One of the core tenets of Vietnamese ultranationalism is the idea that there is a fundamental division between Han Chinese and Vietnamese.

In particular, the argument of Vietnamese ultranationalism is that the Han Chinese were originally pastoral (du mục 遊牧) while Vietnamese from the earliest times have been agricultural (nông nghiệp 農業).

As any archaeologist knows, Han Chinese have been practicing agriculture for thousands of years, but the argument of Vietnamese ultranationalism is that before they started to engage in agriculture, the Han Chinese had originally been pastoralists, and that even though they eventually turned to practicing agriculture, many of their pastoral traits – such as a penchant for violence and for oppressing agriculturalists – nonetheless persisted.

In other words, to simplify the argument, the basic point here is “Han Chinese = bad, Vietnamese = good.”

While it is completely understandable that an ultranationalist argument would propose such a clear dichotomy of good vs. bad, it is more difficult to understand how anyone could get the idea that the Han Chinese were originally pastoralists and that pastoralists are somehow more violent and oppressive than agriculturalists.

In what follows, I will try to give a sense of how these ideas developed.

One of the first people to write in detail about this was South Vietnamese philosopher Kim Đình, and in putting forth his ideas, Kim Định cited the work of the American writer, Will Durant.

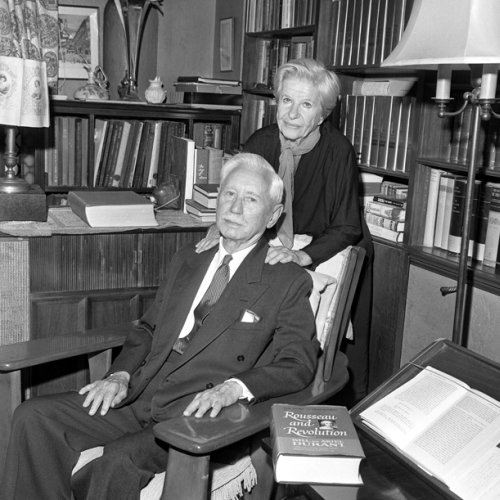

Will Durant was what we could call an “independent scholar.” Although he was trained in philosophy rather than history, over the course of several decades, from the 1930s to the 1970s, he published, in collaboration with his wife, an 11-volume series on “The Story of Civilization.”

While these books were never regarded highly by professional historians, they did popularize information about world history among the general public, albeit world history as seen from the perspective of the Durants.

In his 1973 work, Việt Nho Structure (Cơ cấu Việt Nho), Kim Định cited a French translation of the first volume of Durant’s series to support his explanation of the difference between pastoral and agricultural societies.

The term for “pastoral” in Vietnamese is “du mục,” where literally “du” mean “to move about” and “mục” means “to herd” or “to shepherd.”

This is significant for Kim Định as he sees the “moving about” of pastoralists as being tied to the world of hunting where people had to move about to find their food, whereas the “herding” was closer to the world of agriculture, as it required that one domesticate animals in order to be able to herd them.

The reason why this was significant for Kim Định was because he felt that this term symbolized the place of pastoralism in human history, namely that it was the last stage of hunting and gathering, and as such, it still carried with it many of the elements of the hunting lifestyle, such as bloodletting, violence and oppression.

These elements, Kim Định argued, persisted in such societies long after they turned to agriculture.

In other words, Kim Định’s logic was that 1) hunters are the most violent and 2) pastoralists maintain many elements of the hunting lifestyle, so therefore 3) when pastoralists become agriculturalists they remain violent and cruel.

Again, in making these points Kim Định cited Will Durant’s “The Story of Civilization,” but this is not at all what Durant argues in that book. [Kim Đình cites pages 36, 41 and 76 of the French-language addition. Pages 36 and 76 correspond to pages 7 and 52 of the English-language edition. However, I cannot find anything in the English-language version that corresponds to what Kim Đình says is mentioned on page 41 of the French-language edition.]

Instead, this is what Durant wrote:

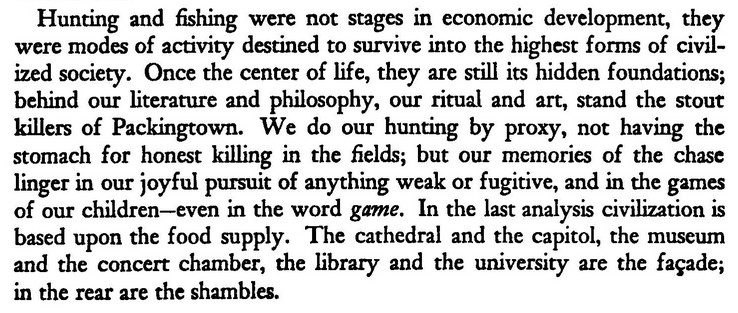

“Hunting and fishing were not stages in economic development, they were modes of activity destined to survive into the highest forms of civilized society. Once the center of life, they are still its hidden foundations; behind our literature and philosophy, our ritual and art, stand the stout killers of Packingtown [i.e., a working class area of Chicago].

