In 1976, linguists Jerry Norman and Tsu-Lin Mei published an influential article entitled “The Austroasiatics in Ancient South China: Some Lexical Evidence.” In this article, Norman and Mei offered linguistic evidence that they said could “show that the Austroasiatics inhabited the shores of the Middle Yangtze and parts of the southeast coast during the first millennium B.C.”

One example they look at is a word meaning “to die.” Norman and Mei state that “In Zheng Xuan’s commentary on the Zhouli, the gloss 越人謂死為札 “The Yue people call ‘to die’ 札 occurs.”

Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 was a famous commentator who lived in the second century CE.

Pronounced today as “zha,” Norman and Mei discuss how it may have been pronounced in Zheng Xuan’s time and argue that it is an Austroasiatic term and that it is the same word as the current word for “to die” in Vietnamese, “chết.”

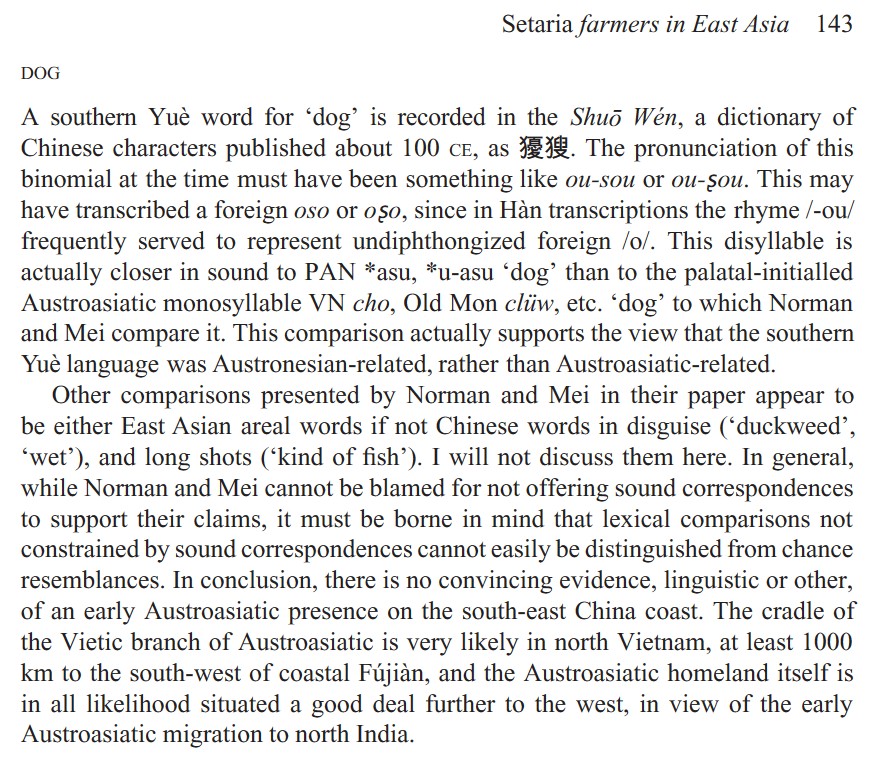

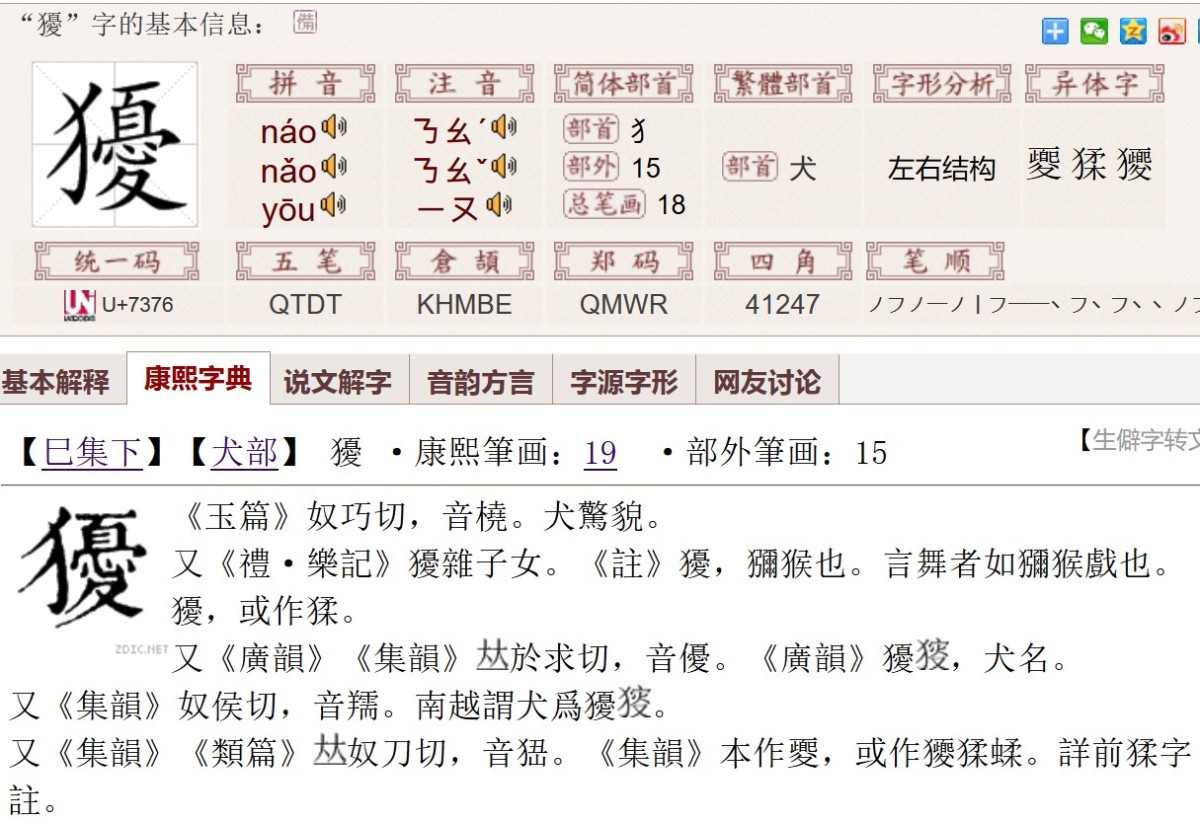

Another example Norman and Mei point to is a word meaning “dog.” In a dictionary from the early second century CE, the Shuowen 説文, a section on characters that contain the dog radical (犬) has a gloss on the term “sou 獀” that says “‘sou’ – Southern Yue [people] call dogs ‘naosou’” 獀,南越名犬獿獀也。

Norman and Mei argue that this word, which is today pronounced naosou, would have been pronounced at the time the Shuowen was compiled as something like “nog-siog.” They say that “The first character of the compound probably represents a pre-syllable of some kind,” and that “at the time of the Shuowen (121 A.D.), -g had probably already disappeared.”

Based on these assumptions, Norman and Mei argued that this was an Austroasiatic term and was the equivalent of words for dog like “chó” in Vietnamese and “shɔ” in Palaung.

In 2008, linguist Laurent Sagart called into questions these claims in a book chapter entitled “The Expansion of Setaria Farmers in East Asia: A Linguistic and Archaeological Model.”

