I’ve said it a million times before, but I’ll say it here again: “It is impossible to understand pre-20th-century Vietnamese history if one does not read classical Chinese.”

I just came across an example of a single sentence that demonstrates this point perfectly (see the previous post for a detailed discussion of the passage where this sentence comes from).

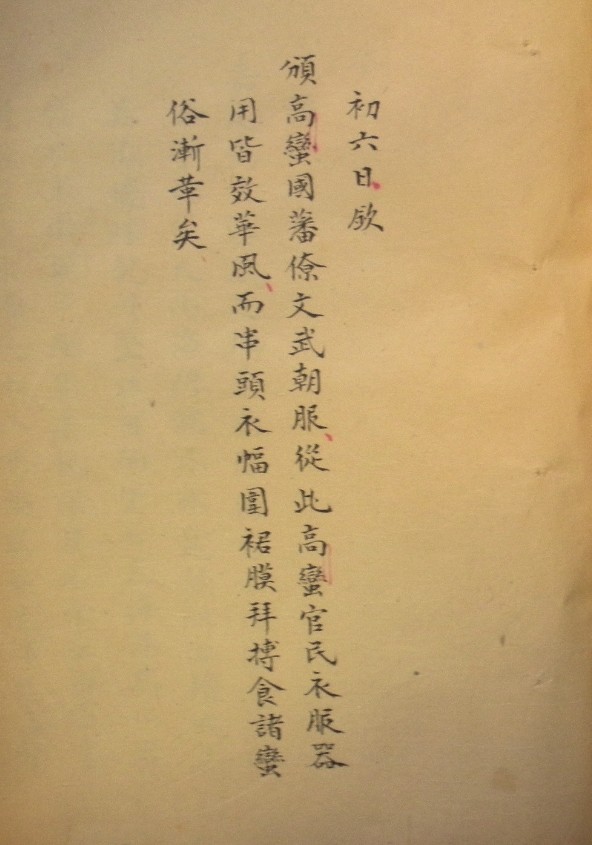

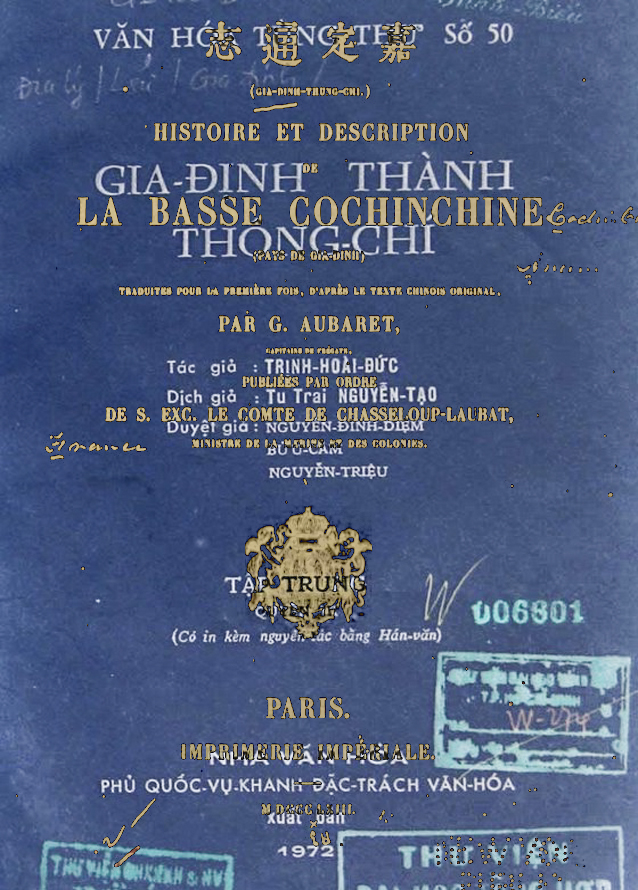

In the early nineteenth century, Nguyễn Dynasty official Trịnh Hoài Đức wrote in his Gia Định thành thông chí (嘉定城通志; Comprehensive Gazetteer of Gia Định Citadel) that in 1816 Cambodian officials were given robes by the Nguyễn Dynasty court to wear during ceremonies with Nguyễn officials and that:

“From this point onward the Cao Man officials and people all emulated the Hoa style in their clothing and utensils.”

