Yesterday the New York Times had an article on a new scholarship that is being created that will enable non-Chinese to study in China.

“The private-equity tycoon Stephen A. Schwarzman, backed by an array of mostly Western blue-chip companies with interests in China, is creating a $300 million scholarship for study in China that he hopes will rival the Rhodes scholarship in prestige and influence.”

The Rhodes Scholarship is a prestigious scholarship that supports study at the University of Oxford. So does the creation of this new scholarship indicate that the work of scholars in China is now on the same level with that of their counterparts in places like the UK? Are Chinese scholars now equal players in the international world of scholarship (whatever that means)?

I was wondering about that this morning when I visited the blog Tiếng vọng Kattigara and saw a translation there of an article that Li Hui, a professor at Fudan University, wrote entitled, “Common Origin of the Austronesian and Daic Populations.” This was a conference paper that was published in a journal called Communication on Contemporary Anthropology, “a peer-reviewed open-access journal both for professional and public authors.”

I am interested in trying to understand how the various peoples who today inhabit Southeast Asia got there, and where they come from, etc., so I decided to read this article. The abstract states that “In this paper, we found a close relationship between the Austronesian and Daic populations in the south of East Asia, and reconstructed the phylogenesis of the two population groups using paternal Y-chromosomes and maternal mitochondrial DNA.”

So it is a paper that employs information obtained from DNA to examine the past. I don’t know much about this, so I can’t really evaluate this type of scholarship, but I decided to read the paper anyway.

When I actually read the article, I found that it contains no footnotes, no references, and no discussion of methodology. At the same time it is extremely detailed. Here is an example:

“During the time from five to three thousand years ago, Min-Yue in Fujian and Nan-Yue in Guangdong were polarized, and gave birth to some new groups migrating out of the core region. These new populations were usually called Ou, which meant the outside people. Eventually, the Eastern-Ou migrated northward out of Min-Yue to south Zhejiang, and the Western-Ou traveled westward out of Nan-Yue to Guangxi. The Western-Ou mixed with the Luo-Yue and became the ancestors of the Zhuang-Tai. At about the same time period, the Kadai went northwest to Guizhou and founded several Kingdoms such as Yerong (Ye-Lang). They assimilated a large number of Phu aboriginal populations there, whose mother tongues were Proto-Austro-Asiatic. These findings were determined based on the duality of the Kadai genetic structure.”

This is all extremely problematic. Li Hui is completely uncritical in his use of the names of polities and peoples that we can find in ancient texts, like Nanyue and Ou (“Ou” meant, “the outside people”? To whom? How do we know that?). In other places he does the same with assemblages of archaeological artifacts (Liangzhu, etc.). Li Hui also connects current ethnic groups with past peoples, something that scholars in places like North America have argued against for decades by now.

Given that Li Hui does precisely the type of things that scholars outside of China dismiss, I am certain that this article could never get published in a place like North America, and yet Li Hui has published in North America.

In particular, he wrote an article on a similar topic – “Paternal Genetic Affinity between Western Austronesians and Daic Populations” – that was published in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology. Actually, Li Hui was one of several authors of this article, but apparently he worked with others to carry out “the molecular genetic studies,” he “participated in the design of the study and [together with others] performed the statistical analysis,” he helped collect the samples, and he “read and approved the final manuscript.”

Unlike the article published in China, this article has extensive footnotes, the methodology is clearly explained, and it does not use ancient terms like Nanyue, Minyue, Ou, etc. It is a completely different type of study (in both content and quality), even though it is about essentially the same topic.

Here it is interesting to note that the “chief advisor” of Communication on Contemporary Anthropology is Li Jin, a geneticist whose work on the mummies from the Tarim Basin has also not been uniform. He has talked of an “East Asian lineage” that one can find in the DNA of these mummies in some contexts, but not when publishing in North America (This blog post talks about this issue to some extent.).

So what is going on here? Are Chinese scholars duplicitous? Or is this just what they have to do in order to survive?

