In 1980 a conference was held in Hanoi to mark the twentieth anniversary of the establishment of the Institute of History (Viện Sử Học). The topic of the conference was the question of when the Vietnamese nation formed (vấn đề hình thành dân tộc Việt Nam).

The opening address of this conference noted that this was an issue that had been discussed since 1955, and had been viewed in two main ways over that period of time.

In the period from 1955-65 there were some who closely followed Stalin’s definition of the nation, which argued that nations only emerged with the development of capitalist societies, and there were others who felt that there were pre-capitalist nations. In this period from 1955-65, the view that nations only emerged under capitalism (or socialism in the case of Vietnam) was the dominant belief.

Then in the period from 1965-80, but particularly from 1976-80, there was a push to recognize that the Vietnamese nation formed earlier than the emergence of capitalism/socialism in Vietnam.

At this conference, it was agreed that the Vietnamese nation emerged earlier than the capitalist/socialist period. However, the concluding remarks of the conference noted that:

“However, in order to resolve this question in an academic/scientific way, we still face a series of issues concerning theory and the historical reality of the nation that we need to continue to research more deeply and discuss more widely.”

Tuy nhiên, để giả quyết vấn đề một cách thực sự khoa học, chúng ta còn đứng trước hàng loạt vấn đề về lý luận và thực tế lịch sử dân tộ càn phải tiếp tục nghiên cứu sâu hơn nữa và thảo luận rộng rãi hơn nữa.

The conclusion of this conference was correct. Stalin’s definition of the nation is fine for describing a modern nation, but it does not describe communities that existed prior to the emergence of modern nations.

In general, this is an issue that Marxist theory did not discuss. Stalin did mention once (in 1950) that “nationalities” preceded “nations,” but he did not offer a definition of what a “nationality” was. (See this post for more on that topic.)

As far as I know, however, since 1981 Vietnamese scholars have not researched this topic further and come up with a clear definition of the type of community that preceded the modern nation in Vietnam. (If someone has, please inform me, I would love to read whatever that person/people wrote.)

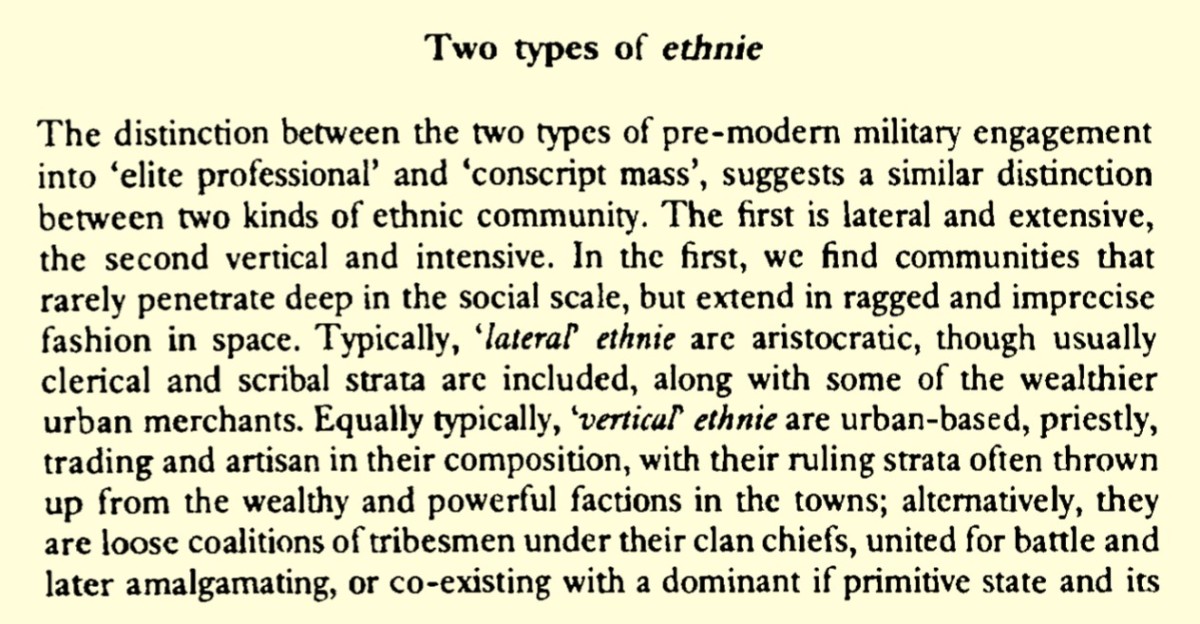

In the 1980s, however, this was a topic that British scholar Anthony Smith examined in detail in his The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Smith argued that prior to the formation of modern nations we can see something that he called “ethnie.”

This term is known by Vietnamese scholars today, however I have yet to see Vietnamese scholars recognize what Smith actually meant by that term. I see this term used by Vietnamese scholars as a general term for something that came before the nation (dân tộc), but Smith had specific definitions of ethnie.

