In his 1978 book, Orientalism, Edward Said documented how Western scholars and writers, particularly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, produced knowledge about “the Orient” which, taken together (as a discourse), created a negative picture of that part of the world. Said argued further that this “knowledge” was also used to justify Western imperialism as an effort to “help” or “uplift” the East.

A key element of this body of Orientalist knowledge was the idea that the East and the West constituted a pair of opposites. In the nineteenth century, one of the most common ways of expressing the differences between this pair of opposites was to say that the East/Orient was “static” and the West/Occident was “dynamic.”

As for what explained this difference, multiple reasons were suggested (from politics to race), but what all of the explanations shared was the idea that “the East” and “the West” both had essential characteristics.

Although it was Westerners who came up with this idea of a static East and a dynamic West, in the early twentieth century Chinese reformers adopted these same essentialized categories as they debated over how to transform Chinese society.

The failure of the 1911 Revolution to create a stable republic led reformers to look more closely at Chinese society and to question why it was unable to transform.

At the same time, the horrific violence of World War I led to a sense, both in China and in Europe, that the West did not have all of the answers.

As such, Chinese intellectuals in the 1910s and 1920s put forth differing ideas as for which direction Chinese society should go (some felt it needed to Westernize, others felt it needed to blend East and West, etc.), but in their arguments they repeatedly made reference to this idea that the East was static and the West was dynamic.

