Ok, I know Wikipedia is not “scholarship,” but I’m going to use it to talk about scholarship anyway, because I just read an entry on the Vietnamese version of Wikipedia which nonetheless reminded me of a phenomenon which I commonly see in Vietnamese historical scholarship.

I was looking at the entry on “Wet Rice Civilization” (Văn minh lúa nước), and it says the following about the “quê hương” of wet rice civilization:

“Các nhà khoa học như A.G. Haudricourt & Louis Hedin (1944), E. Werth (1954), H. Wissmann (1957), Carl Sauer (1952), Jacques Barrau (1965, 1974), Soldheim (1969), Chester Gorman (1970)… đã lập luận vững chắc và đưa ra những giả thuyết cho rằng vùng Đông Nam Á là nơi khai sinh nền nông nghiệp đa dạng rất sớm của thế giới. Quê hương của cây lúa, không như nhiều người tưởng là ở Trung Quốc hay Ấn Độ, là ở vùng Đông Nam Á vì vùng này khí hậu ẩm và có điều kiện lí tưởng cho phát triển nghề trồng lúa.”

So this passage cites a long list of scholars (nhà khoa học) who have put forth a series of theories which hold that Southeast Asia is an area of the world where various forms of agriculture appeared quite early, and that contrary to popular belief, wet rice was not first cultivated in China or India, but in Southeast Asia.

So what is wrong with this entry? First of all, what year is it? It’s 2012. When does the scholarship in this entry date from? 1944-1974.

So have scholars really learned nothing new since 1974?

In fact, they have. Some have argued, for instance, that there is no evidence to support the ideas of scholars like Soldheim and Gorman mentioned in this entry.

Take a look, for instance, at what Ian C. Glover and Charles F. W. Higham, two mainstream academic archaeologists, wrote in the book The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia in 1996:

“Study of the origin and spread of rice cultivation in Southeast Asia has been characterized more by speculation than rigorous analysis. Gorman (1977) speculated that rice was among the earliest plants to be domesticated in the region, but his own and others’ archaeological evidence provides no support for this hypothesis.” (p. 419)

They also state that “Speculation on early agriculture in this region began with the excavation of Spirit Cave and Non Nok Tha (Solheim 1972). The former, a small rockshelter perched on a hillslope, was in fact a temporary base for foragers. The latter has, at last, an internally consistent chronology based on AMS radiocarbon dating of rice chaff from pottery temper, and it belongs to the later second millennium bc. Neither site has any relevance to the question of agricultural origins.” (p. 419)

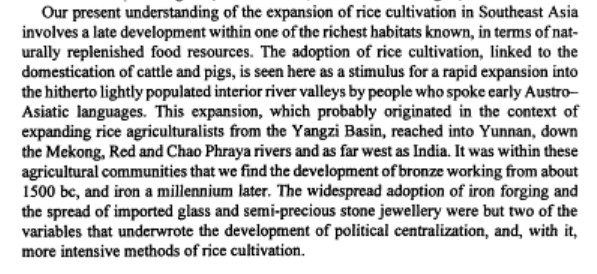

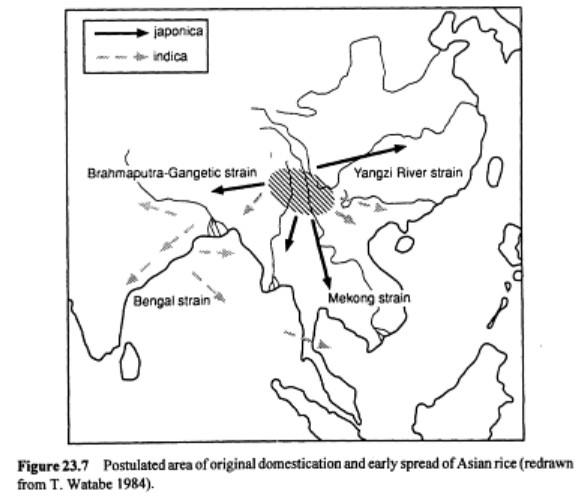

They go on to say that “Our present understanding of the expansion of rice cultivation in Southeast Asia involves a late development. . . which probably originated in the context of expanding rice agriculturists from the Yangzi Basin, [who] reached into Yunnan, down the Mekong, Red and Chao Phraya rivers and as far west as India.”

What does this have to do with “real scholarship”? In actuality I find that the selective citing of Western scholars, which can be seen in this Wikipedia entry, is also very common in Vietnamese historical scholarship (this may be less the case in some other fields). I see people citing the ideas of Western scholars which fit their own, even when those ideas have long been discredited in the West.

