I’ve long had a problem with the general narrative about the history of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Vietnam. Over and over you read in books that the Nguyễn Dynasty failed to deal with the French, and as a result of this, the “old world” of traditional Vietnam, and classical Chinese, died and the “new world” of reformers and revolutionaries like Phan Bội Châu took over, and that led to the Tonkin Free School in 1907 where vernacular Vietnamese written in quốc ngữ was promoted, etc. and. . . that’s the end of the story, as that road all leads to 1945.

What’s wrong with this narrative? First of all, Phan Bội Châu spent very little time in Vietnam in the early twentieth century, and his writings were not published at that time, so how could he have been influential?

Second, all of those people from the “old world” who were educated in classical Chinese and who studied for the civil service exam (which continued to be held until 1919) didn’t just “disappear.” They were the educated elite in Vietnam at that time. They must have played an important role. What was that role and why haven’t historians written about it?

To take the second part of that question first, the reason why historians have not written about this is because these members of the educated elite in early-twentieth-century Vietnam continued to write in classical Chinese, a language which most historians of modern Vietnam cannot read, and as a result, the historical records that this group of people left behind have been largely left unread.

As for the role of the “traditionally-educated” elite in early-twentieth-century Vietnam, I would argue that it was members of this group of people who were the true revolutionaries of modern Vietnam, because they were the ones who changed the way Vietnamese think. While people like Phan Bội Châu were living in exile, members of this group of people were hard at work transforming Vietnamese society.

A great example of this is a man by the name of Phạm Quang Sán. Born in 1874, Phạm Quang Sán passed the provincial exam in 1900 and then went on to serve as an official for the Nguyễn Dynasty in various capacities and various places in northern Vietnam over the next couple of decades.

At some point in the early twentieth century, Phạm Quang Sán also learned a lot about the West, and about Western knowledge. What is more, he sought to share that knowledge with literate Vietnamese by publishing small books that introduced new ideas.