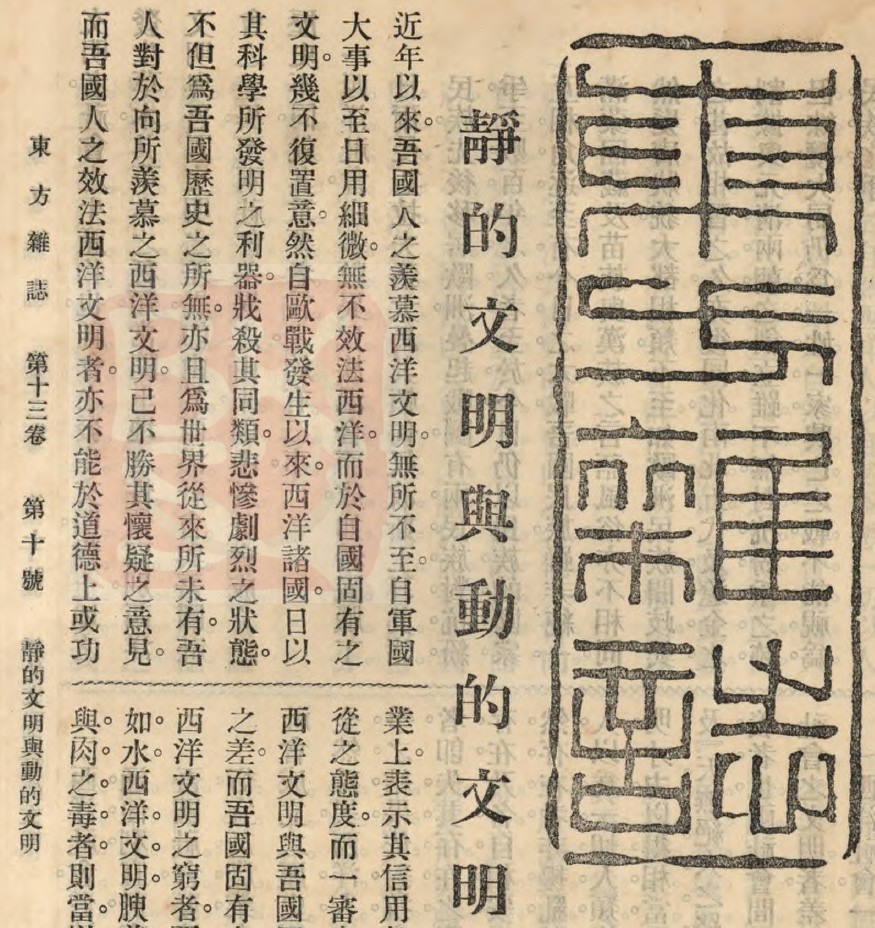

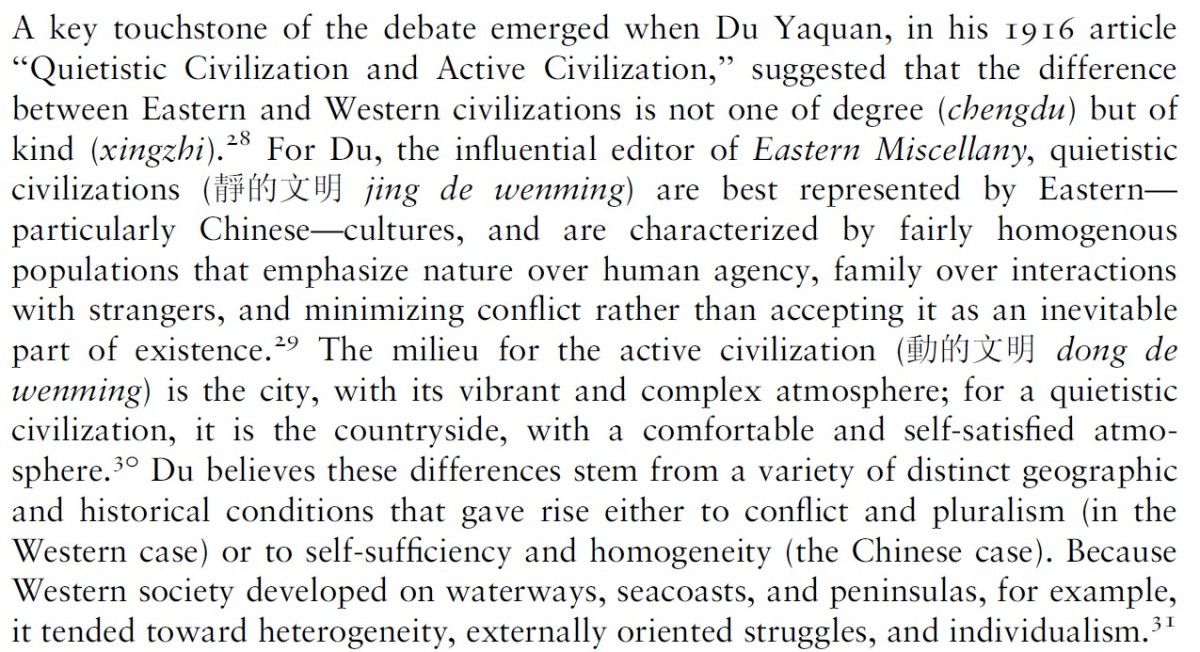

Here is a summary of how Du Yaquan 杜亜泉, the editor of an influential journal called the Eastern Miscellany (東方雜誌), described the differences between the supposed static East and the dynamic West in an article that he published in 1916 entitled “Static Civilizations and Dynamic Civilizations” (靜的文明與動的文明):

“[Static] civilizations (靜的文明 jing de wenming) are best represented by Eastern – particularly Chinese – cultures, and are characterized by fairly homogenous populations that emphasize nature over human agency, family over interactions with strangers, and minimizing conflict rather than accepting it as an inevitable part of existence.

“The milieu for the [dynamic] civilization (動的文明 dong de wenming) is the city, with its vibrant and complex atmosphere; for the [static] civilization, it is the countryside, with a comfortable and self-satisfied atmosphere.

“Du [Yaquan] believes these differences stem from a variety of distinct geographic and historical conditions that gave rise either to conflict and pluralism (in the Western case) or to self-sufficiency and homogeneity (the Chinese case).

“Because Western society developed on waterways, seacoasts, and peninsulas, for example, it tended toward heterogeneity, externally oriented struggles, and individualism.”

[Leigh Jenco, “Culture as History: Envisioning Change Across and Beyond ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ Civilizations in the May Fourth Era,” Twentieth Century China vol. 38, no. 1 (2013): 41.]

From Du Yaquan’s adoption of Western Orientalist ideas in the early twentieth century, let us now move to the final decade of the twentieth century and look at Trần Ngọc Thêm’s Searching for the True Nature of Vietnamese Culture (Tìm về bản sắc văn hóa Việt Nam).

We saw in the previous post that Trần Ngọc Thêm used these exact same terms, “static” (tĩnh = jing 靜) and “dynamic” (động = dong 動), in reference to two main cultural patterns that he argues emerged in antiquity and continued to influence peoples lives over the centuries even after their societies transformed.