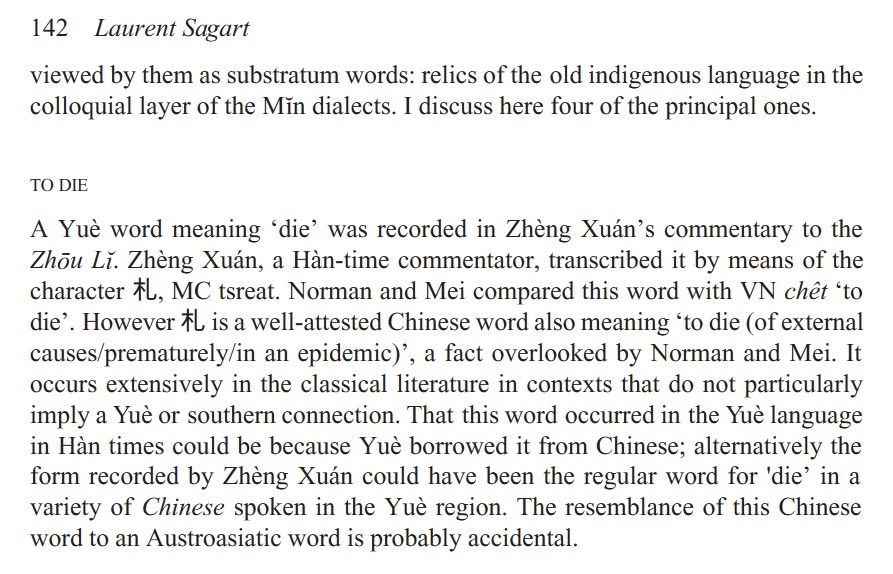

With regards to Norman and Mei’s claim that the term zha 札, meaning “to die,” was of Austroasiatic origin, Sagart stated that “札 is a well-attested Chinese word also meaning ‘to die (of external causes/prematurely/in an epidemic),’ a fact overlooked by Norman and Mei. It occurs extensively in the classical literature in contexts that do not particularly imply a Yue or southern connection.

“That this word occurred in the Yue language in Han times could be because Yue borrowed it from Chinese; alternatively the form recorded by Zheng Xuan could have been the regular word for ‘die’ in a variety of Chinese spoken in the Yue region. The resemblance of this Chinese word to an Austroasiatic word is probably accidental.” (142)

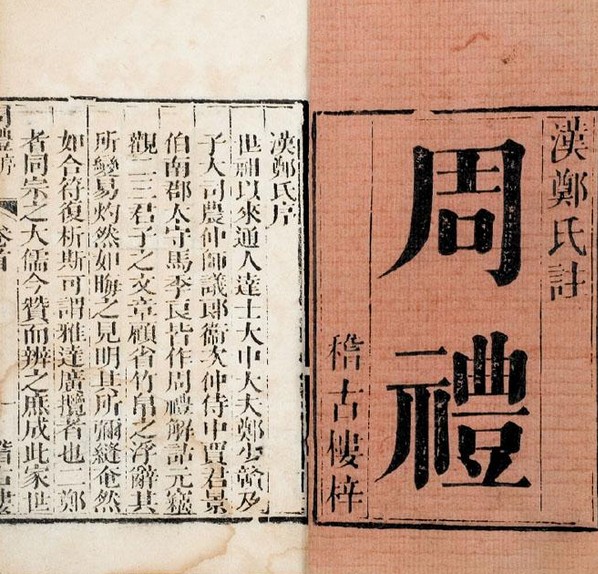

I’m not certain that this term “occurs extensively in the classical literature,” however it does appear a few times in compounds (zhaxiong 凶札, zhasang 札喪) in the work in which Zheng Xuan’s gloss appears, that is, the third-century BCE Rites of Zhou (Zhouli 周禮).

The compound that Zheng Xuan glosses there is xiongzha 凶札. This is what he says:

“‘Xiong’ means famine from a year of bad crops; ‘zha’ means death from an epidemic. Yue people call ‘death’ [or ‘to die’] ‘zha.’”

凶,謂凶年飢荒也﹔札,謂疾疫死亡也。越人謂死為札。

Jia Gongyan, a Tang dynasty scholar who added a second level of commentaries to the Rites of Zhou, glossed the term zhasang 札喪 as follows:

“Jia Gongyan explained: ‘zha’ means epidemic illness; ‘sang’ means to die.”

賈公彥 疏:“札謂疫病,喪謂死喪。

Viewed from this larger textual context the fact that from at least the third century BCE to the Tang there was knowledge about this term, Zheng Xuan’s added comment, after his gloss, about Yue people seems to fit Sagart’s conclusions that any similarity between that term and another in a Yue language was coincidental.

Sagart has also challenged Norman and Mei’s claim that naosou (“nog-siog”), a term that the Shuowen says is the word for dog in Nanyue, or Southern Yue, is an Austroasiatic term. To quote:

“The pronunciation of this binomial at the time must have been something like ou–sou or ou–şou. This may have transcribed a foreign oso or oso, since in Han transcriptions the rhyme /-ou/ frequently served to represent undipthongized foreign /o/.

