Alexander Woodside’s Vietnam and the Chinese Model (1971) is a pioneering work of scholarship that remains today an important study of nineteenth-century Vietnam and the Nguyễn Dynasty. Woodside was the first scholar in the English-speaking world to make extensive use of Nguyễn Dynasty sources and no scholar since has produced a work of scholarship that ranges so broadly over the nineteenth-century Vietnamese historical record.

Like any pioneering study, however, Vietnam and the Chinese Model can still of course be improved upon, and we can see this with regards to one issue that Woodside discusses in this work, the role of Nôm, or the demotic script, in early nineteenth century Vietnam.

The overall idea of Vietnam and the Chinese Model was that there was an identifiable “Vietnam” that was distinct from a “Chinese model” that the Nguyễn Dynasty sought to impose on it. More specifically, Woodside envisioned a world in which there was a “Southeast Asian” Vietnam on which a “Chinese model” of elite ideas and cultural and administrative practices was placed, and in his book he highlighted the ways in which he felt the Chinese model did not fit comfortably on that Southeast Asian reality.

Languages and scripts are one topic that Woodside discusses, however it is difficult to place the languages and scripts of nineteenth-century Vietnam in a dichotomous view of “Vietnam” and “China,” and Woodside struggled to explain the actual role of, and ideas about, languages and scripts in nineteenth century Vietnam. Here the big problem was determining what the role of Nôm, a demotic script based on Chinese characters, was.

On the one hand, Woodside stated that “nôm allowed Vietnamese writers to escape more successfully from the clichés of the Chinese classics than Chinese writers could, and it also enabled them to draw upon the folk literature of the common people,” which suggests that Nôm was something “non-Chinese.” (53)

But then on the other hand, Woodside also referred to Nôm as “a bridge by which Chinese meanings might entire Vietnamese verbal contexts,” which would mean that it was something at least kind of “Chinese.” (53)

So Woodside was a bit vague about what exactly the role of Nôm was but he depicted Nôm as a script that Vietnamese naturally sought to use in communications and that the imposition of the “Chinese model” by the Sinicized elite ended this.

He argues, for instance, that in the years of the Tây Sơn Rebellion in the late eighteenth century the civil service examination system had “moldered” and that by the early nineteenth century,

“. . . without the impetus of the examination system, many Vietnamese officials and their underlings had found it almost easier to remember Vietnamese characters than Chinese ones. In fact nôm was at the height of its popularity in the very early nineteenth century. Gia-long encouraged it, out of necessity if not out of desire.” (54)

Woodside then argues that this official acceptance of the use of Nôm was then reversed by Gia Long’s successor, Minh Mạng.

“Minh-mạng wasted little time in reacting. In the first year of his reign, 1820, he attempted to deal a death blow to nôm at the Huế court by ordering that from then on all memorials, and all compositions written at Vietnamese examination sites, be written in characters identical to those in the imported [Kangxi] dictionary. . . rather than in ‘confused rough scripts.’” (54-55)

Woodside states here that there were “Vietnamese” and “Chinese” characters, and that after the tumultuous years of the Tây Sơn Rebellion it was “almost easier” (another vague expression) for people to remember Vietnamese characters.

By “Vietnamese characters” what Woodside really means is “Vietnamese words written in Nôm characters.” It is true that there are words in Vietnamese that do not exist in Chinese, and that therefore, Nôm characters were created to represent those words.

However, Nguyễn dynasty officials never wrote documents that only contained Vietnamese words.

First, such words only constitute a small percentage of the overall Vietnamese vocabulary. A huge percentage of the Vietnamese language consists of words of Sinitic origin.

Second, because the educated elite in premodern Vietnam became literate by learning classical Chinese, they were familiar with set expressions in classical Chinese.

As such, for a Nguyễn Dynasty official to write an official document in nineteenth-century Vietnam, there wasn’t really a choice between using either Nôm or classical Chinese, because the Vietnamese language is filled with terms from Chinese, and because the premodern elite used classical Chinese expressions like writers in the West used to make use of Latin expressions.

To illustrate this point, think of an English sentence that makes use of many Latin terms and expressions.

Imagine, for instance, that someone wrote the English sentence “Since antiquity, soldiers have always been brave and faithful” as “Ab antiquio, militum have been semper fortis and semper fidelis.”