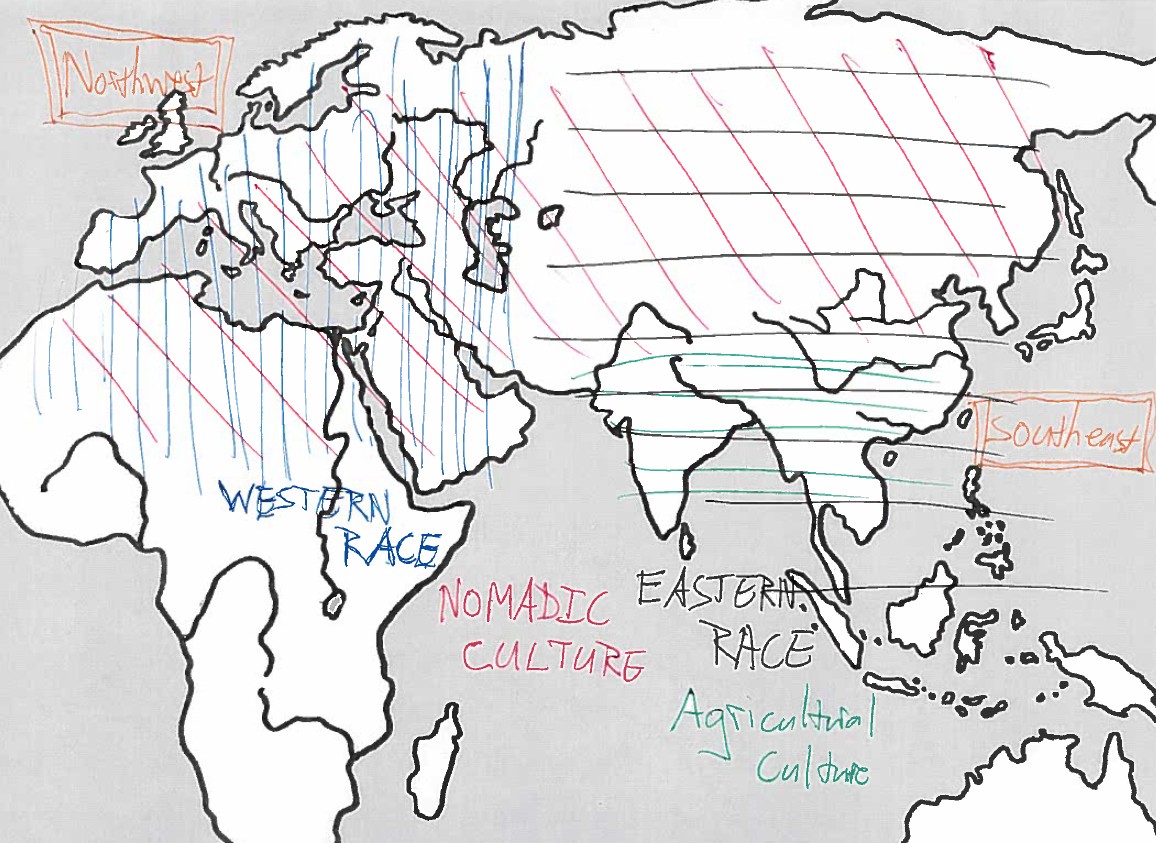

In particular, Trần Ngọc Thêm argues that the area extending from northern Africa across Europe and eastward through Siberia, which he calls the “Northwest,” is a region which was inhabited from a very early time by nomads who valued the dynamic (trọng động), whereas the area extending from somewhere around the Yangzi river and Japan southward into mainland Southeast Asia, or what he calls the “Southeast,” is a region that was inhabited from a very early time by agriculturalists who valued the static (trọng tĩnh).

Here is how Trần Ngọc Thêm describes the differences between these two groups.

Agriculturalists depend on nature (phụ thuộc nhiều vào thiên nhiên). They stay in a set place (ở cố định một chỗ) with their house and their crops, and therefore they have a sense of respect (có ý thức tôn trọng) for their surroundings and do not dare to compete with nature (không dám ganh đua với thiên nhiên).

Living in harmony with nature, according to Trần Ngọc Thêm is the desire of the static-valuing agriculturalists of the East.

As for nomads, if they don’t feel that one place is convenient then they will easily leave it and go to another. As such, on a psychological level they look down on nature (coi thường thiên nhiên).

Therefore, according to Trần Ngọc Thêm the dynamic cultures of the West always possess the wish to conquer and control nature (chinh phục và chế ngự thiên nhiên).

