The Hùng Kings are an invention. They were not invented out of nothing, but instead were fashioned out of extant written sources. This process of creation, however, was not clean. A lot of literary debris was left behind, and this is extremely obvious in the way in which the Hùng kings came to possess a citadel.

The earliest recorded information about rulers in the Red River delta can be found in the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region (Jiaozhou waiyu ji), a Chinese work from either the late third or early fourth century A.D. This work is no longer extant, but passages from it are preserved in a sixth-century text, Li Daoyuan’s Annotated Classic of Waterways (Shuijing zhu). This is what it says,

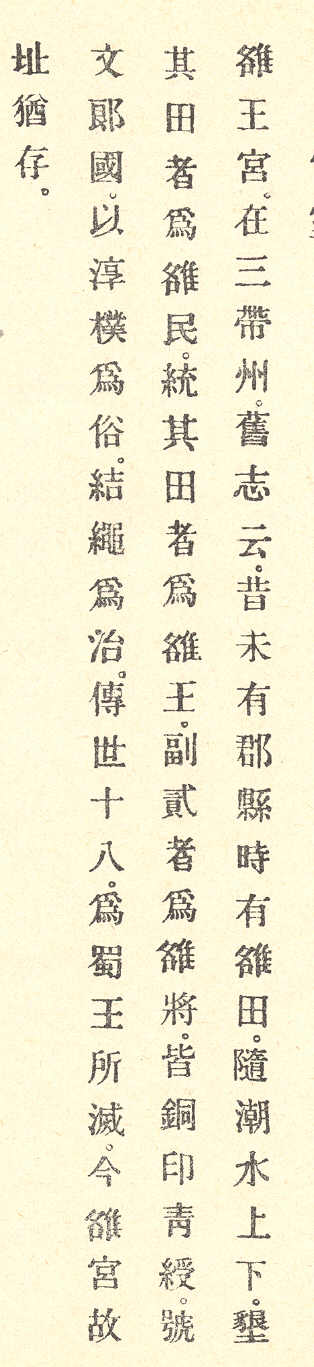

“The Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region states that ‘In the past, before Jiaozhi [Việt, Giao Chỉ] had commanderies and districts, the land had lạc fields. These fields followed the rising and falling of the floodwaters, and therefore the people who opened these fields for cultivation were called Lạc people. Lạc kings/princes and Lạc marquises were appointed to control the various commanderies and districts. Many of the districts had Lạc generals. The Lạc generals had bronze seals on green ribbons. Later the son of the Thục/Shu king led 30,000 troops to attack the Lạc king. The Lạc marquises brought the Lạc generals under submission. The son of the Thục/Shu king thereupon was called King An Dương. Later, King ofSouthern Yue [Nam Việt/Nanyue] Commissioner Tuo [i.e., Zhao Tuo] raised troops and attacked King An Dương.’”

Notice that this passage says nothing about “Hùng kings.” That is because the Hùng kings are a medieval invention. They were created in the fifteenth century, and incorporated into Ngô Sĩ Liên’s Complete Book of the Historical Records of Đại Việt (Đại Viêt sử ký toàn thư).

The above passage from the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region was one source of inspiration for the myth of the Hùng kings. Prior to the point where the myth of the Hùng kings was created, a myth started to develop about first Kinh An Dương and then the Lạc kings based on this passage from the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region.