The only “English” words in this sentence are “have been” and “and.”

This is what Minh Mạng was opposed to. He wanted writings to be 100% in classical Chinese. This does not mean that officials had been writing 100% in Vietnamese prior to that point. Instead, what had been happening is that officials had been writing in classical Chinese and including some Vietnamese words, similar to the above sentence which we can imagine is written in Latin with some English words thrown in.

The text that Woodside cites for this information about Minh Mạng’s order in 1820 is the Quốc sử di biên, and it clearly states in that text that in the early years of the dynasty “[written] orders often mixed in the kingdom’s sounds [quốc âm].” (國初詞命多雜用國音)

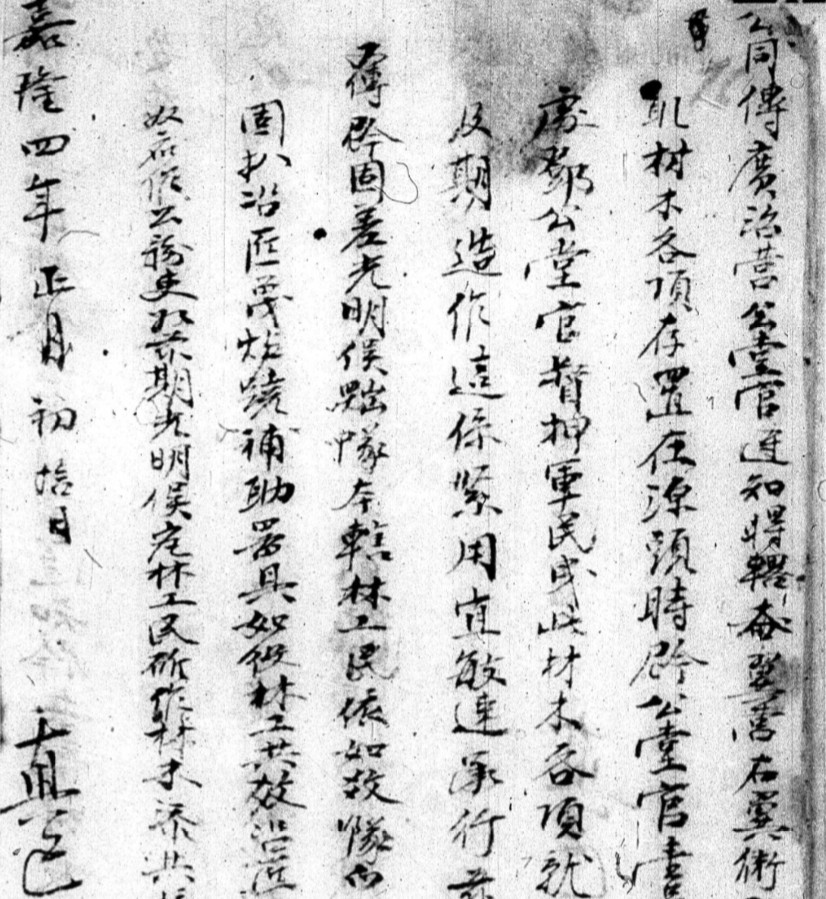

Today we refer to Nôm as a script, but the nineteenth-century Vietnamese elite viewed it as “sound” (âm 音), and they considered “sound” to be inferior to “writing” (văn 文). Classical Chinese was “writing. The “kingdom’s sounds” were not. This is an important distinction and the Vietnamese translation of this text diminishes that distinction by translating the “kingdom’s sounds” (quốc âm) as “Nôm characters” (chữ Nôm) (see the above image).

What Minh Mạng wanted was for writings to be completely in “writing,” and not to include any “sounds.”

What is more, he also wanted the calligraphy to follow a certain style – the style of the calligraphy of characters in the Kangxi Dictionary. (字畫一依康熙字典,不得用亂草本)

There are “variant” versions of Chinese characters (異體字), and Chinese characters can be written in a kind of cursive script (草字). In the early nineteenth century, there were Nguyễn Dynasty officials who wrote documents in the cursive script and who used variant versions of Chinese characters. Minh Mạng wanted officials to stop doing that.

In other words, Ming Mạng was not ordering his officials to write in “Chinese” instead of “Vietnamese,” as they were already writing in classical Chinese. What he ordered them to do was to “clean up” and “standardize” their classical Chinese writing by not inserting any “sounds” and by not writing in the cursive script.