What is clear from this description is that Trần Ngọc Thêm portrays agriculturalists in a more positive light, but he says that there are good and bad points about both.

He says, for instance, that while respecting nature and living at ease is good, this also makes people become timid and hesitant (rụt rè, e ngại). And while looking down on nature is bad, this attitude nonetheless encourages people to bravely face nature (dũng cảm đối mặt với thiên nhiên) and it encourages science to develop (khuyến khích khoa học phất triển), but then again it also leads to the destruction of the environment (nhưng có cái dở là hủy hoại môi trường).

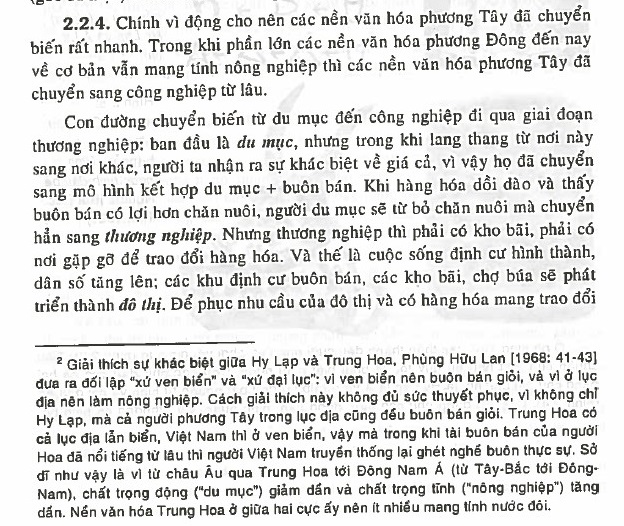

According to Trần Ngọc Thêm, yet another distinction between the dynamic-valuing nomads and the static-valuing agriculturalists is that the dynamism of nomadic culture led to societal changes.

He notes, for instance, that societies in the West changed from being nomadic to engaging in trade to establishing industries.

More specifically, Trần Ngọc Thêm argues that as Western nomads wandered around they noticed that things had different values in different places. This gave them the idea to combine commerce with their nomadic lifestyle. As they got better at commerce, they had more goods, and that required settling down in a place where they could have a warehouse, and that ultimately created cities, and from those cities industry eventually emerged.

What should be clear here is that this Northwest/Southeast, nomad/agriculturalist, dynamic/static binary that Trần Ngọc Thêm discusses is essentially the same binary that Chinese intellectuals like Du Yaquan discussed in the early twentieth century.

That binary was in turn based on an Orientalist/essentialist/racist view of the world which saw the West in positive terms as dynamic, and the East in negative terms as static.

Du Yaquan believed in this depiction of the world and wished to improve China’s position by blending some of the elements of Eastern and Western culture.

Trần Ngọc Thêm likewise believes in this binary, but he also inverts it, as he ultimately portrays the East as superior in many ways to the West.

Sure, perhaps the people in the East are “timid” and “hesitant,” and economically it might not have always been as prosperous as the West, but certainly the “respect for nature” of the agriculturalists in the East is more admirable than the “destruction of the environment” which the “dynamism” of the “nomad-origin culture” is responsible for creating.

This is all incredibly problematic.

Inverting an essentialist/racist concept does not change concept from continuing to be essentialist/racist. So in other words, by using the concepts of “static” and “dynamic” to describe entire cultures, Trần Ngọc Thêm is employing nineteenth-century Orientalist/essentialist/racist ideas to educate people in the twenty first century.

The use of binary categories like these to describe entire societies was discredited in Anglo-European academia decades ago and is yet again another sign of how weak and out-of-touch with the world the scholarship in this book is.

However, to get back to the discussion of the ways in which Trần Ngọc Thêm’s ideas differ from those of people like Du Yaquan in the early twentieth century is that even though Trần Ngọc Thêm employs the same nineteenth-century Orientalist binary categories in his discussion as Du Yaquan did, whereas Du Yaquan saw China as the prime example of a static Eastern culture, it is clear that Trần Ngọc Thêm sees areas further to the south as the best example of the true static Eastern culture.

We can get a sense of this from a comment that Trần Ngọc Thêm makes about a theory that Chinese scholar Feng Youlan once came up with. Feng Youlan, echoing a point that Du Yaquan made above, once argued that the contrast between the West and the East can be seen as a contrast between maritime-oriented and continental-oriented societies (yes, that’s right, another essentialist binary category).