[從此高蠻官民衣服器用皆效華風。]

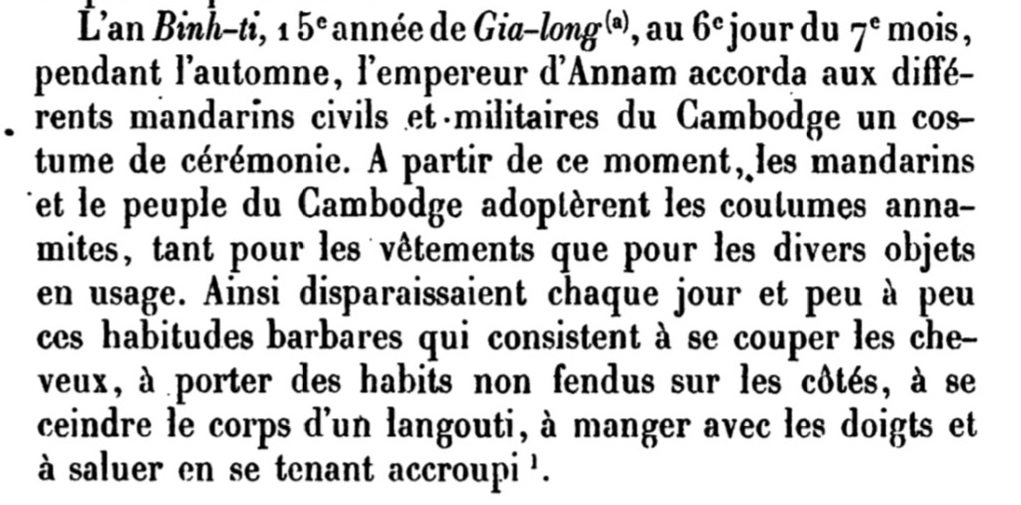

In 1867, French official Gabriel Aubaret translated this same line into French as follows:

“From then on, the mandarins and the people of Cambodia adopted Annamite customs, both in terms of clothing and objects of use.”

[A partir de ce moment, les mandarins et le peuple du Cambodge adoptèrent les coutumes annamites, tant pour les vêtements que pour les divers objets en usage.]

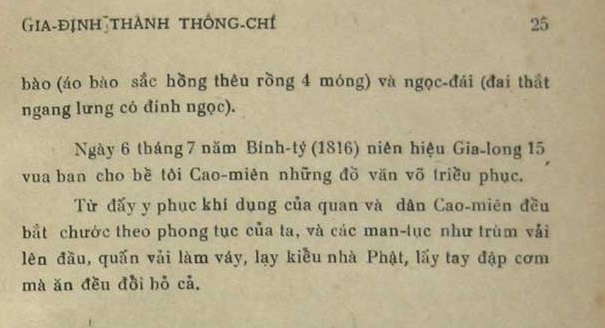

Then in 1970 Nguyễn Tạo translated this same line into modern Vietnamese as follows:

“From this point onward the Cao-miên officials and people all followed our customs in their clothing and utensils.”

[“Từ đấy y phục khí dụng của quan và dân Cao-miên đều bắt chước theo phong tục của ta.”]

Trịnh Hoài Đức wrote about “Cao Man” (高蠻) officials and people following the “Hoa style” (Hoa phong 華風).

Gabriel Aubaret wrote about the mandarins and the people of “Cambodia” following “Annamite customs.”

Nguyễn Tạo wrote about “Cao-miên” (高棉) officials and people following “our customs” (phong tục của ta).