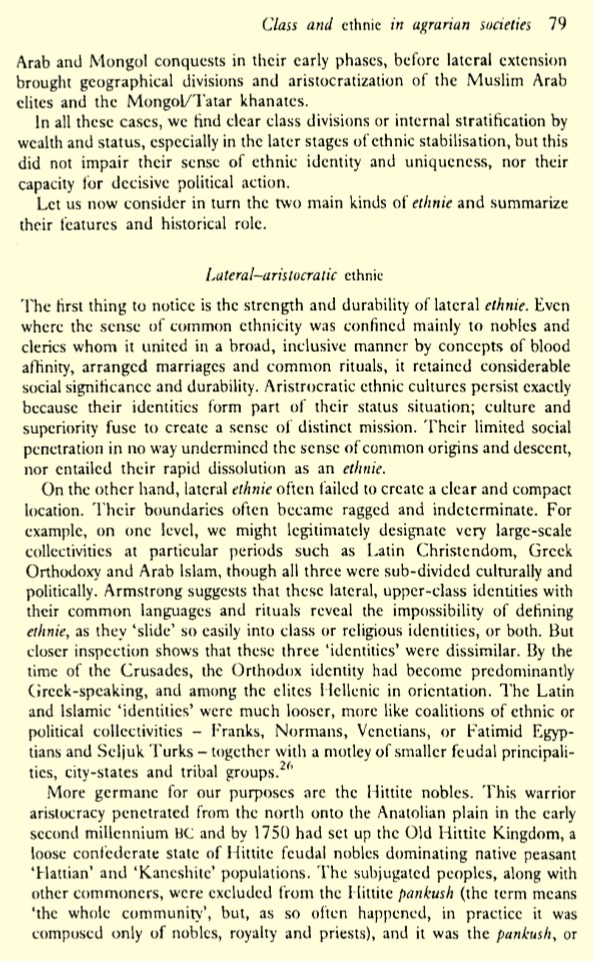

In fact, Smith argued that there were two different kinds of ethnie: a lateral-aristocratic ethnie and a vertical-demotic ethnie.

The lateral-aristocratic ethnie was a group that distinguished itself in opposition to the common people in their own kingdom/country. They did this through various means, such as by using a language that the common people did not understand (Latin, Sanskrit, classical Chinese), by controlling a religion, and through inter-marriage.

As for the vertical-demotic ethnie, this was a group that united everyone from the elite to commoners, and this is how Smith says that it happened:

“In contrast to the more fluid and open aristocratic type of ethnie, demotic or vertical communities emphasize the ethnic bond that unites them against the ‘stranger’ or ‘enemy.’ This entails a marked emphasis upon sharp boundaries, with bans on religious syncretism, on cultural assimilation and even on inter-marriage.”

If we look at premodern Vietnam, it is obvious that we can see the existence of a lateral-aristocratic ethnie. The premodern Vietnamese elite saw themselves as participants in a universal “Hoa” (“Chinese”/civilized) cultural world. They read and wrote classical Chinese. They wore the same robes as Han-Ming officials, etc. That is 100% a lateral-aristocratic ethnie.

And while there were times when the Vietnamese and Chinese worlds came into conflict, it never reached the point that would allow a vertical-demotic ethnie to emerge (not, that is, until the second half of the 20th century).

If we take China as the “stranger” or “other” that the Vietnamese defined themselves against, then at the elite level we do not find evidence in premodern Vietnam of “a marked emphasis upon sharp boundaries” with the Chinese world. Instead, we find the opposite.

It is therefore obvious that if we are going to use Smith’s idea of an ethnie to look at premodern Vietnam, then clearly we can see the existence of a lateral-aristocratic ethnie.

This is important because Smith did exactly what the 1980 conference in Hanoi on the formation of the Vietnamese nation called for: he researched further into what forms of communities existed prior to the emergence of the modern nation, and he produced a very detailed, and well documented, study on that topic.

I don’t see any reason to question what Smith wrote. What remains to be done then is to apply Smith’s ideas to the study of Vietnamese history. When we do that, we find that there is a great story that we can tell, and that is the story of how “Vietnam” transformed from a world that was dominated by a lateral-aristocratic ethnie into a modern nation.

This is, after all, precisely the kind of scholarly work that the call at the end of the 1980 conference for continued research urged scholars to undertake.

For anyone who wishes to read the report from that conference, here it is: 1980 nation conference report.

This Post Has One Comment

The lateral-aristocratic / vertical-demotic divide even has contemporary relevance in today’s United States and Vietnam. In the U.S. today we see a renewed impulse against internationalism and toward an isolationist nationalism. There is a kind of fluidity always in play. But your larger point is important – at a certain point an “aristocracy” in Vietnam was discredited (or at least was shown to be ineffective) so a new aristocracy came into being that knew it would have to rely on the demotic world and make it a part of its vision of the nation. But the overall impulses of those governing Vietnamese society remains lateral-aristocratic. This deserves the serious study that you advocate.