According to Feng Youlan, Western countries were maritime-oriented and this led to an emphasis on trade, whereas China had historically been continental-oriented.

Trần Ngọc Thêm, however, disagrees with this by stating that Vietnam has a long coastline but has historically not been good at trade, whereas China has both land and coasts and has a long history of trading.

The reason for this, according to Trần Ngọc Thêm, is that there is not an exact divide between the Northwest culture of valuing the dynamic and the Southeast culture of valuing the static. Instead, these values are spread across a spectrum that gradually changes from the dynamic to the static somewhere in the middle of China. . . so at least some people in China are “dynamic.”

If we were to map all of these ideas out, the map might look something like the map above.

While, according to Trần Ngọc Thêm (as we saw in the first post), the world is divided into two main races (a Western and an Eastern one), he argues that it is also divided between peoples who are influenced by the ancient cultures of agriculturalists (who are static) and nomads (who are dynamic).

As we started to see above, people who are static agriculturalists are presented in a positive light in Trần Ngọc Thêm’s book. We will see this even more clearly later.

And if you look at the map, the place where the true static agriculturalists live is centered right around the area where. . . the Việt live.

This is how the argument for Việt supremacy is created. You take nineteenth-century Orientalist/essentialist/racist ideas and invert them to make a certain population look good, and then. . . you declare that this is all reflected in the Yijing.

That is the topic that we will turn to next.

This Post Has 11 Comments

If Trần Ngọc Thêm argument about east-west, static-dynamic, agriculturalists-nomads were to be represented in the above map the where is our America continent stand? Are you dynamic because you are in Hawaii and I am static for I am land-locked in the middle of the continent? Back into the past, just a few hundred years who are the residents of dynamic Hawaii and static Canada-America. I just wonder. Vietnamese are away the best…what a warped concept!

Exactly!!! Very good points.

It gets even crazier (I think) when you think about Trần Ngọc Thêm’s “Southeast.” Shouldn’t that be the world of the Cham, Malays, Dayaks, Javanese, Balinese, and the inhabitants of all of the other islands in island Southeast Asia?

Nooooooo!!!! The “Southeast” is the world of the Việt. Yes, at times he mentions some of the ethnic groups in the Central Highlands, but only briefly.

This is very much a Việt-centric view of the world.

What did/do you expect? Do you expect instead the Vietnamese to automatically accept the Eurocentric version of the world map in which “the West” is the defender of civilization, distributor of democracy, inheritor of glorious ancient Greece and Rome who are inventors/models of everything good in the world? Or the Sinic one in which the PRC now is the descendant of the ancient Zhou, Han, Tang, Song the Middle Kingdom, the highest culture on earth after which all 夷狄蠻胡 should follow?

Yes, it’s twenty first century (counting from the birth of Jesus), the age of globalization and textbooks, mass media and everything in America, Europe refer to themselve as the West, Occident in contrast to the East, Orient. Though you can see that Asia is in the west of America and EU if you just turn the globe a bit from the usual “centre” (go for a search with “world map” in google if you forget how it is portrayed)

Tran Ngoc Them or Hu Shi or any other man each has his/her own view of the world and they also have their own ways to express them using/employing differrent concepts, methods. It does not matter where and when the tools come from but how they are used. To the general Vietnamese and Chinese, they make sense. Yes that is how they make sense of their world. I would not expect them to do it my way or any way other (my supposed ideal objective way).

If you find it crazy about Them’s Southeast then you should go mad (insane) about “the West” too.

It’s also ironic to try to expose “racism” in Vietnam’s scholarship. The scholars aim at their audience, Tran Ngoc Them tried to give an explanation and he did a good job for his audience. His works are clear and make sense to the general Vietnamese. He did not aim at and has no responsible to make it make sense to other audience.

Though I do not agree with Tran Ngoc Them but I understand what he tried to say and I do not judge his moral ground.

Thanks for your comment.

First of all, “racist” isn’t the most accurate term to use, but I can’t find another that is more accurate. I used it in the title, but I used other terms in the text. TNT’s writings combine racialization/essentialization/Orientalism, etc. That said, the end result of what he writes places the Viet at a higher place than other peoples, and it does so by using the above techniques (racialization/essentialization/Orientalism). In a general sense, I would call that “racist,” but it is really a mix of racialization/essentialization/Orientalism/environmental determinism.