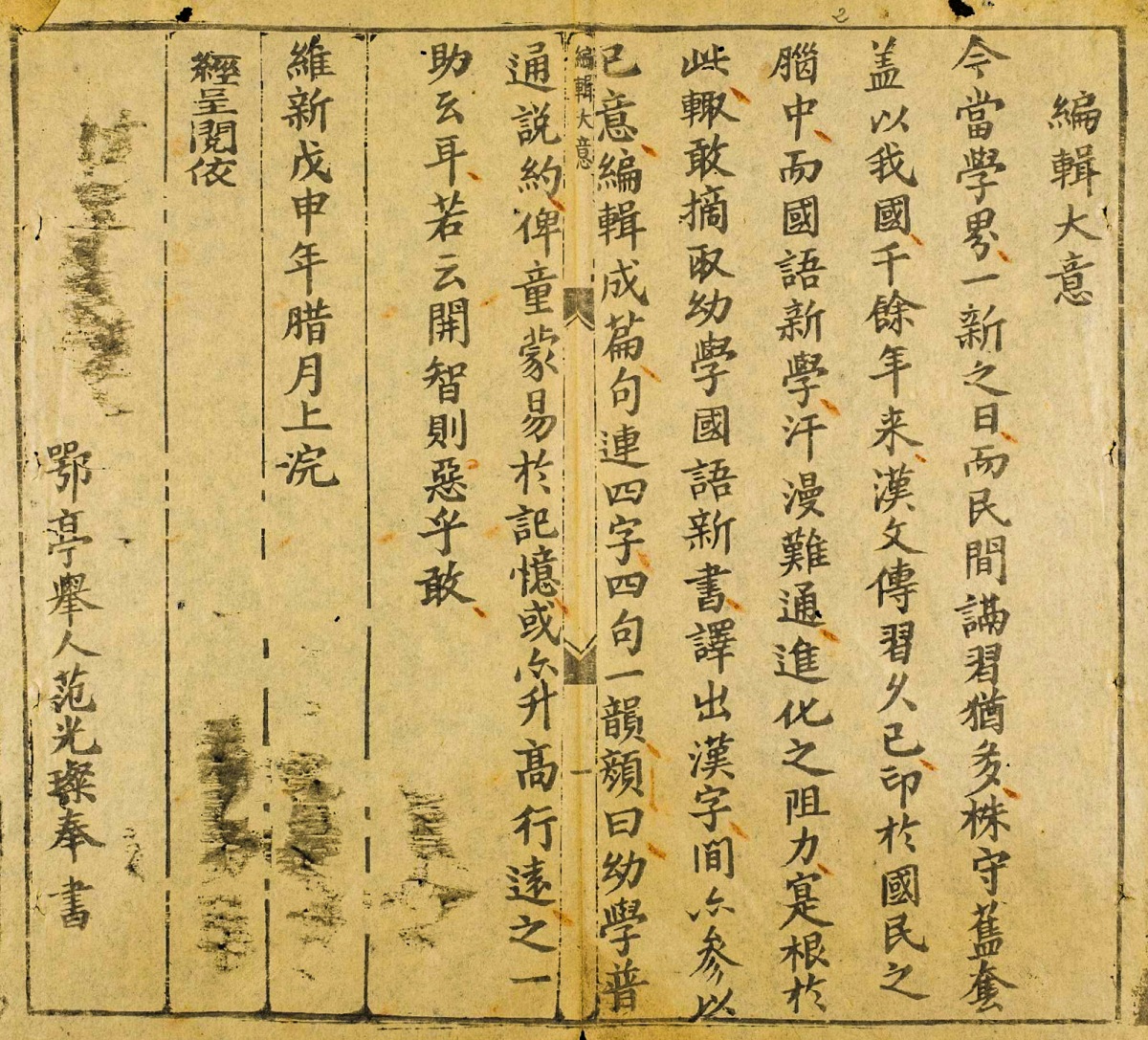

In 1908 Phạm Quang Sán published a book called the General Discussion of Elementary Learning (幼學普通說約 Ấu học phổ thông thuyết ước).

He explained the purpose of this book as follows:

今當學界一新之日,而民間講習,猶多株守舊套。蓋以我國千餘年來,漢文傳習久已,印於國民之腦中,而國語新學汗漫難通,進化之阻力,實根於此。

“At present in this new age of scholarship, teaching among the people still follows the stale old ways. This is because in our kingdom for more than a thousand years now Chinese characters have been passed down and are imprinted in people’s brains, so it is difficult for the spread of quốc ngữ new scholarship to break through. The force obstructing progress has its roots in this.”

In other words, what Phạm Quang Sán was saying was that although there were new ideas that were being promoted through the use of a new script, quốc ngữ, many people couldn’t read that script, and were continuing to study classical Chinese.

So what did Phạm Quang Sán do? He translated a book that was originally written in quốc ngữ – the New Writings in Quốc Ngữ on Elementary Learning (Ấu học quốc ngữ tân thư 幼學國語新書) – into classical Chinese and added his own comments so that people who did not know how to read quốc ngữ could learn the new ideas in that text.

And what kind of ideas were in that text? Well, new ideas about things like nationalism. After talking about the “five (Confucian) relationships” (father-son, king-officials, husband-wife, older brother-younger brother, friend-friend), for instance, the text goes on to say that “the clan and the society are all our compatriots who unite together to love the country/nation/kingdom.”

(親族社會,皆吾同胞,合群愛國。)

That’s modern nationalism, and nothing like that was expressed in Vietnam prior to the twentieth century. Now these concepts are as “imprinted in people’s brains” as Chinese characters were at the time that Phạm Quang Sán published his text.

A year later, in 1909, a few other Nguyễn Dynasty officials compiled another work in classical Chinese called the New Writings in Classical Chinese on Elementary Learning (Ấu học hán tự tân thư 幼學漢字新書).