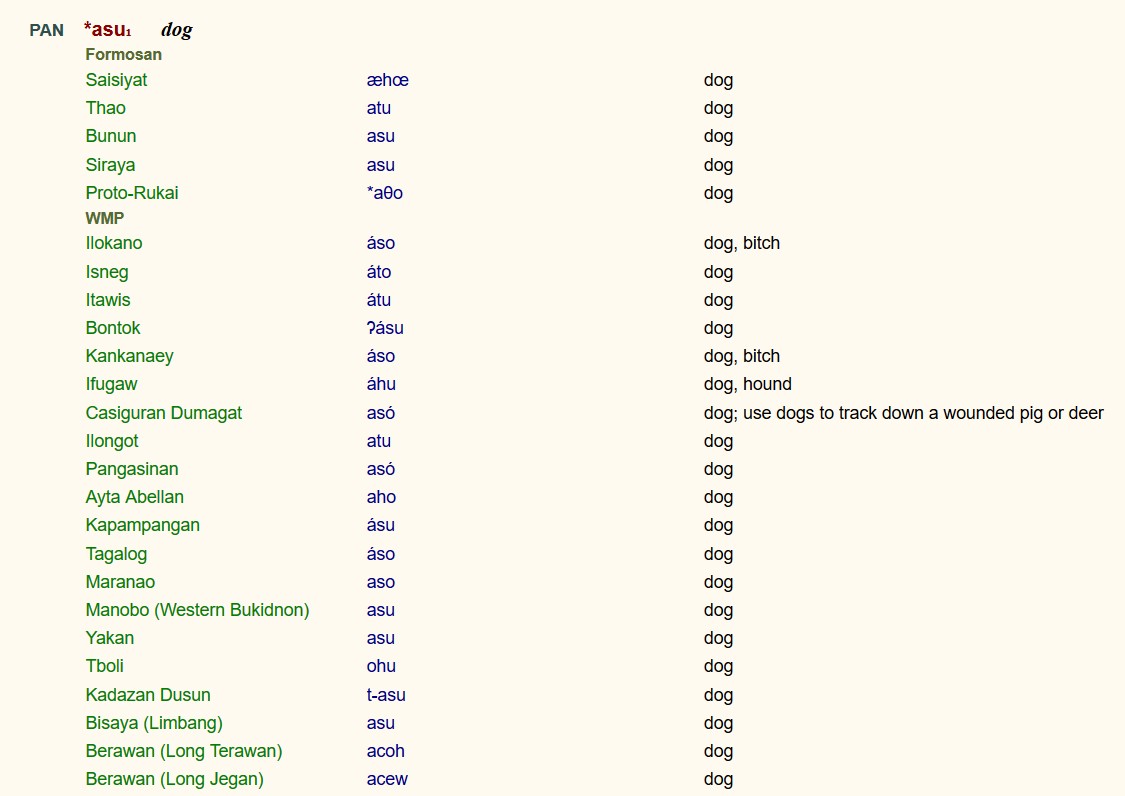

“This disyllable is actually closer in sound to PAN [i.e., proto Austronesian] *asu, *u-asu ‘dog’ than to the palatal-initialled Austroasiatic monosyllable VN cho, old Mon clüw, etc. ‘dog’ to which Norman and Mei compare it.

“This comparison actually supports the view that the southern Yue language was Austronesian-related, rather than Austroasiatic-related.” (143)