“We do our hunting by proxy, not having the stomach for honest killing in the fields; but our memories of the chase linger in our joyful pursuit of anything weak or fugitive, and in the games of our children even in the word game. In the last analysis civilization is based upon the food supply. The cathedral and the capitol, the museum and the concert chamber, the library and the university are the façade; in the rear are the shambles.” (7)

In other words, Durant argued that the violence of hunters continued not only in the lives of pastoralists, but in the lives of EVERYONE, even “into the highest forms of civilized society.”

What is more, he did not portray the agricultural life as a clear improvement over earlier times, as he felt that agriculture brought many new problems to humankind. He argues, for instance, that “Agriculture, while generating civilization, led not only to private property but to slavery.” (19)

Finally, he did not argue that pastoralists were more violent than agriculturalists. Instead, the distinction that he made was between “primitive” and “civilized” man. The adoption of agriculture did not make someone immediately “civilized.” Instead, this is a process that took many centuries as it required the development of cultural practices that would control the violent nature of all “primitive” peoples, be they hunters, pastoralists, or agriculturalists.

As such, while Kim Định cited Will Durant’s work, Durant’s work does not support Kim Dình’s ideas AT ALL.

This distortion of Durant’s book was later continued by Trần Ngọc Thêm, the author of Searching for the True Nature of Vietnamese Culture (Tìm về bản sắc văn hóa Việt Nam) a popularly used textbook on Vietnamese society that is deeply indebted to Kim Đình’s ideas.

In that work Trần Ngọc Thêm cites Durant in arguing that the Han Chinese were originally pastoralists. He states that “The ancestors of the Han have pastoral origins that emerged from Central Asia. According to Western sources, or [sources] from the West, this matter is very obvious.” (62) He then cites a Vietnamese translation of the section on China in Durant’s first volume to support this point.

Let me cite that section at length because 1) it does not support what Trần Ngọc Thêm wrote, but 2) one needs to read the full passage to understand what Durant was saying. [It is on page 641-42 of the English-language version.]

“No one knows whence the Chinese came, or what was their race, or how old their civilization is. The remains of the ‘Peking Man’ suggest the great antiquity of the human ape in China; and the researches of Andrews have led him to conclude that Mongolia was thickly populated, as far back as 20,000 B.C., by a race whose tools corresponded to the ‘Azilian’ development of mesolithic Europe, and whose descendants spread into Siberia and China as southern Mongolia dried up and became the Gobi Desert. The discoveries of Andrews and others in Henan and south Manchuria indicate a Neolithic culture one or two thousand years later than similar stages in the prehistory of Egypt and Sumeria. Some of the stone tools found in these Neolothic deposits resemble exactly, in shape and perforations, the iron knives now used in northern China to reap the sorghum crop; and this circumstance, small though it is, reveals the probability that Chinese culture has an impressive continuity of seven thousand years.

“We must not, through the blur of distance, exaggerate the homogeneity of this culture, or of the Chinese people. Some elements of their early art and industry appear to have come from Mesopotamia and Turkestan; for example, the neolithic pottery of Honan is almost identical with that of Anau and Susa. The present ‘Mongolian’ type is a highly complex mixture in which the primitive stock has been crossed and recrossed by a hundred invading or immigrating stocks from Mongolia, southern Russia (the Scythians?), and central Asia. China, like India, is to be compared with Europe as a whole rather than with any one nation of Europe; it is not the united home of one people, but a medley of human varieties different in origin, distinct in language, diverse in character and art, and often hostile to one another in customs, morals and government.”

