[For an addendum to these opening comments, see this post.]

Ben Kiernan begins his new Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present with the following sentence: “The mountains are like the bones of the earth. Water is its blood,” wrote a Vietnamese geographer in 1820.” (1)

That sentence is the perfect sentence to open this book, as it perfectly symbolizes how flawed the scholarship in the pages that follow is.

Kiernan claims to be quoting G. Aubaret’s 1863 (really bad) translation of Trịnh Hoài Đức’s 1820 gazetteer of the south, the Gia Định thành thông chí.

However, Aubaret wrote “L’eau est à la terre ce que le sang est dans les veines de l’homme: elle a comme des alternatives de respiration et d’aspiration pendant lesquelles elle avance ou se retire.”

[Water is to the earth what blood is like in the veins of man; it has alterations of breathing in and breathing out, during which it advances or withdraws.]

That’s not the same as “The mountains are like the bones of the earth. Water is its blood.”

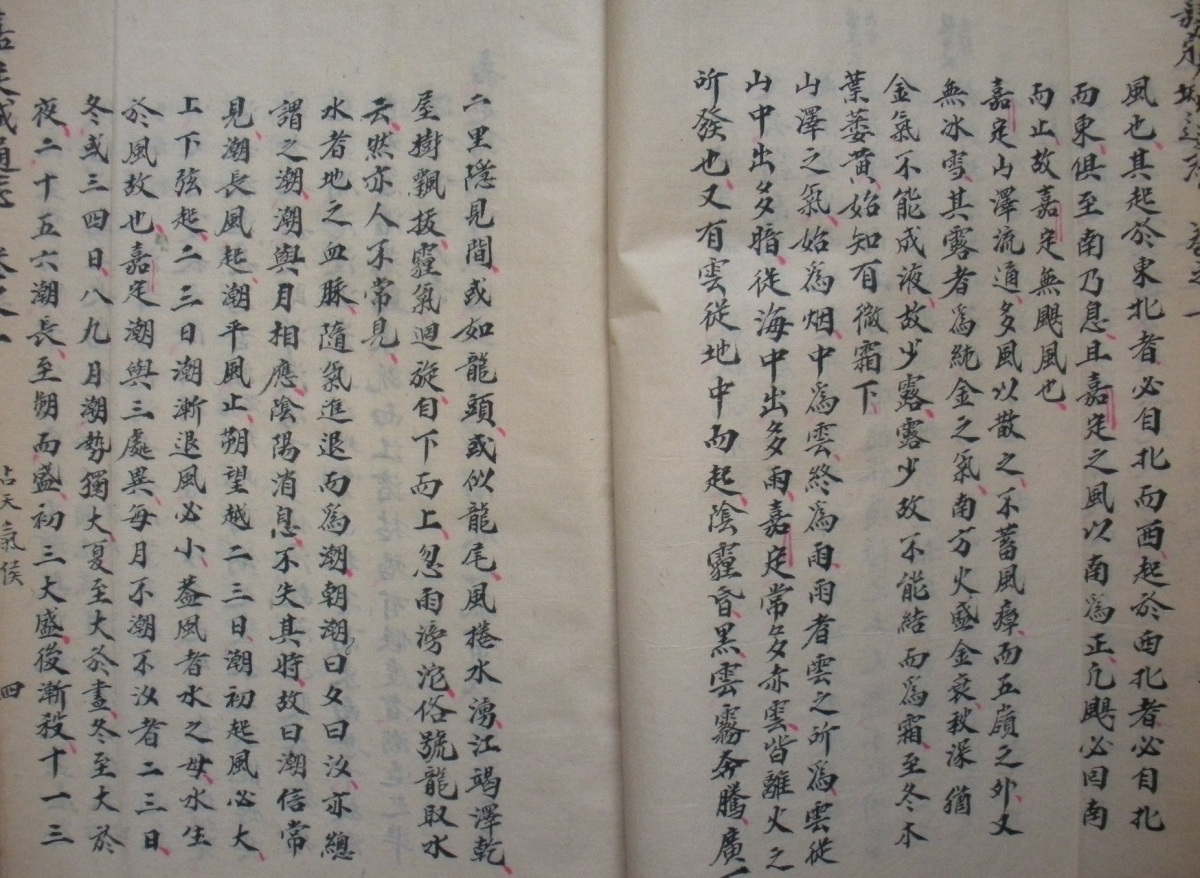

The text that Aubaret claimed to have “translated,” meanwhile, was written by Trịnh Hoài Đức in classical Chinese and was not the same as what Aubaret wrote either. That passage repeats something that was written in Wang Chong’s 王充 first-century CE Balanced Discourses (Lunheng 論衡) where it explains how tides are created:

“Water constitutes the earth’s arteries. Tides are created by the intrusion or extrusion [in the earth’s arteries] of khí/qi.”