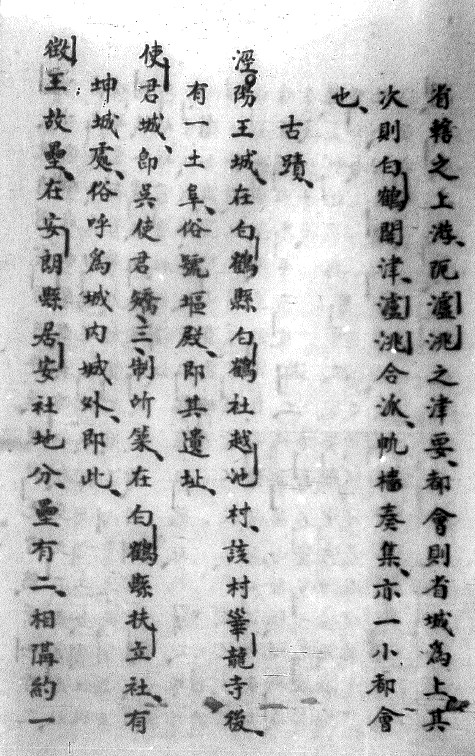

In a section on ancient remains (cỏ tích), the Brief Record of An Nam (An Nam chí lược), a text compiled in the fourteenth century by a Vietnamese who had switched sides during the second Mongol invasion and lived the rest of his life in China, has an entry on a place called “Việt King Citadel” (Việt Vương Thành) which cites the above passage from the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region.

This entry does not directly state who built or inhabited this citadel. Instead, it simply appends the passage from the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region, implying that this could have been a citadel built by King An Dương or perhaps Zhao Tuo. That said, it does indicate that this citadel was also called Khả Lũ Citadel by common people. Khả Lũ Citadel was another name for Cổ Loa, a citadel not far to the north of present-dayHanoi and which was reportedly built by King An Dương.

The fifteenth-century Treatise on Annan (Annan zhiyuan), a Chinese text which was compiled based on information collected during the Ming occupation period, also contains an entry for Viêt King Citadel in a section on ancient remains. However, the Treatise on Annan does not associate this site with the information about the Lạc kings and King An Dương from the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region. Instead, it connects that information to a separate site of ancient remains known as “Lạc King Palace” (Lạc Vương Cung).

At the same time, in its entry on Lạc King Palace, the Treatise on Annan adds some new information which the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region did not record. It states that “[The kingdom] was called the Kingdom of Văn Lang. Its customs were pure and simple. Records were kept by tying knots. Rule was passed on for 18 generations. It was destroyed by the Thục/Shu king. At present the remains of the Lạc palace still exist.”

Where did this new information come from? There is no way of knowing. However, the expression “records were kept by tying knots” (結繩為治) was a formulaic way of describing a pre-literate society. It is a sign that this information was not an actual account of a past society, but more likely the creation of a medieval scholar.

This exact same information later appeared in the official Qing Dynasty geography, the Unified Gazetteer of the Great Qing (Da Qing yitong zhi).

The remains of this Lạc King Palace which the Treatise on Annan mentioned were in what was at the time Tam Đái Subprefecture, an area which later became Vĩnh Tường Prefecture in Sơn Tây Province, far away from Cổ Loa where the information from the the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region had earlier been used to describe where some ancient remains had come from.

This idea that there were some ancient remains in Sơn Tây Province continued. However, over time they came to be associated with an earlier figure, the mythical King Kinh Dương (Kinh Dương Vương), rather than the historical King An Dương. In particular, in Sơn Tây Province’s Bạch Hạc Distict there was a mound of earth which people referred to as “King Kinh Dương’s Citadel” (Kinh Dương Vương Thành).

Then in the twentieth century, the Hùng kings “took over” that citadel. And they did so in a text called the Unified Gazetteer of Đại Nam (Đại Nam nhất thống chí).

The Unified Gazetteer of Đại Nam (Đại Nam nhất thống chí), was a geography which the Nguyễn Dynasty ordered compiled in the 19th century. It wasn’t fully completed until the early 20th century when it was to be printed. However, only part of the text ended up getting printed, and the section on Sơn Tây Province never made it into print.

Therefore, the information which that text contains about King Kinh Dương’s Citadel comes from draft manuscript versions of that text. This text was translated into modern Vietnamese in both South and North Vietnam. And while the translations differ, in both cases the Hùng kings came to take over King Kinh Dương’s Citadel.