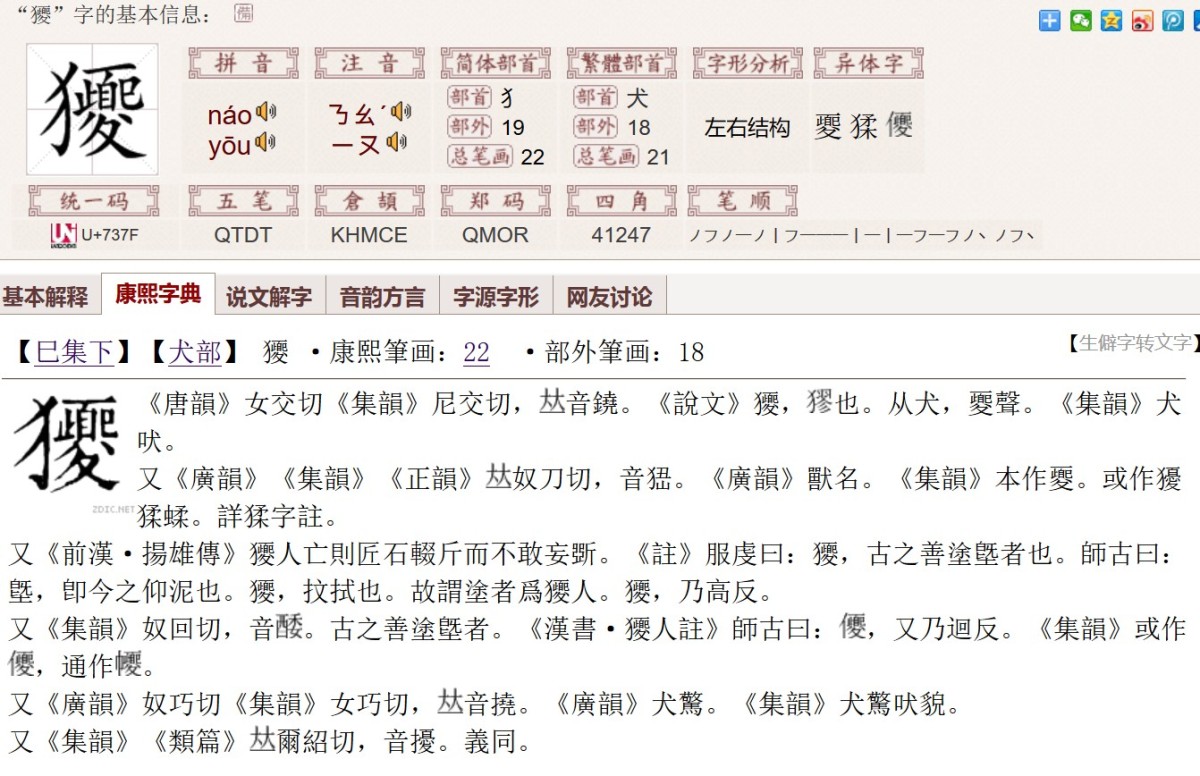

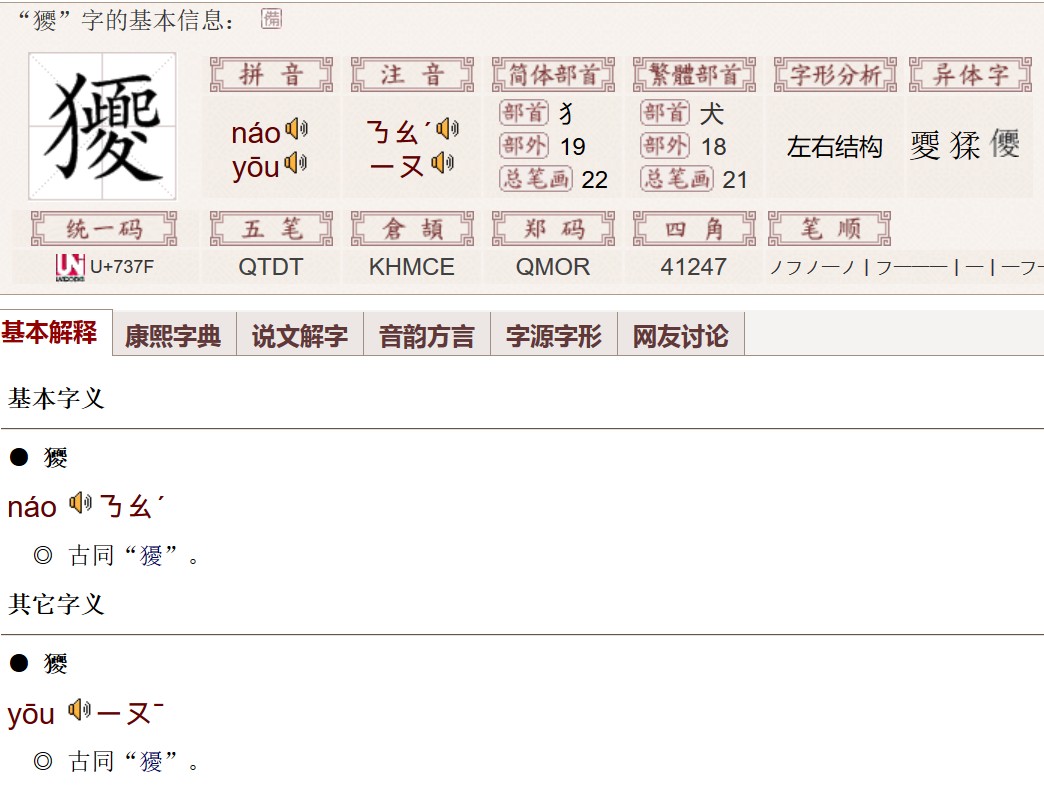

How does Sagart know that this term was pronounced as something like “ou–sou” rather than “nao–sou” as Norman and Mei claimed? That is, why does he think the first character (獿) was pronounced as “ou” rather than “nao”? He doesn’t explain, but there is an explanation.