These three sentences do not mean the same thing. The sentences in French and Vietnamese both distort what was originally written in classical Chinese.

Trịnh Hoài Đức lived in the premodern East Asian world where the elite (be they Vietnamese, Korean or Chinese) saw a divide between “Hoa” (華), or “civilized people,” and “Di” (夷) and “Man” (蠻), or “Barbarians” and “Savages.”

The name for “Cambodia” that Trịnh Hoài Đức used at that time contained the character for “savage” (the “Man” in “Cao Man”), as Cambodians were perceived by elite Vietnamese at that time to be on the other side of that Hoa-Di/Man divide.

What made someone “Hoa”? One was “Hoa” if one participated in the elite cultural world of East Asia (i.e., this was a “transnational” concept). This included wearing certain kinds of robes, reading and writing classical Chinese, following the teachings in the “Confucian classics,” etc.

Gabriel Aubaret, meanwhile, lived in a world of nation states and did not understand the ways in which Trịnh Hoài Đức was referring to a civilizational difference between “Cao Man” and the “Hoa” world. Instead, he transformed these distinctions into “national” distinctions: there were “the people of Cambodia,” and there were “Annamite customs.”

Finally, Nguyễn Tạo grew up in a Vietnam that had been transformed through its contact with France and where people now saw “national” distinctions as important, rather than “civilizational” distinctions like their ancestors had.

This emphasis on national distinctions meant that one’s nation was indeed supposed to be distinct. The term “Hoa” that Trịnh Hoài Đức used, however, was the same term that was used to refer to “China”. . . so Nguyễn Tạo changed “Hoa style” into “our customs.” That fit better with a nationalist view of the past.

“Cao Man,” meanwhile, was too derogatory (nations are distinct, but they still need to get along together), and he therefore used the term “Cao Miên” that had come into use during the colonial period as a neutral term for Cambodia.

As such, if one can read the original classical Chinese, one can see why Aubaret and Nguyễn Tạo wrote what they did.

At the same time, one can also see that Aubaret and Nguyễn Tạo did NOT translate what Trịnh Hoài Đức wrote. Instead, they both created something new.

This is one example of something that we can find happening over and over and over and over in modern Vietnamese (and other language) translations of Vietnamese historical sources that were originally written in classical Chinese.

So let me say it one more time: “It is impossible to understand pre-20th-century Vietnamese history if one does not read classical Chinese.”

This Post Has 2 Comments

We will encounter limitations as we try to dig into our past and cannot read at least tieng nom. How do you fair with your tieng nom? I have discovered your blog today, it is so dense it slows down my laptop. But a big thumbs up to you. I wish to know my Truyen Kieu. I have a copy of Mr. Huynh’s translation. I originally hail from Montreal, born and raised. I also volunteer in producing community performances that are inter-cultural, inter-disciplinary and inter-sectional, here in British-Columbia, Canada. I am also an MFA graduate from the Actors Studio Drama School in NY. I wish to further browse the material herein, eventually. I am glad you have this blog available. Thank you!!!

Nice to meet you!!

My knowledge of Nom is not that good. I can slowly go through a text with the help of a dictionary, but even then I will still have questions at the end. If you know Hán and you are a native speaker of Vietnamese, then I think it is easier to learn Nom as you have a good ability to guess. I know Hán, but I’m not a native speaker of Vietnamese, so in reading Nôm I don’t have that ability to guess.

It’s like this. Imagine seeing in a text “Mon tre ??” If you know English/French, you can easily guess that the ?? is “al”, but if you don’t know English/French, then you have to look in a dictionary to try to figure out what this means.

There are scholars in Vietnam (at the Vien Han Nom, for instance) who are very knowledgeable, and who can tell you, for example, exactly when and where it was written based on the characters used. I really admire people like that!!

As for the slowness of the website, I think that has more to do with the web host (Bluehost). I’ve also noticed that it has gotten really slow recently. I’ll try to figure out what is going on.