This is what the version published in Saigon recorded (this is the only version which I have the Hán text for, which is what I am translating):

The abandoned citadel of King Kinh Dương. Behind Hoa Long Temple in Việt Trì Village, Bạch Hạc District there is a mound of earth. It is said that it is the remains of his old citadel.

According to the Unified Gazetteer of the Great Qing, it is said that “Hùng King Palace is in Tam Đái Subprefecture. [The quốc ngữ translation has “Lạc” here, as does the Unified Gazetteer of the Great Qing, but the Hán text of the Unified Gazetteer of Đại Nam has “Hùng.”]

The Annotated Classic of Waterways [states that], “Before Jiaozhi [Việt, Giao Chỉ] had commanderies and districts, there were lạc fields. These fields followed the rising and falling of the floodwaters. Those who opened these fields for cultivation were called Lạc people. Those who ruled these people were Lạc kings/princes. Below them were Lạc marquises [the character actually means “emissary” and is mistaken for a character meaning “marquis”]. [The kingdom] was called theKingdom of Văn Lang. Passed on for 18 generations, it was destroyed by the Thục/Shu king. The remains of the palace still exist.

According to the Historical Records [i.e., the Complete Book of the Historical Records of Đại Việt], “The Hùng king established his capital in Phong Region [Phong Châu].” Note, This is the same as Bạch Hạc Distict. We therefore suspect that this is the cite of the Hùng king’s old citadel, and that by popular custom it has been erroneously referred to as Kinh Kinh Dương’s citadel.

—–

Let’s try to summarize this information:

13th/14th century = The Brief Record of An Nam (An Nam chí lược) mentions a “Việt King Citadel” (Việt Vương Thành) in Cổ Loa which it appears to attribute to King An Dương. It cites the information from the the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region to support this claim.

15th century = The Treatise on Annan (Annan zhiyuan), also records that the remains of the Viêt King Citadel were in Cổ Loa, but it does not connect this site with the information from the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region.

The Treatise on Annan connects the information from the the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region to a place in Sơn Tây Province which it calls the “Lạc King Palace” (Lạc Vương Cung). It also includes new information that “[The kingdom] was called the Kingdom of Văn Lang. Its customs were pure and simple. Records were kept by tying knots. Rule was passed on for 18 generations. It was destroyed by the Thục/Shu king. At present the remains of the Lạc palace still exist.”

18th century = The Unified Gazetteer of the Great Qing (Da Qing yitong zhi) contains the same information about Lạc King Palace in Sơn Tây Province as the Treatise on Annan.

19th century = Local gazetteers for Sơn Tây Province which likely date from the nineteenth century mention a “Kinh Kinh Dương Palace” (Kinh Dương Vương Cung) but do not connect this place to the information from the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region.

Late 19th-early 20th centuries = The Unified Gazetteer of Đại Nam (Đại Nam nhất thống chí) cites the Unified Gazetteer of the Great Qing to indicate that the Lạc King Palace which it mentions is the same as the King Kinh Dương Palace which people in Sơn Tây Province speak of. This text also cites the information about Lạc people and kings from the the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region (by citing the Annotated Classic of Waterways where that information is preserved).

It then cites the fifteenth-century Complete Book of the Historical Records of Đại Việt to indicate that this is where the Hùng kings’ capital was, and that therefore this is the remains of the Hùng kings’ citadel.

Amazing! From King An Dương, to the Lạc kings, to King Kinh Dương, to the Hùng kings, and from Cổ Loa to Sơn Tây, the passage from the Record of the Outer Territory of Jiao Region was repeatedly used to attribute significance to ancient remains.

Why did this happen? It happened because that passage is the ONLY recorded information which we have about the early history of the Red River delta. Everything else, from King Kinh Dương to the Hùng kings, was invented. And because it was invented, it wasn’t rooted in any real tradition.

It is only in the twentieth century that the Hùng kings have become “real.” This acquisition of a citadel in the Unified Gazetteer of Đại Nam was an early step in that process.