The early-second-century text where this term appears, the Shuowen, does not indicate how this term was pronounced. For that we have to look at rhyming dictionaries, and there are dictionaries from later periods that do this.

One, the Guangyun 廣韻 (Extended Rhymes), is from the Northern Song period (960-1126), and the other, the Jiyun集韻 Collected Rimes), was produced in 1037 during the Southern Song period.

Both of the above rhyming dictionaries, and earlier ones, indicate that the character 獿 can be pronounced “nao.” And this is the information that Norman and Mei undoubtedly based their examination on.

However, this character is an ancient variant for another character – 獶, and when we look for how that character was pronounced, we find a different pronunciation.

In particular, the Guangyun states that獶 is pronounced like “you” (於求切,音優), and as an example of this, the text indicates the very same term for “dog” that appeared in the Shuowen, which would mean that it should be pronounced something like “you–sou.”

I do not know how the compilers of that dictionary determined that, but this is the earliest example that we have (unless someone can find something earlier) of how Chinese scholars believed that term should be pronounced.

I must note that the subsequent dictionary, the Jiyun, then stated that this term is pronounced “nou,” and also cited the dog term in the Shuowen as an example of the usage for this pronunciation.

Once again, I do not know how the compilers of that dictionary determined that either. However, in looking up the term for dog in this Austronesian Comparative Dictionary, one can see why Sagart would suggest that this term comes from an Austronesian language, as “you-sou” or “ou-sou,” the earliest recorded pronunciation, is very close to the word for “dog” in many Austronesian languages.

Norman and Mei’s article has been very influential. However, in reading it today, I’m struck at how meagre the evidence is and how forced their explanations seem. To get “nog-siok” to become “chó,” for instance, Norman and Mei have to account for various linguistic changes that must have taken place.

To go from “you-sou” or “ou-sou” to “aso” or “asu,” on the other hand, strikes me as pretty straightforward.

Putting the linguistic arguments aside, however, (as I’m not a linguist) I would argue that one reason why this article has been so influential is because many scholars have “wanted” to believe it.

For people who work on Southeast Asia, the idea that “Southeast Asia” extended into “China” in the past makes them feel good.

Similarly, given that the closest existing Austroasiatic-speaking society to southern China today is Vietnam, for people who work on Vietnam the idea that “ancestors of the Vietnamese” or “people related to the Vietnamese” were also present in areas further to the north in the past makes them feel good too.

Finally, for scholars who work on China, the presence of “Southeast Asian” peoples in “China” enables them to deconstruct the idea of a homogenous and eternal “Chinese people,” and that makes them feel good as well.

The evidence that Norman and Mei offered, however, is problematic (although it seemed bold in 1976). And now it has been seriously challenged by Sagart.

At the same time though, evidence for a significant Austronesian (or pre- or proto-Austronesian) presence in the area south of the Yangzi in the past is growing.

So scholars who want to deconstruct China are still in business, and people in island Southeast Asia can now start getting excited. But for those who work on Austroasiatic societies. . . I know it hurts, but it’s time to move beyond Norman and Mei.

This Post Has 18 Comments

If we separate ethnicity from language then these problems can be seen through more objective lens. Chinese is Sino-Tibetan language but genetics of Chinese is not the same as Tibetan or Burmese or combining both. Thai population is very heterologous but they speak only Thai as official language. Similarly, Vietnamese have a diverse ethnic backgrounds but a form of Vietic language becomes the official language.

Based on what I read, a language usually become official language if the elites speak it. Based on some recent arguments about the hometowns of Ngo Quyen and Phung Hung, and the facts that many Red Delta River families were actually recent immigrants from Ai Chau, I guess it can be reasonably concluded that Vietic language was imposed on some populations in Vietnam by the imperial courts and movement of elites from 8th century.

Regarding the origin of Vietnamese, I feel that it is usually oversimplified by two opposing camps. Those anti-Chinese claims that Viets have always been Viets (meaning the major population is of native origin) and those pro-Chinese claims that Viets are Chinese immigrants from various times in the past. Personally I think the fact lies somewhere in between. This is not to mention the Southward expansion during the second millenium, which must have included more Mon-Khmer blood from the Cham and Cambodian into present day Vietnamese.

