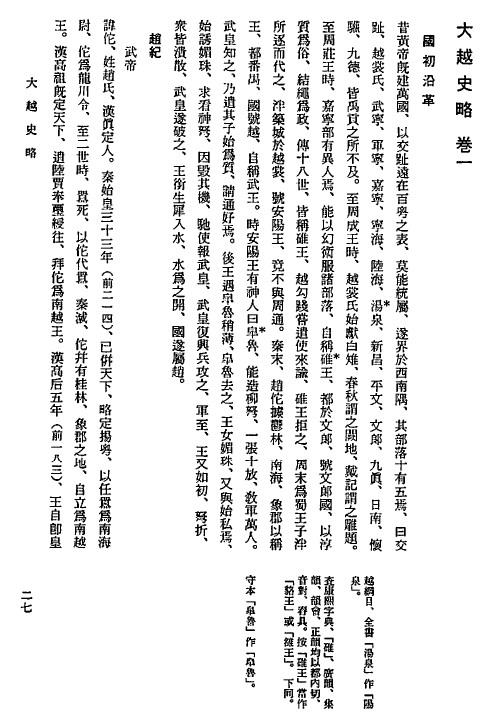

There is a text known as the Việt sử lược or the Đại Việt sử lược which was reportedly compiled in the fourteenth century. During the Ming occupation, it was brought to China where it was subsequently included in the Siku Quanshu.

In the twentieth century, this work was translated into quốc ngữ. Trần Quốc Vượng translated the work in 1960, and Nguyễn Gia Tường in 1972 (but it wasn’t published until 1993). Here is a passage from Nguyễn Gia Tường’s translation:

“During the time of King Zhuang of the Zhou, in Gia Ninh Region there was a extraordinary person who was able to use sorcery to bring into submission the various tribes. He called himself the Hùng King, established a capital at Văn Lang, and called [his kingdom] the Kingdom of Văn Lang. Customs were pure and simple, and tying knots was used for administration. Transmitted through 18 generations, all were called Hùng King.”

Đến đời Trang Vương nhà Chu (696-682 trước Công nguyên-ND)8 ở bộ Gia Ninh có người lạ, dung ảo thuật qui phục được các bộ lạc, tự xưng là Hùng Vương đóng đô ở Văn Lang, đặt quốc hiệu là Văn Lang, phong tục thuần lương chơn chất, chính sự dùng lối thắt gút. Truyền được 18 đời đều xưng là Hùng Vương.

What is so “evil” about this translation? It is the fact that the original version of the text that we have (the one preserved in the Siku Quanshu) does not contain the character for “hùng” in “Hùng King.”

Instead, it contains a character which is pronounced “đôi” (碓).

Yes, this character looks like the character for “hùng” (雄). But it also looks like the character for “lạc” (雒), which we find in earlier Chinese texts.

Indeed, when Chen Jinghe published a collated version of this text, he noted this issue, and stated that this “đôi” should be “lạc.”

So why is it “hùng” in a quốc ngữ translation? And why isn’t there a footnote indicating that the character in the original is “đôi”? Nguyễn Gia Tường added many footnotes to his translation. Why leave this one out?

This Post Has 2 Comments

I just want to have some naive notes:

1) “Nguyễn Gia Tường added many footnotes to his translation. ” So did Nguyen Gia Tuong add a footnote about this “evil” point?

2) You might want to double check the 影印版 version. Because it is not unusual that the digital version of the Siku Quanshu can produce typos.

3) Readers might need to know the history of different versions of the Viet su luoc texts transmitted in “Vietnam” and in “China.” What are the texts that Tran Quoc Vuong and Nguyen Gia Tuong read?

1. No. That was my point. Look at the image of that page. There is no footnote about that character/word.

2. Good point. I also used the collated version of this text which Chen Jinghe published in the late 1980s. It 以商務印書集成初編版“越史略”為底本 and he checked this against 文淵閣四庫全書“越史略”及守山閣叢書本“越史略”等書. So I think we can rule out the possibility that what we see in the digital version of the Siku Quanshu is a typo.

3. I have not seen TQV’s translation. If anyone has it, I would like to know what he wrote, and what version of the text he based his translation on. As for Nguyen Gia Tuong, this is the version of the text he said he translated:

Bản sao của bộ sử này có trong tủ sách cổ văn của Ủy ban dịch thuật thuộc phủ Quốc vụ khanh Đặc trách văn hóa, nó được giao cho chúng tôi dịch ra Việt ngữ từ năm 1972.

In other words, we have no idea what text he was using. So you bring up a good point. Whatever the text was that he was translating, it might have had the character for Hung instead of Doi.

HOWEVER, that leads to other problems. Namely that no one should ever publish a translation of a copy (bản sao)!!!!! That is totally unprofessional and unacceptable. There are “standard” versions of this text which people can access. Those are the versions which one should publish so that others can verify one’s translation.

Finally, I did not “discover” this issue. The fact that the DVSL has the character “doi” has long been known to scholars. It’s mentioned by someone in the Hung vuong dung nuoc books (Dao Duy Anh?). I think Rao Zongyi mentioned it in the 1960s. I seem to recall Ta Chi Dai Truong noting this somewhere. And it is there in the published versions of this text which have been around for years: a 商務印書館 publication from Shanghai in 1936 and a 藝文 from Taibei in 1968, etc.

Do Vietnamese historians today not know this? I was assuming that they did. I will be surprised/distraught if it is the case that they don’t.