What this shows is that while the familiar narrative of modern Vietnamese history talks about the emergence of reformers who started to use quốc ngữ, there were members of the Nguyễn Dynasty who translated those new texts into classical Chinese, as that was still the language of the literate elite at that time.

What is more, these Nguyễn Dynasty officials, like Phạm Quang Sán, all did this while “national heroes” like Phan Bội Châu were far away from Vietnam and essentially doing nothing that could effectively help change Vietnamese society at that time.

So when it comes to revolutionaries, who was truly revolutionary? Phan Bội Châu spent most of his “revolutionary” life outside of Vietnam and out of touch with Vietnamese society. Phạm Quang Sán, on the other hand, worked hard to introduce nationalist ideas into Vietnam.

Meanwhile those Nguyễn Dynasty officials who were “on the ground” in Vietnam, like Phạm Quang Sán, and who made the effort to transform educated Vietnamese in the most effect way at that time – through classical Chinese – why don’t we consider those people revolutionaries?

How many of the people who learned about “loving the nation” by reading Phạm Quang Sán’s published General Discussion of Elementary Learning ever read any of the unpublished writings of Phan Bội Châu?

This Post Has 14 Comments

I wonder what the earliest record of using 愛國 ái quốc for Vietnamese in that sense was? To use the word like Phạm Quang Sán does here is a true sign of adoption of modern nationalist ideas. 愛 Ái in the past had a meaning more like “cherish” and was a top down verb, so parents could ái their children, but their children couldn’t ái them back, as far as I have found. In a book of “Chinese New Terms and Expressions” (1912? I forget the precise date), ái quốc was in there in the sense of patriotism, and I believe it had been recent been borrowed from aikoku, the Sino-Japanese translation of the term patriotism. I did a search through the whole of the Sukuquanshu a few years ago to find whether or not this verb was used in premodern works, and found it was, but rarely, because the only person capable of top-down ái quốc was the emperor, who could ái quốc như gia 愛國如家 (love the country like it was his family). The rest of the people? They could be trung 忠 to the emperor, but they couldn never ái him.

I don’t recall PBC using ái quốc in the texts of his that I translated, but I may just have forgotten.

Thanks for pointing this out! That’s very cool that you looked through the Sikuquanshu for “ai quoc,” and your findings make sense. I had forgotten about the “top-down” aspect of “ai,” but your mentioning it brings back memories of learning that somewhere along the way. So thanks, that helps!!

合群, unite into groups, is also a key expression that dates from that time. You see it in the writings of Liang Qichao and other reformers. I’m not sure where exactly this comes from, but it must be from some nineteenth-century Western writing on the historical development of human societies (that then passed from Japanese into Chinese), but at this time in reformist writings there are various people who try to explain how humans form into larger and larger groups, from the family to the lineage, to larger groups 群, and finally into the nation.

That’s interesting. But I wonder why Phạm Quang Sán chose this approach. This book was for children who can equally well learnt Quốc ngữ or Chinese characters. This book might have taken up some precious time that they could use to read Quốc ngữ. Writing books for adults in Chinese would make more sense.

He did write books for adults too:

https://leminhkhai.wordpress.com/2016/11/03/pham-quang-sans-attempt-to-revolutionize-the-civil-service-exams-khoa-cu/

As for why he wrote this book in chu Han (classical Chinese), that’s what he explains in the part I quoted – people were stuck in their ways and did not want to switch to using quoc ngu, so PQS decided that if they were not going to learn quoc ngu then he would translate new ideas into classical Chinese.

I think it makes a lot of sense that people in general would be very conservative. Try to get members of the elite today to send their child to an new “experimental” school rather than an established school with a high reputation. Most of them will not do that.