My family for example, is Viet on both sides, with recorded Chinese ancestry on my mom’s side (recent migration from Guangdong) and recorded Vietnamese ancestry on my dad’s. But aside from her chinese family name, my maternal cousins look Southern Chinese or Vietnamese while some people on my dad’s side have heavy Mongolian or East asian look (single eyelid eyes and straight narrow and high nose).

Vietic language was not imposed ; rather it sprang up spontaneously thru the ethnic melting .By the way , Vietnamese words are 2/3 from ” chinese ” origins so it’s rather a sinitic language . Likewise with England and Latin America or French Antilles , foreigners came to conquer and rule over the aborigenes ; in Latin America and French possessions , sprang up creole languages . Unlike Great Britain , the ruling class did not set themselves apart from the natives ( in England , the aristocracy invisibly segregated itself from the people , like Indian brahmins from outcasts )

2/3 words in Korean and Japanese have Chinese origin but Korean and Japanese still belong to Altai. Judge the language is not only based on vocabulary. The standard is about basic words as well as grammar.

I agree with the hypothesis of northwards of proto-Vietic but I want to inform that Phung Hung maybe not Vietic-speaking people. His title is Bố Cái Đại Vương. Bố is from pố – a Tai words and a lot of others – you can read from this blog actually are Tai.

Tai-speaking people live in Thanh Hoa, Nghe An region was really early. According to Chinese record, it happened before 40 CE.

It means that not all of southern people are proto-Vietic. This make everything more complex.

As for Ngô Quyền, I read some hypothesis very make sense that he actually was not from Duong Lam.

@Nguyen Bac Wasn’t the theory that Japanese and Korean language being both Altaic(or even related) were already dismissed ?

@Nguyen Bac: you probably meant that the currently designated Duong Lam village is not the real birthplace of Ngo Quyen. That has been attested in some recent articles.

No I did not mean that there was no Autro-asiatic people in the Red River Delta. What I meant is that the dominant culture (the DongSon) of Red River Delta in the beginning of the first millenium is probably Tai, since bronze drum culture stretched from Red River Delta to GuangXi and Yunnan. It is difficult not to deduce that this cultural phenomenon is a common feature of a single united ethnicity.

@diemhentamhon: No, I mean Ngo Quyen maybe not from Duong Lam, he maybe from Cat Loi.

Sách Thuyền uyển tập anh (một cuốn sách về lịch sử phật giáo Việt Nam) chép: “Đại sư Khuông Việt {Trước tên là Chân Lưu} (933 – 1011). Chùa Phật đà, làng Cát lợi, Thường lạc. Người Cát lợi, họ Ngô, thuộc dòng dõi Ngô Thuận Đế.

The book dated from Tran dynasty, noted that Khuong Viet monk has Cat Loi as hometown. This can lead to Ngo Quyen is from Cat Loi.

Khuong Viet is Ngo Chan Luu, son of Ngo Xuong Ngap, and grandson of Ngo Quyen.

All other source date latter consider to Thuyen uyen tap anh.

About Dongson culture, the site where found biggest archaeological thing is actually on the south of Red River Delta where Muong people is dominant.

Actually dog in Vietnamese is not cho but rather con chó. chó in Vietnamese is derived from jor in Khmer. 札 bears no resemblance to chết. written in chữ Nôm as 折(used as the phonetic)[,one of many Chinese words meaning “to die”] over 死 (another word meaning “to die” in Chinese).

So the word for “dog” in Khmer is chkae ឆ្កែ.

The “jor” you are referring to is a term that is used in the calendar when referring to ‘Year of the Dog’ ឆ្នាំចរ. That word for dog in Khmer actually comes from Vietnamese (and is sometimes written as ច cɑɑ): the Year of the Dog, the 11th year of the lunar calendar. Vietnamese chó ឆ្នាំច

Search for “dog” in the “text” box of this dictionary: http://sealang.net/khmer/dictionary.htm

As for why “dog” is different in Khmer and how is it that the Vietnamese word for “dog” was adopted into Khmer through a calendar. . . I need someone who knows about this to explain it to me, as I’m not sure.