In part this might be because scholars don’t know what current knowledge about certain issues is in the West. Or it might be because their scholarship is driven by other motives than to be “khoa học.” Tôi không biết.

This Post Has 5 Comments

There are many things can be talked about VNese Historical scholarship at the moment and such two points you come across, using the old-fashioned references and selected quotations that only perfectly fit for a certain scholarly purpose.

The later I think, can be more or less found in different scholarships in other countries in which undoubtedly, nationalism is among powerful driven forces.

Interestingly, some foreign scholars who focus on Vietnam also fall in the same line as Liam C. K points out elsewhere, many have selected their favour Confucian quotes and seem to overlook the others.

However, I could not disagree that using out-of-date reference is the de facto main challenge for Vietnamese historical scholarship ( i would say in the field of history and political science). During my B.A. study, people has talked about nationalism almost every day, but no one mentioned Ben Anderson but J. Stalin, talked about Peasant economy and forms of struggle with out any idea of James C. Scott or Samuel L. Popkin,

In the field of SEA His., what you come across above is total amount of knowledge for most scholars to use in their university’s lecturers, no more and no less although in fact, they had no chance to read the original works, rather than to acquire unsystematically through Russian works. The latest book (only one, as far as I am concerned) in this collection is Stephen Oppenheimer’s Eden in the East. Part of the reasons can be, it fits quite well with our scholarship expectation and most importantly, it was translated into Vietnamese and by this mean, It can be read by academic community. No idea of Ian Glover, Robert Blust, Peter Bellwood, C. Higham, and most recently, Jared Diamond.

Most of textbooks of SEA His., are simply written based on French scholarship between 1944 and 1968. Thank to DGE Hall’s A History of SEA, right after being translated into Vietnam, this indispensable book have become the main source for any books, thesis, and dissertation in this field. Recently, 2008, G. Coedès’ Histoire ancienne des etats hin- douises d” Extreme-Orient was translated into Vietnamese, 64 year after it first came out in very Hanoi. So there have been now two bibles available for scholarship. No idea of Wolters, Wyatt, Chandler, Thongchai, Woodside, Whitmore, D. Marr, Cambridge HSEA, Tarling, Reid, J. Scott, Taylor, ect.

That is truly another world and do not know what to do with this.

Em cũng không biết.

Thanks for these comments.

Your mentioning “Eden in the East” brings up another point, which is that people sometimes also aren’t aware that just because something is published in the West doesn’t mean that it is considered to be legitimate scholarship. I don’t think any mainstream academic takes Oppenheimer’s book seriously. Even though he has some kind of connections to a university, he is not a trained academic, and his book is not, as far as I know, taken seriously by archaeologists, historians, etc.

It’s more popular “pseudo-science.” But, yea, it’s like a new bible to some people in Vietnam.

Thank you.

Comments like this will be a great help for local scholarship. Please keep track and hope you can come closer to the contemporary academic works, by this, it is hoped that people could achieve a better consciousness of where they are? and where do they go from here?

BTW, as you touching upon Oppenheimer, just wonder if you have come across Gavin Menzies, 1421: The Year China Discovered the World.

I read it, though truth be told that sources are not that much for the claim. Looking for some experts’ comments, including G. Wade (NUS), the feeling is that it also is not seriously taken by academia. From Chinese sources’ perspective, could you say something about it? I know that after the reign of Yongle, many documents had been burn down because of political intrigue. Thanks.

Yea, that book and Oppenheimer’s are in the same category. They are not taken seriously by academia. I haven’t read any Chinese sources about the Zheng He voyages. I would trust what Geoff Wade has to say about this issue.

As for “contemporary academic works,” if there is something you want me to look at, cu noi di.

I knew you had delivered a speech elsewhere about early Vietnamese Geography. Could I bring your attention to two specific moments of history: 15th and 19th century.

1. How you analyse Vietnamese geographical and geo-political consciousness in those times? Let say, e.g: its talked about space of ethnics? space of political entity? Nation state?

2. What is the difference or changes you see between 15th and 19th century-documents?

As Monoki Shiro (in Southeast Asia in the 15th and the China factor) coming along those 15th-documents and suggests of idea of “Geo-body” (the term Thongchai Winichakul uses for late 19th century Siam). Is it possible?

3. On the other hand, Kathlene Baldanza, Bradley David give idea of Ambiguous geographical awareness of the 17-19 century Vietnam through examining the Sino-Vietnamese borders. Do you think it was that much ambiguous? Chronicles between 15 and 19 show that Vietnamese had a strong, clear voice about the border with China (and since 1802, with Cambodia as well).

Many thanks.