I’m not sure why you think that the alternative to what TNT wrote can only be EITHER Euro-centric OR Sinic. Why can’t it just be “good scholarship” that is based on ideas and scholarship that anyone can accept?

To explain this, let’s look at some changes that have taken place in the basic university curriculum in the US. If we could go back to 1950 we would find that virtually every university in the US had basic courses on “Western Civilization” which essentially taught people to, as you say, “accept the Eurocentric version of the world map in which “the West” is the defender of civilization, distributor of democracy, inheritor of glorious ancient Greece and Rome who are inventors/models of everything good in the world?”

By contrast, today virtually every university in the US (down to the smallest community colleges) has replaced “Western Civilization” with “World History.” What is more, if you look at the textbooks that are used, and the way that courses are organized, it’s clear that they are not “Euro-centric” or “Sinic” or anything like that. They attempt to look at the history of the world as rationally as possible, and point out how the world we live in changed over time.

Why did this change take place? Well there were many changes that took place in the world of scholarship in Europe/North America/Australia in the 1960s-1980s. In the process, some of the concepts that “Western Civilization” courses were based on – Euro-centric ideas, racialized logic, essentialized categories, Orientalist views of the world, etc, – changed dramatically.

Again, why did this happen? Partly it was just the result of people “getting smarter” and realizing that older ideas were flawed, but it was also the result of many social changes at that time (including opposition to the Vietnam War) that made people realize that “the audience” was actually bigger than they had been addressing.

Think about it this way: If you were Asian-American or African-American or a woman and you were taught about how great Socrates was, and that’s it. . . you’d probably stop and wonder: Is that really all there was? And the answer is that of course there was more to the past than that, and this is something else that has led scholarship to change.

This has not led to “Euro-centric” writings or “Sinic” writings. It has led to scholarship that can be read by anyone and make sense.

With that in mind, think about TNT’s textbook. Who does it make sense to? It is not going to make sense to anyone who is trained in Europe/North America/Australia today because it is based on concepts that have long been proven in those places to be inaccurate (which is why Vietnamese students who go to those places have to “unlearn” a lot of what they learn in Vietnam). I think that it will also not make sense to certain peoples within the borders of Vietnam as it is definitely Viet-centric.

So what’s wrong with doing what people in the US have attempted to do with World History? Why not just write for a “human” audience, rather than an “ethnic” audience. After all, many of the members of that ethnic group will interact/study/work with other humans. Don’t we want them to be as perceptive as their fellow human beings around the globe?

I don’t think that there are only 2 alternatives and I did not say it either. Nevertheless, they were a part of my question for you to make yourself clearer about what you expect. So now I know that you don’t expect the Vietnamese to accept both Eurocentric and Sinocentric views of the world, yet you expect them to follow example of “good scholarship” which means “human-centric” or “world-centric” scholarship.

Euro-/Sino- now swell up and become World-?

I don’t know who is in charge to determine what it means by “human” and “world” (I’m sure I’m in no position to do that for you and other fellows).

I said it does not matter for me where/when the tools come from but how they are used. Essentialism, orientalism, nationalism or whatever have no problem themselves but the intention of those who use them that matters. Tran Ngoc Them’s works are acceptable as his arguments have not been used to justify mistreatment, domination, violence, aggression against others but to give himself and the Vietnamese an explanation, a guide to cope with their new environment in which their old traditions were falling apart and swallowed up (death of Confucianism, upset agricultural life..)

On the other hand, similar theories and ideologies were employed to justify exploitation, slavery and extermination of local/aboriginal people (the Europeans/Americans did a good job finishing all the Indians, the Confucian imperialists to a lesser extent and degree tried to 教化 everyone around them with 禮樂)

They all claimed to have fanciful ideas: 仁義, 禮樂, democracy, objectivity..

Money, culture, education per se have no good or bad but the intentions to use them to help (as others want not as one wants) or to impose/attack/inflict that matter.

Now you want to bring “good scholarship” to this land?

I’m not an essentialist/substantialist for sure. I do not see any essence in anything. I do not see people becoming smarter or scholarship getting better either. I see 變化 not 進化 (changes not developments/advancements)

I’m not sure if I’m as perceptive as fellows around me but I do not want/expect/need/demand them to be anything.

What I would expect is that in the 21st century a country of close to 100 million people (i.e., clearly not limited in its human potential) with a long history of valuing education would not teach people at the university level information that is based on ideas that have clearly been demonstrated in other parts of the world to be flawed.