How about one, two, three, four and five in Vietnamese and Cambodian languages? it seems that the pronunciations of one to five in Vietnamese are somewhat similar to that of Cambodian:

English Vietnamese Cambodian

One Mot Muəj

Two Hai Piː (pɨl)

Three Ba Bəj

Four Bon Buən

Five Nam Pram

Were the five numbers (1 to 5) in Vietnamese derived from that of Cambodian or vice versa?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khmer_numerals

A southern Yuè word for ‘dog’ is recorded in the Shuō Wén, a dictionary

Chinese characters published about 100 ce, as 獶獀. The pronunciation of

binomial at the time must have been something like ou-sou or ou-ʂou. This

have transcribed a foreign oso or oʂo, since in Hàn transcriptions the rhyme

frequently served to represent undiphthongized foreign /o/. This disyllable

actually closer in sound to PAN *asu, *u-asu ‘dog’ than to the palatal-initialled

Austroasiatic monosyllable VN cho, Old Mon clüw, etc. ‘dog’ to which Norman

and Mei compare it. This comparison actually supports the view that the southern

Yuè language was Austronesian-related, rather than Austroasiatic-related.

(Sagart )

I agree with hìm

A Chinese Vocabulary of Cham Words and Phrases

E. D. Edwards and C. O. Blagden

Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London

Vol. 10, No. 1 (1939), pp. 53-91

Page 66 :

201 犬 dog 阿 搜 .

Under the 1000-year of ” chinese ” appartenance or domination , there were some numbers of uprisings . Were they documented ? and were they initiated by ” natives ” or Han separatists ?

What were Ngô Quyền’s origins ? Was he an assimilated native wearing Han name or a Han colonist ?

Lý Bí hoặc Lý Bôn ruled independantly (503-548 ) from a southern “chinese ” kingdom called Liang during the Nan-Pei chao period , he is supposed to come from a BaiYue family .

Contrariwise , the Tran dynasty who repulsed the Mongols is known to originate from Fou-kien

Lí Bôn is a Han Chinese whose family fled to Vietnam during WangMang. Somehow Vietnamese historians made him a Baiyue descendant to make them feel good. There was no mentioning of Lí Bôn’s Baiyueness in the Chinese sources. Considering Tao Kan, a Wu Yue Chinese was looked down upon by contemporary Northerners, it can be assumed that Han people during Han dynasty only refer to Central Plain Han, not Han from Jiangnan like during Song and Ming.

Yes, but riroriro brings up a good point. The people seeking some form of autonomy from (Chinese) dynastic rule in this region (including the Guangdong area) in the centuries after the Trung Sisters’ rebellion were all part of that larger “Chinese” world.

Back to the issue of Han and non-Han though, there is another interesting term that appears in Chinese sources (certainly during the Tang) and that is “Giao/Jiao person” (Giao nhân/Jiaoren 交人). An example might be, for instance, that “A Giao person passed the civil service exam.”

In such an example (and I have seen examples like that one), it is clear that such a person was literate in classical Chinese, but what made him a “Giao person”? Was it simply that he was from Giao Châu/Jiaozhou? In which case, this could refer to a Han person who lived in the far off land of Giao/Jiao. Or did it mean that this person was ethnically different from Han people? If that was the case, how was such a person different? Was he completely different? In which case we could think of such a person as a Sinicized indigenous person. Or was he of mixed-blood? In which case, “Giao person” would refer to what the French referred to as a Mếtis.

I have not been able to determine what exactly that term meant to the people who used it.

Laurent Sagart first dismisses the presence of Austro-Asiatics along the southeastern coast of China, then he proposes that most of the Austronesian ancestors of Tai-Kadai’s language was replaced by an Austro-Asiatic related language upon arriving back to the mainland. It sounds rather contradictory.

@Igo-I: I think Sagart point is Austro-Asiatics was not living along the coast. They live around Quangxi region and the south of it before replacing by Tai-speaking people.

This hypothesis first introduced by Peter Bellwood.

You mean this paper http://faculty.washington.edu/plape/pacificarchaut12/Bellwood%202004.pdf ?

The proposal about the coastal location where the Austronesian Ancestor of Tai‑Kadai arrived in during their out-of-Taiwan migration period is only tentative because Tai substratum can be found in Wu dialects and Tai words have been discovered in the Chǔ bronze inscriptions.

@Nguyen Bac Wasn’t tbe theory that Japanese and Korean language being both Altaic(or even related) were already dismissed ?