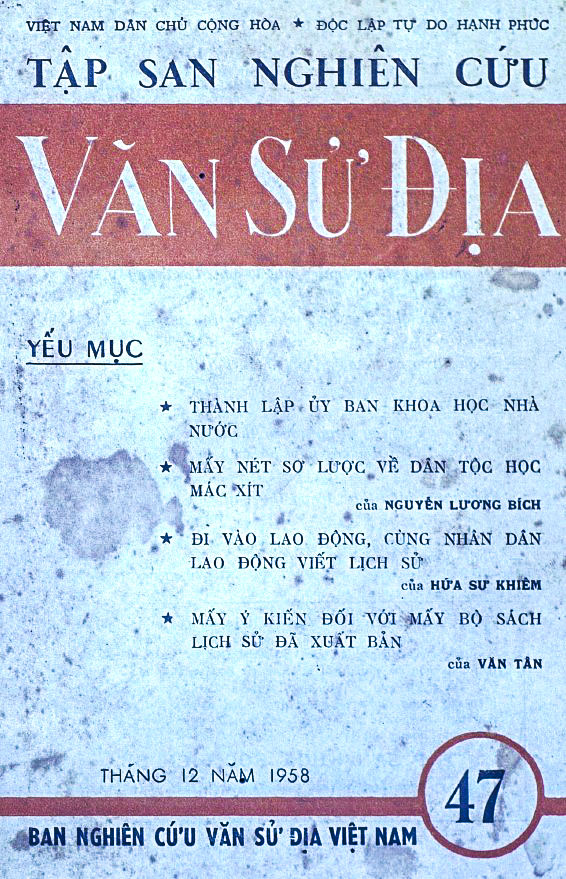

In 1958, North Vietnamese scholar Văn Tân published an article in the journal Văn Sử Địa entitled “Contributing to the Building of a General History of Vietnam – Some Views Regarding Some Published History Books” (Để góp phần xây dựng quyển thông sử Việt Nam – Mấy ý kiến đối với mấy bộ sách lịch sử đã xuất bản).

At that time there was a government-sponsored effort underway in the North to produce a new, and official, history of Vietnam. The goal was to produce a history that was based on scientific theory (which in this case meant Marxist theory), so as to move beyond the biases of earlier historians who had lived and worked in feudal (meaning “traditional” or “premodern”) and colonial societies.

In this article Văn Tân reviewed two history books that had been published a few years earlier: Minh Tranh’s Draft Brief History of Vietnam (Sơ thảo lược sử Việt Nam) and Đào Duy Anh’s History of Vietnam (Lịch sử Việt Nam). His purpose in doing so was to help historians understand what exactly a new history should look like, and at the end of his review he lists some points for historians to keep in mind as they engaged in the task of creating a new history for Vietnam.

At the same time, however, something else was going on in this article. Although it purported to be a “book review” and an “exchange of ideas,” Văn Tân clearly had an additional motive in writing this piece, and that becomes evident immediately in the opening passage of the article.

Văn Tân begins by noting that the people in North Vietnam were engaged in the process of building a socialist society, and he pointed out how important the teaching of national history was for that task. He also noted that in order to build this new society, people needed to have a deep sense of class consciousness (ý thức giai cấp), and to firmly grasp a class standpoint (lập trường) and viewpoint (quan điểm).

He then states that:

“Facts have proven that the Nhân văn – Giai phẩm saboteurs [bọn phá hoại] are not only opponents of the socialist revolution [bọn chống cách mạng xã hội chủ nghĩa], but are also degenerates [bọn trụy lạc] who are undisciplined in their actions.

“When the Nhân văn – Giai phẩm gang determined to transform schools into fortresses for opposing the regime, and to break schools away from the leadership of the Party, this was partially because they saw that our schools are the most negligent in teaching about class consciousness and forging a class standpoint, and to a certain extent it said that we have been negligent in teaching about the history of the nation.”

What on earth did this have to do with “some views regarding some published history books”?

The term “Nhân văn – Giai phẩm” in the above quote refers to the Nhân văn – Giai phẩm Affair. To simplify a very complex series of events, essentially what happened was that after the First Indochina War ended in 1954, various intellectuals, authors and artists in North Vietnam urged the government to ease up on certain intellectual and artistic restrictions that had been imposed during the war angst France.

The government did not agree to this. Instead, it punished those who were the most vocal in asking for these changes.

One person who had called on the government to ease its control of the work of intellectuals was one of the historians whose work was discussed in this article – Đào Duy Anh.

Needless to say, Văn Tân, a scholar who did not support the Nhân văn – Giai phẩm movement, seriously criticized Đào Duy Anh’s scholarship in this article.

But was Đào Duy Anh’s scholarship really “bad”? Or was this a case of the politicization of scholarship? Or perhaps it was a mixture of the two?

There is a good book on the effort of historians in North Vietnam in the 1950s-1970s to create a new history – Patricia Pelley’s Postcolonial Vietnam: New Histories of the National Past (Duke University Press: 2002). However, that book does not examine how the Nhân văn – Giai phẩm Affair affected the work of historians at that time, but as Văn Tân’s denunciation of Đào Duy Anh’s scholarship indicates, it clearly did.

Then there are several good studies of the Nhân văn – Giai phẩm Affair (Georges Boudarel, Peter Zinoman, etc.), however those studies have so far tended to focus on the influence of the Nhân văn – Giai phẩm Affair on the lives and work of authors and artists, rather than historians.

In the blog posts that follow we will try to get a sense of how the Nhân văn – Giai phẩm Affair did in fact have an impact on the production of historical scholarship in North Vietnam.