This Post Has 7 Comments

I’ve often wondered about the Hùng Vưong too and took put much stock in the tales. I think it would be interesting to tell the story of the development of the Hùng Kings in the Vietnamese imagination over time. Another question, does archeology do anything to fill out this history?

Yes, I agree. The hard part is that people don’t know where to start, because people have not been sure about what is historical and what isn’t. If you look at the writings of Dao Duy Anh in the 1950s, for instance, he came up with all kinds of theories which tried to explain how someone like Kinh Duong Vuong (Lac Long Quan’s father) might actually have been at least imagined by people in the first millennium BC.

Archaeology – the problem with archaeology is that many archaeologists have used the information about antiquity in Vietnamese texts to talk about the materials they have found. What people need to do is to look at the archaeological material and explain it on its own, because it is not connected to the historical information. I’m not really up to date on what Vietnamese archaeologists are doing these days. I think some people do do this. However, I don’t think that there has been a clear de-linking of the information about antiquity in texts like the Dai Viet su ky toan thu with archaeology, as far as I know.

When I say that “the Hung kings are an invention” does not mean that there were no polities with rulers in the Red River delta in the first millennium BC. There obviously were. It’s just that the later written accounts were created in the medieval period, and are creations of the scholarly elite at that time.

I just finished reading the Keith Taylor book, actually. Neat stuff.

What did people find when they examined the oral traditions and folklores of the Muong people? Anything that could give clues to what pre-Chinese-domination Vietnamese polities were like?

Also – the knotted string thing – are there actually any Asian culture w/ that as a writing system? I keep thinking neat! like the Incas, but if that was just the Chinese way of dismissing a non-Chinese writing system, then never mind.

One thing you should be aware of is that Keith Taylor no longer believes a lot of the more nationalistic interpretations/statements that he made in that book. I think he is writing a general history of Vietnam. It will be interesting to see how he covers the early period now.

The problem with “oral traditions” is that they are not purely oral. Over the centuries, many elite written traditions have made it into the “oral tales” of common people.

A second problem is that many/most Vietnamese scholars believe that certain written information from say the 15th century is actually a record of oral tales which have been passed down since the first millennium BC. As I tried to point out in the post on where Vietnamese antiquity came from, this is not true.

So people have not accurately examine Muong oral tales because if they see anything in it which is the same as what Vietnamese wrote down in the 15th century, then they will conclude that this “proves” that that information dates from antiquity. In actuality, it just demonstrates that the Muong were in contact with educated people who passed an elite story on to them at some point after the 15th century.

As for the knots, the Chinese use that expression from I think the Zhou Dynasty period (1st millennium BC). The idea must have come from something/somewhere. I can’t imagine that it was just invented out of nothing. I would think that it would be something which some people in the area of what is today China engaged. I really don’t know that. It’s an interesting question.

Chào anh Khai. I just read the article and responses about “The Biography of the Hồng Bàng Clan” in JVS. Does that deserve an entry on its own? I was fascinated by the response from Tạ Chí Đại Trường. I was not aware of the contributions of French propagandists to the Hùng pantheon and their happy adoption by the Vietnamese regime. The article is concerned with a “medieval invented tradition” but reading all of these articles it’s not clear that historiography has yet left the medieval era in Vietnam. The primary of objective of history appears to be the creation of a state religion – miracles, saints and martyrs, a begat b, b begat c, consecration of holy sites… It would be like a pentecostalists writing the history of the United States (which they’re doing, but it is not taken seriously). Anyhow all four essays were very enlightening.

I agree, and yes I was amazed to read what TCDT wrote about the French. It makes sense. I definitely have never come across any reference prior to the 20th century for the “Death Anniversary of the Hung Kings.” Crazy!

Hi, Prof. Yu Insun (Korea) discusses nicely about the invention of Hung King in his article (published in Nhung Tran & Reid’s Borderless Histories).

AT