水者,地之血脈,隨氣進退而為潮。

If we could go back in time and get Wang Chong to understand what Kiernan wrote, I suspect that he would be very surprised, as would Trịnh Hoài Đức, as “The mountains are like the bones of the earth. Water is its blood” is not what these men thought or wrote.

Instead, it’s a “double-distortion.” Aubaret did not understand what Trịnh Hoài Đức had written and Kiernan willfully twisted Aubaret’s bad translation yet further.

Given that so little work had been done on Vietnam when Aubaret made his translation, we can understand why it would be flawed. However, here in the twenty-first century the field of Vietnamese history has developed in places like North America to the point that it can no longer tolerate such flaws, let alone “double-distortions.”

That said, the problem with this book is much deeper than the problem of relying on bad translations, even though working with (and distorting further) bad translations leads to complete distortions of the Vietnamese past.

As the previous posts have indicated, there are conceptual problems with this book, there are methodological problems with Kiernan’s scholarship, and Kiernan’s understanding of the scholarship on Vietnamese history is woefully outdated.

And then there are the factual mistakes. Oh, there are so many factual mistakes!

Just to give a couple of the many examples that one could point to, Kiernan says on page 53 that King An Dương, a well-known figured in early Vietnamese history, is described in a Chinese source as a prince of the kingdom of “Chu.”

This should be “Shu.” Chu 楚 and Shu 蜀 were two separate kingdoms.

After discussing King An Dương’s conquest of Văn Lang, Kiernan says, apparently following Henri Maspero’s early-twentieth-century dismissal of King An Dương as legend, that “All this occurred within what is now China. It was Zhao Tuo (V. Triệu Đà), not his predecessor, who subsequently took over the Lạc regions to the south, within modern Việt Nam.”

King An Dương is discussed in a text called the Jiaozhou waiyu ji 交州外域記 (Record of the Outer Territory of Jiaozhou) in relation to a place called Jiaozhi/Giao Chỉ 交趾. That refers to northern Vietnam.

What is more, the passage about King An Dương in that text comes right after a passage about “lạc fields” which Kiernan himself mentions on pages 41-43 as a sign of early “aquatic agriculture” in the Red River Delta.

So according to this logic, the “lạc fields” were within modern Việt Nam but King An Dương, who is recorded in the same text as conquering the area where the lạc fields were located, was in China. . .

And with regard to the term “Jiao/Giao” in Jiaozhi/Giao Chỉ or Jiao/Giao Region 交州, as the area was also known, Kiernan cites page 32 of Edward H. Schafer’s 1967 work, The Vermilion Bird: Tang Images of the South, to say that “Historian Edward Schafer has speculated that the first Chinese name for the region, Jiao, may be the same word as jiao (crocodile, dragon).” (38)

On that page, however, Schafer does not talk about Jiao region. Instead, he has a passage about the main Chinese administrative center in the region, Long Biên 龍編, where he says “The old name Long Biên means Dragon Twist, and is said to have been given to the place in the dim past because of a jiao dragon which coiled in the river near the newly founded city.”

That story comes from the Shuijing zhu 水經注 (Annotated Classic of Waterways) and is about an event that took place in 218 CE. The “jiao dragon” in this story that Schafter mention is jiaolong/giao long: 蛟龍. The “jiao/giao” 蛟 in this expression is different from the “jiao/giao” 交 in Jiaozhi/Giao Chỉ or Jiao/Giao Region.

The name “Jiao” for a place in the south is much older, and is not related to crocodiles or dragons.

One could go on and on and on like this, but I hope I have made my point over the course of these posts.

When manufacturers produce a product that is defective, they issue recalls.

