I love the early twentieth century, as that is when the Vietnamese worldview started to change dramatically, and the documents from that period make that perfectly clear.

I’ve been writing about a fifteenth-century document known as the “Great Pronouncement on Pacifying the Ngô” (Bình Ngô đại cáo), and of course the question of what the term “Ngô” refers to has come up.

The limited evidence from the fifteenth-century makes it difficult to determine what exactly that term meant at that time, but early twentieth century writings make it very clear what the term meant at that time.

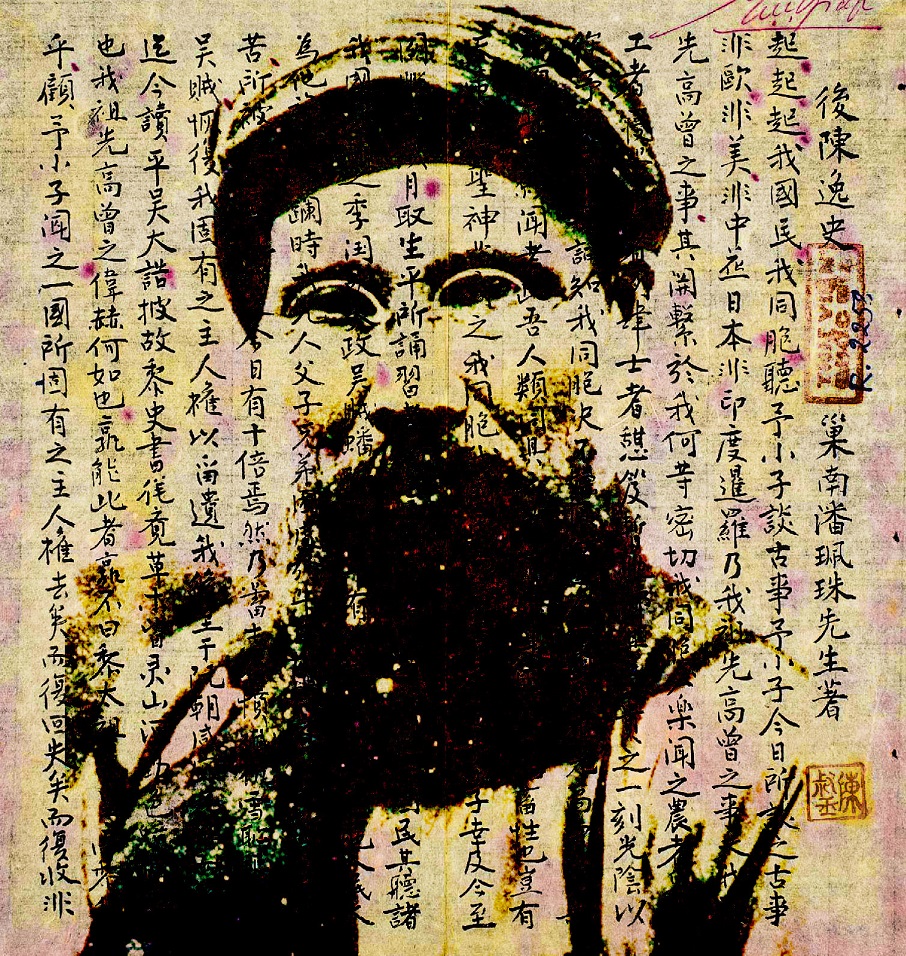

A case in point is an historical novel that Vietnamese revolutionary Phan Bội Châu wrote in classical Chinese in the early twentieth century called The Lost History of the Later Trần (後陳逸史 Hậu Trần dật sử).

What was the “Later Trần”? It’s complex, but essentially after Hồ Quý Ly usurped power from the Trần Dynasty, the Trần sent an emissary to the Ming court to ask for help, the Ming sent down an army, but that army didn’t put a member of the Trần royal family back in power (as they were supposed to do), and some members of the Trần royal family resisted the Ming, and this is known as the “Later Trần.”

Why did Phan Bội Châu decide to write an historical novel about this period? Clearly he was trying to instill a sense of nationalism in educated Vietnamese, and he was trying to get Vietnamese to resist the French.

Where did he get the ideas to do this? That is also clear – from Chinese revolutionaries like Sun Yat-sen and Liang Qichao, as his text totally repeats the type of language that was used in nationalistic Chinese writings at that time that sought to “awaken” China and to get the Chinese to resist the West.

“Rise up, rise up, rise up, my fellow citizens, my fellow compatriots,” is how the novel begins, echoing a phrase that was repeated many times in that time period by Chinese nationalists.

As for the term “Ngô,” it is the only term in this text used to refer to “the Chinese,” and it is used over and over. This starts at the beginning of the text when Phan Bội Châu states that the Ngô took advantage of the Hồ’s mistakes to take control, and with that, “the people from our land of the free were trampled on by another race.” (我自由之土地人民,大爲他族蹂躪)

All of this terminology about freedom and race was new. And my sense is that his usage of the term Ngô as the only term to refer to “China/Chinese” was also new.

But given that Lê Lợi is today the nationalist hero from that period, why didn’t Phan Bội Châu write about him? That is because Phan Bội Châu was a monarchist who wanted the Nguyễn Dynasty to continue. He therefore had no interest in glorifying a military man who betrayed a dynasty. That glorification came later, by people who were “anti-feudal.”

As such, the way that Vietnamese today think about the past is newer than the time when Phan Bội Châu thought about the past, but Phan Bội Châu himself also thought about the past in new ways as well.

What all of this means is that the way that Vietnamese think about the past today is far removed from the way that people in the past actually thought about the world they lived in. And that is why the early twentieth century is so important, as it shows us the point when the Vietnamese worldview started to change.

This Post Has One Comment

I came upon your website looking for the inefficiency and cumbersome writing system Chữ Quốc ngữ, with diacritics along with tones and came upon your website. “Story, narration” in Chinese is 故事,not 古事 as written incorrectly several times by Phan Boi Chau. Why did Mr. Phan write in Classical Chinese when he is a known advocate of Chứ Quốc ngữ? The dia critics were created by Europeans, while tones are from Chinese. Thank you for the interesting articles. I’m Chinese born in Vietnam. I’m learning Vietnamese via books and the internet. Also trying to match Vietnamese words to Hán-Nôm as much as possible. If it wasn’t for one of your articles I would have written Giám(監) in Quốc Tử Giám(國子監) incorrectly in Chinese. Thanks again.