Would everybody please say Latin letters or transcription and not chữ Quốc ngữ or quốc ngữ . Quốc ngữ in Vietnam means “vernacular or plain talk ; chữ Quốc ngữ is the latin transcription supposedly of quốc ngữ but it is a misnomer , it transcripts all forms of vietnamese , whether oral Quốc ngữ or written wenyan – văn ngôn ( 文 văn= beautiful , aesthetic ) or nôm or Han characters

I see your point, but a kind of custom has emerged, at least in writings in English, that uses the term “quoc ngu” in a certain way.

So, for instance, you will see people talking about “quoc ngu journals.” What does that mean? It means a journal in modern Vietnamese that uses the Latin alphabet to transcribe Vietnamese.

Why do people use the term “quoc ngu” there? Because it’s a lot easier to use 2 words than it is to say “in modern Vietnamese that uses the Latin alphabet to transcribe Vietnamese.”

I agree though that if you look at the actual words then “quoc ngu journal” is vague, but it is a convention that has emerged.

Thank you again for writing such an informative article. I wanted to mention that cu Pham quang San was born in 1877, and he did indeed write in Quoc-van. Cu Pham quang San is a distant relative of mine. I have our family tree (gia pha) and a section of Dong-ngac tap bien (writings on our village, Dong-ngac) if you would like to do more research. Thanks again!

Wow! That’s very interesting!! I only found one brief discussion about PQS on the Internet (see below), and that’s where I got the date of 1874 for his birth.

I haven’t started researching more background information about this topic yet. I just came across these documents, found them to be very interesting, and decided to write about them. Someday I’ll try to work this into an academic article, and if/when I do, yes, reading the Dong-ngac tap bien will surely be helpful.

Ngạc Đình Phạm Quang Sán – một nhà nho học nổi tiếng

Bản tin nội tộc (Số 8/2004), 01-05-2004. Số lần xem: 4690

Phạm Quang Sán hiệu là Ngạc Đình, sinh năm Giáp Tuất (1874), xuất thân từ một gia đình nho học, trong một dòng họ nổi tiếng có 9 Tiến sĩ và 2 Sĩ vọng Thời Lê, Nguyễn của làng Đông Ngạc (nay thuộc xã Đông Ngạc, huyện Từ Liêm, ngoại thành Hà Nội).

Cụ đỗ tú tài khoa Đinh Dậu (1897), đỗ cử nhân khoa Canh Tý (1900). Cụ đi dạy học ở phủ Quốc Oai (Sơn Tây) 10 năm, rồi lần lượt giữ các chức Huấn đạo, Trợ tá ở huyện Hưng Nhân (Thái Bình), Tri huyện các huyện Hải An (Kiến An), Tiên Lãng (Thái Bình), Thương tá ở tỉnh Phú Thọ, từ trần năm Nhâm Thân (1932).

Cụ là một nhà nho học uyên bác, khi dạy học có rất đông học trò, trong đó có nhiều người thành đạt. Cụ sáng tác nhiều văn thơ bằng chữ Hán, chữ Nôm và Quốc ngữ, có nhiều bài đăng trong các tạp chí Nam Phong, Hữu Thanh… và dịch nhiều sách truyện Trung Hoa ra quốc ngữ.

Sách Đông Ngạc tập biên của Dĩ Thuỷ Phạm Văn Thuyết có lược kê một số tác phẩm của cụ như sau:

A. Về Hán văn có: Phổ thông thuyết ước – Văn sách (quyền thượng và quyển hạ) – Đạo đức luận – Chấn chỉnh thượng trường vấn đề…

B. Về Quốc Văn có: Nam ngạn trích cổm – Phú cờ bạc – Phú phương ngôn – Hán học cách ngôn – Hiếu tử liệt truyện… và nhiều truyện dịch. Trong đó có nhiều tác phẩm còn được người đời truyền tụng như các bài Thơ khuyên hiếu, Phú cờ bạc, Phú phương ngôn mang đậm tính giáo dục tư tưởng và đạo đức.