This book is completely defective. It does not meet even the most basic scholarly standards.

Oxford University Press should issue a recall.

This Post Has 5 Comments

This is just outrageous.

Was this publication “peer reviewed”? I wouldn’t be surprised if it was because I’ve read other kooky “translations” of poetry/prose in “peer-reviewed” publications that are just a hair above Google Translate quality. I won’t publicly reveal the name of the author since his output is otherwise solid, but I was reading a translation of some very basic luc-bat meter writing (it isn’t even poetry, more like rhymed prose) within an academic essay published by a highly respected university in Vietnamese studies – I don’t even know how the translator got some of his ideas.

I wonder, what does it say/imply when, compared to major publications, blogs and Facebook are more active/relevant/accurate sources of current Vietnamese scholarship?

Totally agree. This book should be recalled immediately.

khoai2tra, you’re comments lead to a big issue, one that would take pages and pages to fully address. Yes there was apparently one outside reviewer (definitely not sufficient for a book that covers 2,000+ years of history), but it was read by other people whom the author knows as well, and it was published by a reputable press. So how does something like this happen?

The field of Vietnamese history in the English-speaking world is much stronger today than it was say 20 years ago, but by comparison to many other fields, it is still has many weaknesses. There are people in established positions who do not have the expertise and (linguistic) skills that they should have. There are many publications (particularly the pre-1990 works that Kiernan relies heavily on but later ones as well) that are problematic.

Meanwhile, the same conditions exist in Vietnam. There are people in established positions who do not have the expertise and (linguistic) skills that they should have and there are many publications that are problematic.

This doesn’t mean that it is impossible to produce solid scholarship on Vietnamese history. One just has to be careful. More importantly, however, one needs to be AWARE. One needs to be aware of one’s own limitations and of the limitations of other people.

I’ve been thinking about that and wondering how to get other people to realize that. Linguistic competence is one way (and that is a skill that is lacking among some people in the field), because as your example of identifying an established scholar’s poor understanding of basic luc-bat meter writing indicates, you are aware of that scholar’s limitations, but that scholar, is not aware of his/her own limitations.

That said, while linguistic competence is essential, there is probably more that is needed as well.

Nonetheless, in some other fields there are enough people who have the skills and awareness that the scholarship that is produced ends up being basically solid. The fields of premodern Chinese history and religion, for instance, seem solid to me. I have not come across works from those fields that are as weak as some of the pieces that have been published on similar topics in Vietnamese history/religion.

I think a big problem is that there are people who are not aware that the field of Vietnamese history has major weaknesses and treat it as if it was as solid as some fields that actually are quite solid. They see a famous name and assume that that scholar’s scholarship must be solid. That is an assumption that cannot always be made for the field of Vietnamese history.

That said, this does not mean that there is no hope. Christopher Goscha’s new survey of Vietnamese history is a perfect example of what is possible if one is aware, knows who else is aware, and takes the advice of people who are aware.

Did you send your comments regarding the book to Oxford University Press? Or a discussion forum for Vietnamese History, if there is one! I believe your blog is widely read but I don’t know how many “historians” read it.

Also, although the book may have may factual errors, is it good/usable in other ways? If that is the case, can the author/publisher simply send out some notice acknowledging the errors so to make the readers aware of the problems? And perhaps lower the price or give partial refund to the buyers? Seems like the right thing to do instead of recalling the book.

Speaking from a consumer’s point of view!

Thanks for the comments!

Historians don’t “comment” on this blog much, but they read it. This blog usually gets about 200 views a day, but since posting about this book it has been getting 400-600 views a day. Whether or not anyone at Oxford UP is aware, I suspect someone is, but I also suspect that an issue like this one is very complicated and sensitive for a press, so I’m happy to stay at a distance and let them figure things out on their own.

As for whether or not anything can be “saved” from this book, my sense is that the answer is a pretty clear “no.” It’s not just a matter of there being some factual errors. There are conceptual and methodological problems as well (and in my posts on this book that’s what I tried to point out). The information that the author attempts to provide is outdated. The list goes on and on.

That said, I haven’t looked at the parts on the colonial and post-colonial eras, but some people who have read those parts tell me that they suffer from the same kinds of problems that I pointed out for the first chapter.