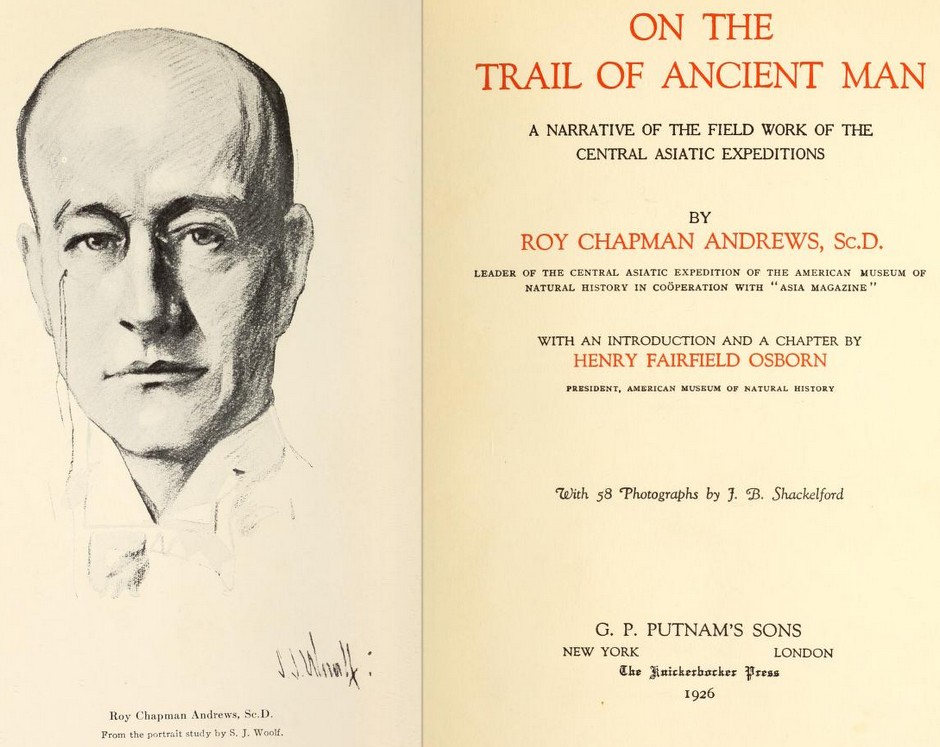

In contrast to what Trần Ngọc Thêm wrote, Durant did not say here that the Han “have pastoral origins that emerged from Central Asia.” Instead, he cites the 1926 work of Roy Andrews, the leader of a “Central Asiatic expedition” on behalf of the American Museum of Natural History, to argue the opposite, namely that Chinese had been living in the region for as long as anyone could tell, and that no one knew where they might have originally come from, or what their original society might have been like.

He did argue that like people in other parts of the world, such as Europe and India, the Chinese probably consisted of a “primitive stock” which had then intermixed with “invading or immigrating stocks,” but he did not say that any of these people were pastoralists, or that the Han Chinese were originally pastoralists.

Indeed, he didn’t say anything about pastoralism.

Will Durant was not an expert on Chinese history. As a student he studied Western philosophy, and from that background he went on to write a history of world civilization.

Kim Định and Trần Ngọc Thêm both cited his work to support their argument about a supposed cultural divide between pastoralists and agriculturalists in antiquity. In doing so, however, they completely distorted what Will Durant wrote.

The ideas of Kim Định and Trần Ngọc Thêm about a supposed cultural divide between pastoralists and agriculturalists are thus based on a “double failure.”

They both failed to build their ideas on the work of experts, and they both failed to even understand the ideas of the non-expert they did consult.

This idea that there is a cultural divide between pastoralists and agriculturalists therefore has no basis in reality. It is the product of ultranationalist imagination.

It is interesting, however, that this ultranationalist imagination has felt the need to cite Western scholars.

Those Western societies, after all, were also originally pastoral. . . weren’t they?

This Post Has 4 Comments

Really enjoying your insights, here and in general. This reminds me a bit, though reversed, of some of the ‘logic’ used from the Chinese side in the political-archaeological arguments over whether the Dong Son belonged to the Chinese or the Viet that I read a few years ago.

Thanks for the comment, and sure, that makes sense. Perhaps you read the article that Han Xiaorong wrote. There are a couple of versions of it, one in the University of Hawaii graduate student journal, Explorations, and then a revised version in the professional archaeological journal, Asian Perspectives, both of which I think are available online (the latter I think is available at Scholarspace at the University of Hawaii).

The one distinction, I think, is that the Chinese commentary represents a passing phase, whereas this Vietnamese perspective is a major and enduring obsession. One can find it repeated ad nauseam in Vietnam today.

Thanks .. its been nearly a decade, and something I found during other research. I’ll see if I can find it again at Scholarspace.

I’d argue both are reflections of the larger issues that have been around since the Ly and before, with the obsessiveness in turn a reflection of being on the cultural defensive. Regardless, your points are well founded.

You should also notice the view that Zhou people were regarded as pastoral (and of Western origin) vs Shang people as agricultural was once also popular among Chinese scholars and Western scholars in early XX century.