By “good scholarship” I mean simply scholarship that is based on ideas that can be defended (at least more than any alternative at the moment). I don’t think there is anything culturally specific about that. If I make point A and someone demonstrates that evidence 1, 2 and 3 show that point A is not true or is not accurate, and you put forth point B and people either can’t find any evidence that proves that it’s inaccurate, or they have some evidence that just modifies your point a bit, then point B is clearly “better scholarship” than point A. I think that is a universal human concept. No one thinks that a point that has lots of evidence against it is better than a point that doesn’t have evidence against it.

So concepts like racialized explanations of human culture, essentialized explanations of human culture, etc. are now all examples of “bad scholarship” because scholars have shown over and over that these approaches to explaining human societies are flawed.

This is why students in places like Europe/North America are not taught racialized or essentialized explanations of human societies anymore. It has nothing to do with the intent of the authors/teachers/professors. It is that the ideas are flawed. They do not accurately describe reality, and therefore, cannot be used effectively to put forth ideas (however positive those ideas might be) about reality.

But yes, I agree that TNT probably had a good intent when he wrote that book, but by basing his ideas on flawed concepts (“bad scholarship”), I think his good intent backfires.

What does he say about the Viet? They are peaceful, kind, flexible, etc. How does he make that point? By creating an essentialized dichotomy between the Viet and “Others.” So if the Viet are peaceful, kind and flexible, then through the use of this essentialized dichotomy, other people are violent, inflexible, etc. (and he literally says this).

Is that an accurate description of reality? Of course not. Is it helpful to teach people that they are “good” and other people are “not as good”? I would say that it is definitely not a good idea because 1. this teaches people something about themselves and others that is false, and 2. (in the case of how this is done in TNT’s book) it “equips” them with ideas about society and the world which are also false.

I say this because I think that the goal of education is to make people more intelligent and perceptive so that they can succeed in life (on multiple levels), but as far as I can tell, that’s not what this book does. It teaches people that they are “special” (and again, the evidence used to make that claim is based on ideas that have been discredited in other parts of the world through valid means – by presenting tons of information that concepts like racialized/essentialized explanations of human societies are not true/accurate), and at the same time, it gives people a completely outdated and distorted understanding of how to think about human societies.

And finally, to get back to that idea of “good scholarship,” again, I don’t think that it is culturally specific. It is universal. However, in the case of something like the study of human societies, there is no denying that from say 1960 to the present there has been much more effort to study and understand human societies outside of Vietnam than there has been inside of Vietnam.

As a result, now that Vietnam is “integrating” into the world, when someone in Vietnam puts forth point A now, s/he has access to a lot of information about point A, including a lot of information that might disprove point A.

So should s/he ignore that evidence and just go ahead and make point A because s/he has a good intent?

I would say “no,” because I think the goal of producing knowledge is to make people more intelligent, and when there is evidence that shows that your ideas are flawed and you ignore that information and go ahead and say something else, then you are not making people more intelligent.

I don’t think and didn’t say that anyone should ignore anything to attach to Tran Ngoc Them’s explanation. What I did say is that he provided an explanation with which I disagree but I recognise it as an understandable explanation (there are many other arguments including yours with which I also disagree but still recognise them)

I also pointed out that he never used the theories/concepts to justify mistreatments, aggression, domination, exploitation of other people as the racist supremacist colonizers/invaders did/have been doing. That was to show how ironic it is to try to expose his “racism”.

More importantly, that was to stress the intention & purpose not the tools themselves that matter. It is due to the fact that similar theories/concepts (however badly “flawed” or excellently “proved/demonstrated” they are) can be used either to help people or to justify murder/stealing.

Anyway, if you really earnestly aspire to see what is there and the ultimate satisfaction, I recommend treading beyond the boundary of scholarship. I see that education/learning/life are not limited to and can not be reduced into, identified with the pursuit of success and intelligence which are but coming and ceasing phenomena.

I recognize that TNT’s book provided an understandable explanation for a Vietnamese audience in the mid-1990s. However, the world and Vietnam have changed dramatically since then, and at this point I see that book, which continues to get reprinted and used in universities, as both an embarrassment and an obstacle to enabling people to look at the world realistically.

I think that there are many people who realize this, however they don’t always have the academic background to see in what ways the text has problems. I wrote those posts to enable such people to see how someone from North America with an academic background might “deconstruct” the ideas in that book.

