In 1965 there was a coup in Indonesia. Sukarno was overthrown, and the coup was blamed on Communists. A purge of suspected Communists then ensued, and some half a million (maybe many more?) people were killed.

A few years ago, anthropologist Robert Lemelson made a documentary about that period called “40 Years of Silence: An Indonesian Tragedy.”

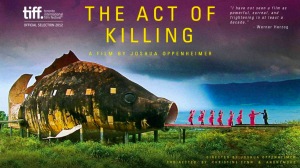

More recently, Joshua Oppenheimer has made a film about the same topic called “The Act of Killing.” I still haven’t seen this film, but it’s getting a lot of positive reviews.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9oebCcE6-k

To get a sense of what it deals with, the above piece by Al Jazeera called “101 East – Indonesia’s Killing Fields” is a good introduction.

The blurb on YouTube about the video states that “Executioners from Indonesia’s dark past speak out for the first time to reveal a chilling and bloody truth the country now has to face. 101 East speaks exclusively to some of those who participated in the systematic murder of millions.”

Then for Cambodia there is a series of TV shows that have been subtitled in English, such as “Duch on Trial” that documents what has happened in the ongoing war trials in Cambodia.

These trials are, of course, very limited. They are just trying the top Khmer Rouge leaders, however, the rank and file Khmer Rouge remain at large among Cambodian society.

That must create a great deal of stress for many people. It must be horrible to know that people who are responsible for killing ones relatives and friends are living normal lives.

In the case of Indonesia, there is clearly a sense of fear of what would happen if such stresses were allowed to be released. “The Act of Killing” has therefore been banned in Indonesia.

In the Al Jazeera piece, a member of the Islamic group, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), is interviewed. NU members were responsible for the killings of many suspected Communists in 1965, and this is what one member of NU said in the Al Jazeera video:

“We are worried. In this country, small things easily explode. What if this whole thing explodes again? What will happen to Indonesia if the 1965 case is opened up?”

This statement reminded me of a review I read of Huy Đức’s Bên Thắng Cuộc in which the reviewer basically said that the past is a book that should be closed. There is no need to revisit the past. People should just move forward and leave the past behind.

That is much easier said that done. Over 150 years after the Civil War in the US ended, the divisions that came to the fore at that time still, to some extent, remain, even though many people have tried hard to move beyond them.

What is the best way to deal with those issues? Is it to go back and look at them, as is happening to a limited degree in Cambodia? Or should the past be left in the past, as many have tried to do in Indonesia and Vietnam? Maybe something in between?

This Post Has 2 Comments

I don’t know what to say, do you have any legal proof on this? Indonesia is known as one of religious country, eventhough acts of some people didn’t shown that they’re “religious” or try to prove what they believe in the way they live their live. As a Catholic (and I believe most of non moslem too), a minority in this country I’ve my own opinion, NU or Nahdatul Ulama is one of the best friend. They are Moslem, but they have help us in many ways the other Moslem community can’t do. They have a deep understanding on how should we live, as a human. How should we give respect to other people who don’t have the same believe. Even Gus Dur, the most honourable man in NU (before he pass away), if I may say, is the only the man that able and dare to take action against racism in Indonesia.

Thank you for your comment.

I wasn’t making an accusation or argument in this piece. I was just simply asking a question about how to deal with the past.

You mention legal proof – that’s exactly what people in Cambodia have spent years (and probably millions of dollars) putting together just so that they can try in court a few of the top Khmer Rouge leaders.

Is that the best way to do things? Or do you let things that happened in the past just remain in the past and focus on developing what is good in the present?

Do either of these approaches resolve issues/heal wounds/make a society healthy? If not, is there a better way?

This is what I was asking. I don’t have the answer. As an historian, I don’t think that ignoring the past is a good idea, but at the same time, digging up the past can cause problems. But not dealing with the past also causes problems. So what do you do? I have no idea. That’s why I wrote this.

As for what actually happened in the past in Indonesia, I am certainly not an expert on that topic, and therefore have to rely on the work of others, but I don’t think I say anything in this brief piece that isn’t common sense/widely known in the academic world.

See, for instance, the following (and there are many other works that have talked about this topic):

“Nahdlatul Ulama and the Killings of 1965–66: Religion, Politics, and Remembrance”

Author

Greg Fealy and Katharine McGregor

Source

Indonesia, Volume 89 (April 2010), 37–60.

Abstract (English):

The essay examines the narratives Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) promulgated to explain its role in the mass killings of Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI) members in 1965–66. Drawing on interviews and documents, the authors describe the history of antagonism between the NU and PKI and the role NU members played in the killings. It also shows how the organization perceived and articulated Indonesian communists as a threat to the Muslim community and to Islam itself. In the second half of the article, the authors reflect on how the NU and individuals within the NU have dealt with the legacy of 1965 over the last ten years.