Extant documents from this period make this evident. The first two images above are from documents dating from the Gia Long reign (1802-1819), and the last document above (in the tan color) is from Minh Mạng’s reign.

What should be obvious is that the writing in the document from the Minh Mạng reign is clearer and more standardized.

That is how Minh Mạng wanted his officials to write.

Again, it wasn’t a distinction between writing either in Nôm or classical Chinese. It was a matter of “cleaning up” and “standardizing” writing in classical Chinese.

To be fair to Woodside, he may have understood this and simply struggled to figure out how to explain all of this clearly (as I have struggled here to do so as well). However, I have definitely seen other scholars cite this passage from Woodside’s book and misunderstand it as talking about a clear distinction between writing in “Vietnamese” and writing in “Chinese,” and that Minh Mạng was “repressing” writing in Vietnamese in favor of writing in Chinese. That is not accurate.

On a larger level, however, this issue is also important as it has implications for the argument that there was a meaningful distinction between a (Southeast Asian) “Vietnam” and a “Chinese model.” That is a concept that has received a lot of support over the years, but this case of Minh Mạng reforming how official documents were written points to why it is problematic to envision such a clear distinction in this way.

[國初詞命多雜用國音,明命以來,始改用驣黃莊雅,場屋文章,及臣庶箋,字畫一依康熙字典,不得用亂草本,窽格尤詳。]

This Post Has One Comment

Có nhiều người cả ở trong lẫn ngoài nước Việt Nam cho rằng “quốc âm” (國音) là tên gọi khác của chữ Nôm, đây là một sự hiểu nhầm đã bị lan truyền quá lâu, “quốc âm” không phải chữ Nôm, “quốc âm” đồng nghĩa với “quốc ngữ” (國語), ở Việt Nam thời xưa nó là tên gọi đặc chỉ cái ngôn ngữ ngày nay thường được gọi là “tiếng Việt”. Theo như tôi biết thì có ít nhất là bốn tên gọi khác nhau được dùng trong văn bản Hán văn ở Việt Nam thời xưa để chỉ tiếng Việt, bao gồm “quốc âm” (國音), “quốc ngữ” (國語), “Nam âm” (南音), “Nam ngữ” (南語). Không biết tên gọi “tiếng Việt” bắt đầu được dùng để chỉ tiếng Việt từ khi nào, tôi không biết có văn bản nào được viết trước thời Pháp thuộc gọi tiếng Việt là “tiếng Việt”, có vẻ như tên gọi này cùng với “người Việt”, “người Kinh” mới chỉ xuất hiện và/hoặc được dùng theo cái nghĩa ta biết ngày nay từ thời Pháp thuộc.

Không biết ở Việt Nam trước thời Pháp thuộc đại bộ phận những người bản ngữ tiếng Việt có coi tiếng Việt và tiếng Hán là hai ngôn ngữ khác nhau hay không hay họ coi nó là một phương ngôn (方言) của tiếng Hán giống như tiếng Quảng Đông, tiếng Triều Châu, tiếng Khách Gia… ? Những từ ngày nay được gọi là “từ Hán Việt” được những người bản ngữ tiếng Việt có học vấn cao thời đó nhìn nhận như thế nào. Trong tiếng Việt thời kỳ đó có từ ngữ nào tương đương với thuật ngữ hiện đại “từ Hán Việt” (mới chỉ xuất hiện trong nửa sau thế kỷ XX) hay không? Tôi thấy trong sách báo tiếng Việt xuất bản trong nửa đầu thế kỷ XX dưới thời Pháp thuộc từ Hán Việt được gọi là “chữ nho”, “chữ Hán”, “Hán tự” và “chữ”. Các tên gọi này vừa được dùng để chỉ một loại văn tự (chữ Hán) vừa được được dùng để chỉ một loại ngôn ngữ (tiếng Hán) vừa được được dùng để chỉ các từ Hán Việt trong tiếng Việt, Không biết trước thời Pháp thuộc ba tên gọi “chữ nho”, “chữ Hán”, “Hán tự” đã xuất hiện trong tiếng Việt hay chưa, nếu như có thì nghĩa của chúng có bao gồm tất cả những nghĩa đã nêu ở trên hay không?