And while the book might not use theories/concepts to “justify” mistreatments, aggression, domination, exploitation of other people, it would be easy to demonstrate how it hides, or avoids discussing, mistreatments, aggression, domination, exploitation of other people through the theoretical approach that it takes. (this is another major topic in “Western” academic critiques of domination of all kinds, and is often referred to by sexy terms like “erasure,” i.e., by not talking about negative points, you “erase” them)

The introduction to American society/history textbooks that students in the US are assigned do not avoid talking about mistreatments, aggression, domination, exploitation of everyone from Native Americans to Vietnamese (although I’m sure that there are people who would argue that they should say more), but the theories in TNT’s textbook inform us that wet-rice growers are peaceful, so therefore there is no mistreatment, aggression, domination, exploitation of anyone. My reading of Vietnamese history, however, suggests to me that this is not entirely accurate. . .

Therefore, I don’t see anything ironic in what I wrote. What is, I think ironic, is that I constantly see these days that for some reason only Westerners are seen as racist/dominating, etc. However, as far as I can tell, those are also universal phenomena. Before Westerners colonized places in Asia, there had already been plenty of mistreatment, aggression, domination, and exploitation there (and this all continues today in one place or another).

What is unique, is that it is only in “the West” that people have criticized their own societies for these “bad traits.” People in other parts of the world are happy to continue down the path that “Westerners” created and criticize “the West” for these things, but for some reason, they never seem to want to look into the mirror at themselves. TNT’s book is a perfect example of that – the West is aggressive and violent, the world of the Viet is peaceful, etc.

As for recommending that I tread beyond the boundary of scholarship, thank you very much for the encouragement. Maybe writing a blog and responding to comments gives the impression that I am locked in an ivory tower somewhere and never come out. Nothing, however, could be further from the truth.

I already spend most of my time on other things – spending time with family, making music, films, etc. However, I don’t think one needs to separate scholarship from life. The two can, and should, intersect and reinforce each other.

As for “success,” I think the definition of that term varies from one person to another. For me, “success” is having a life where I have a roof over my head, food to eat, and can learn something new every day, so right now I am a very successful man.

And as for the “intelligence” that I gain along the way, yes, whatever comes will one day cease, but the printed word can make that “intelligence” immortal, so I don’t plan on resigning myself to a Buddhist fate of non-action, as I do of course want to obtain immortality. 🙂

We’ve probably said all there is to say on this topic. However, if you have more to say, please do so. But just in case you don’t, I wanted to say that it has truly been a pleasure exchanging ideas with you.

“For me, “success” is having a life where I have a roof over my head, food to eat, and can learn something new every day, so right now I am a very successful man.”

Hey bro (or Prof), I just have had too much success in a week in Cuba: Big roof over my dead (you ought to see the Hotel :), food are everywhere I look and best of all I have a whole 391 pages of “Imperial China and Its Southern Neighbors”, to learn every day.

Thank you!

Wow!! Mr. President, I’m honored!!! I had no idea that you read this blog! Yes, I am aware of your your recent and historic trip to Cuba, but no one in the media mentioned that you were reading a book while you were there.

I’m not so sure that there is much to “learn” from that book, but it should be effective for putting you to sleep at night, which of course is very important for a president.

In any case, enjoy the final months of your presidency, and the next time you are in Hawaii, get in touch. We can “talk story” about history. I had no idea you were so into it . . . 🙂

無為而無不為

I don’t think anyone should and I did not recommend anyone to stop doing what “they are doing” to resign to a state of “non action” in which he/she sits in one place and do nothing/trying not responding to any stimulus.

Non/no action: 無為 is not a state to which one attaches. It is rather about the realization that there is no action, no actor, no doer, no thing done but phenomena appearing and ceasing dependently on impermanent conditions. One will not try to perceive/think/feel/enter “non/no action” as I was not referring to any object of the senses, any concept, any feeling, or any particular palatial/temporal place.

Of course, one still perceives/thinks/feels/comes and goes as he/she pleases: total/ultimate freedom, liberation, satisfaction. That is 無不為

So one should not be confused about the ultimate and the conventional as he/she got observation/insight/experience of this very moment of consciousness/reality, not just understanding on intellectual level.

Unless one is “unborn/not born”, he/she/it is bound to die. There is no immortality/eternity in a mortal/changing world. Nevertheless, the unborn/not dying nature of immortality can be realized.