kỷ I) chép: “Lúa ở Giao Chỉ mỗi năm trồng hai lần vào mùa hè và mùa đông” or . (Sách Ðông quan Hán ký nói rằng: Tục Cửu Chân là đốt cỏ rồi gieo giống làm ruộng. Sách Tiền (Hán) Thư nói: Thời họ Triệu, Ðô Úy Sưu Túc sang dạy người ta dùng bò để cày bừa). Dân thường phải mua lúa Giao Chỉ mỗi lần bị thiếu thốn.

Li Tana already talk about people in Hợp Phố have to bought rice from Giao Chỉ.

It means Giao Chi people has a good agriculture technique to make rice productively.

If Giao Chi people only know broadcast seeding. They can not have much rice in order to feed 600 000 people and export to Cuu Chan and Hop Pho.

It is a very weak evidence but at least it can prof that the agriculture technique in Giao Chi is not so pure like only broadcast seeding.

Another small evidence that even in Dongson period, Giao Chi people use plough. It means they know how to make the land more fertile.

Another evidence is after “pacified the Trung sister rebel”, Ma Vien build castle, bore canals and “tháo úng đồng ruộng”.

I don’t know about the last term whether or not appear because it was a Vietnamese soure, I cannot found the original Chinese source, but if he bore canals. Is this for sure for agriculture.

I think it is hard to believe that only 8th century AD, proto-Vietic people just know about the way to make water into rice field.

Thanks for pointing out these passages. You’ve made me think of some interesting things about how people write history today, and I’ll write about that on the blog soon.

As for the Ma Vien quote, that is referring to things that he did after fighting the Qiang people in Shaanxi/Gansu.

Finally, I don’t think that people had “no idea” about how to irrigate before the end of the first millennium AD. What I’m arguing is that the building of large dykes along the Red River didn’t start until then, and significant contact with Tai-speaking peoples and their irrigation techniques did not happen until then.

What about James R. Chamberlain? Don’t you think that he is also a very knowledgeable scholar on the field of Tai linguistics ?

You really need to ask people in the field about that. I am assuming that he is.

What I take issue with are his efforts to use historical evidence to document the undocumented history of Tai-speaking peoples.

I’m not critiquing his linguistic knowledge. I have no ability to do that. I am critiquing his historical methodology. As an historian of the time period he looks at, and as someone who can read the actual sources for that period in their original language, I do have the ability to do that.

And one more point, what archaeological evidence do we have of irrigation in say 100 AD?

Greetings Liam,

I am interested in the cultural influence of tides. I found your article and subsequent q&a interesting. I had only a very brief opportunity to visit Bach Dang River a few years ago focused on museums/temples and didn’t get a chance to investigate tidal rice production. If I followed your comments, tidal rice production began in first century AD. Correct? Do you have any information as to changing scale of production or relative importance over the centuries, or of technological advances? Do you know if there were tide-powered rice mills in Vietnam?

I live in Connecticut and am going to South Carolina next week for vacation and to investigate tidal rice production there during the Colonial period of the 1600s and 1700s. My understanding is that there were several key elements of tidal rice production in SC:

1) fresh water tidal: Rice was grown well upriver of the coast where there are tides of 6-12 feet, but where the salt water wedge did not reach; 2) fields were not flooded daily, but four to six times per year for period of weeks at a time to spread alluvium, kill weeds, support stalks. Gateminders would open irrigation gates to let water in or out to keep the water at the proper depth for the relevant activity. Fields were drained for sowing, additional weeding, and harvesting. Is this how it was/is done in Vietnam?

Tide-powered rice mills were introduced in the 1700s and operating into the 1900s (I think—should get better answer next week)

Any infö you can provide would be much appreciated. Thanks. –Mark

Hello Mark, actually, no, I don’t know of any clear historical evidence of tidal rice production, so I do not argue here that tidal rice production began in the 1st century AD.

There is one historical reference that uses the term “tide,” but I try to show here that that same term can simply mean “inundation,” and that the type of rice production was probably the broadcast seeding of flooded fields (that was the norm in Southern China at that time too).

The comments to this post went off on a linguistic tangent, as people have used linguistic terms to guess that tidal rice production existed, but there is no archaeological evidence for it (that I am aware of).

Yes, I’ve read about places like South Carolina, and again, people have not found evidence of irrigation gates or fields like existed there.

One thing I’d be interested to know about South Carolina is why people think that form of cultivation began there. Wouldn’t it have been easier just to move to a place where cultivation was less difficult? What would have prevented that? I’m assuming that there must be good historical reasons for why people chose to engage in that form of cultivation at that time.

Hello Dr Liam!

Could you give me your insights into the view of James R. Chamberlain in his paper:

https://www.academia.edu/26296118/Kra-Dai_and_the_Proto-History_of_South_China_and_Vietnam

This guy has many interesting ideas about the origin of Vietnamese but according to you he is not a real expert in Tai.