Tuy xuất thân từ một gia đình nho học nhưng cụ vốn là một người giàu lòng yêu nước, nên rất có cảm tình với phong trào cách mạng. Theo bản “Hồi ký về việc liên lạc với các đồng chí cách mạng cũ thời kỳ thành lập Việt nam Thanh niên Cách mạng đồng chí hội” của Trần Đình Sóc (Viện Bảo tàng cách mạng Việt Nam) thì cụ đã từng góp 300 đồng làm lộ phí cho đồng chí Lê Hồng Sơn sang Quảng Châu hoạt động cách mạng là một số tiền rất lớn thời đó (1923).

Cụ xứng đáng được tôn vinh là một nhà nho trong sáng, một nhà giáo dục đạo đức mẫu mực, một tác gia đã để lại nhiều tác phẩm hữu ích cho đời sau.

Phạm Quang Đại

Đông Ngạc – Từ Liêm – Hà Nội

@rigor iron

quoc ngu/chu quoc ngu means national language/ national script. It is romanization using letters and diacritics via the Latinate Romance languages, to transcribe spoken Vietnamese by missionaries who have nothing better to do but proselytize a whole Buddhist country but still the vocabulary includes Mon-Khmer, Cham, Chinese(many dialects but mainly Fujianese, Cantonese, & Hakka), French, English, etc… it is NOT a misnomer. 文 doesn’t mean beautiful or aesthetic, it’s Chinese, not Vietnamese. văn ngôn / 文言 is Chinese not Vietnamese.

@bryan_ brouillon

_ you assert ” quoc ngu/chu quoc ngu means national language/ national script” then immediately you say it’s romanization , it’s contradictory ; if it’s latin script , it can’t be national . You should know that quoc ngu doen’t mean national speak but vernacular , plain talk. You admit , you’re a newcomer to Vietnamese , you should deepen your knowledge

– 文 has many meanings ; which dictionary do you read ? If văn ngôn / 文言 doesn’t mean

aesthetic , tell us what do you think it means ; văn ngôn / 文言 is not only chinese ; it’s a

written language formerly used by VN , Chinese ,Korean , Japanes literati When they met , unable to talk with each other , as was the case of Phan bôi châu in Japan , they used văn ngôn / 文言 to ” 筆 bút 談 đàm _ pinsel talk “

How come the latin transcription became known as chữ Quốc ngữ ..? I suppose in hindsight , it’s the mixing of two historical phenomenon , the decision to replace wenyan _ van ngôn by vernacular , plain talk in administrative matters and the repacement of Han characters by Latin alphabet

_ in full ,chữ Quốc ngữ = ” chữ La tinh phiên âm tiêng quốc ngữ ”

_ wenyan should be translated by the French words ” belles- lettres ” rather than classical or literary Chinese

I am Learnist here that nationalism is a recent concept. I wonder, in the saying attributed to Confusious: Tu than, Te Gia, Trị quốc, bình thiên hạ, what does “quốc” here really mean? Anyone can help me here?

Good question! The concept of nationalism doesn’t deny that “something” existed in the past, it just points to the ways in modern times that people have expanded/exaggerated/invented the concept of the nation for certain purposes.

As for that expression, think first about who it was directed at. Did universal education exist at that time, and were schoolchildren all reading this in school textbooks? No, that was a very elite concept for the elite members of society – people who either were or wanted to be government officials and for the king.

So it is from that perspective that we can get a sense of understanding about what that concept meant. Until constitutional monarchies started to appear in Europe a couple centuries ago, monarchs throughout history viewed their kingdoms as literally “THEIRS.” And the people in those kingdoms were their subjects, not their fellow citizens. The list of differences that we could come up with goes on and on and on.

When we consider all of those differences and think about the context in which that phrase emerged, we can see that what that passage is telling a monarch is something like this: “If you cultivate your morality, you will be able to keep the royal family in order, and you will be able to govern over Your kingdom, and to bring peace to the region [which means keeping your vassal kingdoms from rebelling].”

I hope that helps.

Thank you for your very enlightening reply.