Some of the earliest writings about the Red River Delta region were about its spirits. More specifically, they were about the appropriation of local spirits by the ruling elite.

This is a practice that we have clear evidence for from the period of the Tang Dynasty. At that time, an administrator by the name of Zhao Chang wrote a work in the early ninth century called a Record of Jiaozhou (Jiaozhou ji 交州記) that documented this phenomenon, and later in the fourteenth century, Lý Tế Xuyên compiled a text which also recorded information about the same phenomenon entitled Collected [Records] about the Departed Spirts of the Việt Realm (Việt Điện U Linh Tập 粵甸幽靈集).

Zhao Chang’s book is no longer extant, but it is cited at times in the Collected [Records] about the Departed Spirts of the Việt Realm, and it is also cited in an inscription that was inscribed on a bell at a Daoist temple somewhere between 1314 and 1324 known as the “Record of the Bell at Thông Thánh [Daoist] Temple in Bạch Hạc” (Bạch Hạc Thông Thánh quán chung ký 白鶴通聖觀鐘記) that was written by a Daoist master from Fujian who had taken up residence in the Red River Delta by the name of Xu Zongdao/Hứa Tông Đạo 許宗道.

This is how the inscription begins:

According to Master Zhao’s record [i.e., Zhao Chang’s Record of Jiaozhou], during the Yonghui era [650-655 AD] of the Tang, Ruan Changming served as protector general [military commissioner] of Phong/Feng Prefecture. Observing the vastness of the land, surrounded by mountains and rivers, he ordered that Thông Thánh [Daoist] Temple be constructed on the outskirts of Bạch Hạc and that statues of the Three Pure Ones [i.e., three Daoist deities] be placed inside to create a sense of majesty. He also ordered that two spaces be opened, one in front and one behind, where he planned to have statues of guardian deities of the temple created [and placed.] Unable to determine which deity was numinous, he burnt incense and incanted, “Whichever spirit here is numinous, reveal yourself so that I can create a statue in your image.

That night he dreamt that two peculiar men with gaunt faces arrived with their apprentices in tow, scolding and insulting each other, and proceeded to Changming’s Temple of Tranquil Residence.

Changming asked, “What are your names?” One was called the Earth Magistrate and the other was called the Stone Chief Minister.

Changming stated, “Whoever’s techniques are superior will reside in the front.” The Stone Chief Minister leaped over to a riverbank, but then suddenly saw that the Earth Magistrate was already there. The Stone Chief Minister leaped again to the other side of the river, but saw again that the Earth Magistrate got their first. The Earth Magistrate thereupon earned [the right to take the front position]. He has presently been invested as the Martial-Aiding Loyalty-Assisting Awe-Manifesting King.

From the Tang to the present, for centuries, his land has been divinely numinous, and prayers are fulfilled. Such has it been from past to present.

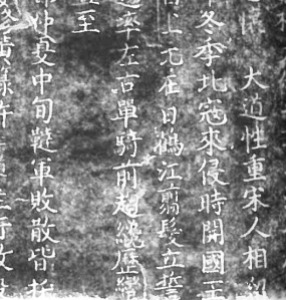

桉趙公記云:唐永徽中,以阮常明為峰州都督,睹其土地千里,江山襟帶,於白鶴外建通聖觀,置三清像以為奇偉。別開前後二广/莫,擬塑護觀神像,未辨孰靈,焚香祝曰:此間神祇,苟能顯靈者,早現形狀,吾知塑樣。夜夢兩箇異人,面貌層稜,並擁徒屬,相呵相凌,趍常明爭居觀前。

常明問之:汝名字為誰?一稱土令,一稱石卿。常明曰:請試,孰藝勝者,前居。石卿跳躑一步到那邊江,忽然已見土令以那邊江住。石卿再跳一步復這邊江,已見土令先這邊住。於是土令得焉。即今敕封武輔忠翊威顯王是也。

自唐至今,千百餘載。其地傑神靈,祈禱報應,古今一也。

This is a very clear example of the use of Daoism to appropriate/subjugate local spirits. From this account, we see that a Tang Dynasty administrator, Ruan Changming, built a Daoist temple in Bạch Hạc, and that he summoned local spirits to appear so that they could serve as guardian, or protecting, spirits of the temple.

The description of these local spirits is negative. They are “uncivilized” in the way that they come in a group and are arguing with each other. They do not have a sense of a higher purpose.

However, Ruan Changming, the Tang Dynasty administrator, did have a sense of higher purpose. His goal was to get local spirits (and by extension, local people), to follow the way of imperially-accepted spirits, and that is what this record documents. The local spirits were given the task of “protecting” the Three Pure Ones (sanqing/tam thanh 三清), just as local people were supposed to “protect” the Tang Dynasty.

In appropriating/subjugating these spirits, Ruan Changming ultimately began to erase the original meaning of those spirits to local people. By creating statues of those spirits, he created an image of these deities that had never existed. His story about their willingness to serve as protecting spirits for Thông Thánh Temple was also new.

As time passed, however, this information became the only information that people knew about those spirits and that temple. Indigenous beliefs were thus erased, and a new culture was created in its place. It is that culture that we today refer to as “Vietnamese culture.”

This Post Has 5 Comments

Thanks for another blog.

It is interesting to see that Ruan Changming ( 阮常明), the Tang Dynasty administrator, shared the same last name of Nguyen which is about 40% population of current Vietnamese population. In China, Nguyen is not a common last name, I guess it is much less than 0.5%?

The Linh Nam chich quai has a reference under the entry for Mount Tan Vien to a spirit named Ruan/Nguyen, and the information supposedly comes from a book that another Tang administrator compiled around the same time as Zhao Chang:

“Seng Kun of the Tang’s Record of Jiao Region [Jiaozhou ji] records that the Great King of the mountain was the mountain sprite Mr. Nguyễn/Ruan, and that it was very potent and efficacious. During times of drought or flooding, when one beseeched [the spirit] for protection against calamity, it would respond right away. People never stopped to faithfully and reverently make sacrifices. It was often the case that if there was something which resembled a pennant seen floating about in a mountain valley on a clear day, and the people in the area would say that the mountain spirit had appeared.”

So that’s 2 Ruans/Nguyens, but I agree, it’s not many, and I think the only famous Ruan in Chinese history was Ruan Ji (maybe there was one more famous Ruan?):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruan_Ji

So where did all of the Nguyens come from? Did these two Tang-era Ruans have anything to do with the eventual popularity of that surname? I have no idea, but thanks for pointing this out!! 🙂

I’ve heard ( undocumented ) that when a new dynasty takes over , the subjects are induced , coaxed more or less willingly to take the name of the new ruler , to show their allegiance , their loyalty .

In VN the Nguyên were the latest dynasty ; that’swhy the name is so prevalent

In some late-Ming and Qing-era texts there is information about the mythical figure “Ly Ong Trong” but he is referred to as “Nguyen Ong Trong.” I don’t know how that information got there because he is Ly Ong Trong in the An Nam chi luoc and the Annan zhiyuan, 2 texts that Chinese writers potentially had access too.

In any case, I think I read somewhere that after the Ly Dynasty came to power, people who had the surname Ly had to change it to Nguyen.

There are cases in Chinese history where minority peoples on the periphery were allowed to use the imperial surname if they submitted. So during the Song some Tai-speaking peoples got the surname “Zhao.” the surname of the Song Dynasty ruling family.

The surname of the Tang ruling family was Ly/Li, so perhaps something similar happened in Vietnam at that time. If that happened, and if those people all had to change their names later to Nguyen, then that would explain why there started to be a lot of Nguyens in the region.

Just a guess.