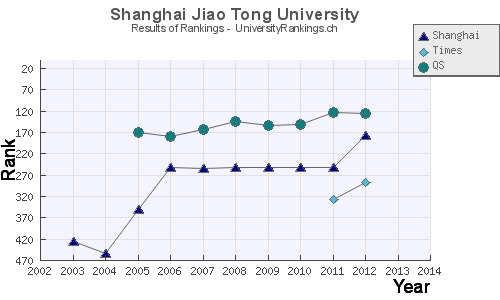

The proposed new scholarship that I mentioned at the outset of this post is something that I’m sure the Chinese government desperately wants. When it comes to education and scholarship, countries in Asia are trying so hard these days to gain ranking and prestige. But in the case of China, and some other places, this is taking place in a society that simultaneously works very hard to control education and scholarship.

So I’m wondering if Li Hui’s two articles are a sign of where all of this is going. Chinese scholars will produce strong studies that will get published in places like North America, Australia and the UK at the same time that they will publish rubbish at home.

This all seems so inefficient. People will grow up learning rubbish, and then at some point will have to un-learn what they have learned, so that they can then learn something new so that they can produce “international quality” scholarship. But at the same time that they do that, they will still have to remember the rubbish that they grew up learning because they will still have to publish more of that at home.

There has got to be a better way.

This Post Has 6 Comments

u know back in my learning mandarin days I was friends with a senior undergraduate in Beijing, his final thesis paper was to translate an English research journal into Chinese and nothing else. My German friend and I were looking at each other and thought to ourselves “WTF, is this the state of Chinese education today!”

btw, there are now many Confucius institutes all over the world spreading the “love” that is CCP propaganda. We are living in strange times 🙂

My guess would be that some professor who couldn’t read English wanted to be able to read that article. . . 😉

Thank you for touching on this subject. I dont see whats the problem here? Everything looks like its backed by solid scientific data (molecular genetics-dna).

Thanks for the comment.

The problem that I’m pointing out is with the article that was presented/published in China. I don’t think that there is a problem with the article that was published overseas (although I’m sure experts will probably have suggestions and perhaps critiques).

What I was pointing out was that in the China article the author uses ancient names as if they unproblematically refer to identifiable populations. No self-respecting archaeologist, anthropologist or historian outside of China would do that. And this author doesn’t do it either in the article that he contributed to that was published outside of China (why doesn’t he?).

Molecular genetics can of course challenge or overturn the ideas of archaeologists, anthropologists and historians, but this author doesn’t provide any “solid scientific data” to support what he says in that article. And again, in the “international” article, he doesn’t use those terms.

What this author writes in the article published in China fits into a long history of nationalist interpretations of the past. For decades now scholars in the PRC have more or less been attempting to “prove scientifically” that the world of the PRC was already there way back 2,000 years ago. The “nationalities” that the PRC (at times politically) categorized in the 20th century can all be clearly found in ancient sources, etc.

No archaeologist, anthropologist or historian outside of China buys this. And the fact that I don’t see evidence of these ideas in the article that was published outside of China, suggests to me that scholars who work in molecular genetics do not buy it either (because there is no evidence to support it).

So yes, I agree that the article that was published overseas “looks like its backed by solid scientific data” (and I say “looks” simply because I don’t have the expertise in molecular genetics to challenge it). However, the article from China provides no scientific data, and engages in the extremely promlematic exercise of uncritically employing terms from texts written 2,000 years ago.

In the end, I’m not criticizing this person’s abilities, because the article published overseas indicates that this person is doing precisely what his counterparts across the globe are doing. What I’m criticizing is the fact that he has to say something different within China.

I’ve noticed the same thing as well Mr. Minh, till this day China still wants to believe that they have evidence of the “mystical” Xia dynasty. Evidence points that Xia dynasty might of been a group of human settlements (villages) by the riverside. Studies like Genetics, Archeology, anthropology are based too much on a nation’s past “glorified/imagined” history, instead of looking at scientific data for what it is. It does not which country it is China, Vietnam, Korea, Japan, SE Asia, etc. being bounded by an “imagined” history is dangerous. Sadly, most of research grants are funded by national gov’ts and this truly hinders unbiased research.

Hypothetically, if we found out that Mongoloids were descendants of proto-Negritos and that there were certain diseases that they share would medical researchers would like to know to create new treatments. But, again there are people out there who want to “hide” facts because it goes against the status quo; in this case Asians may not like to hear their closest genetic relative maybe Negritos. On the other hand, ppl would support any scientific evidence if it supports their own “status-quo” version of national history.

Very good points!! And I totally agree with you. Once people hear that something is based on “genetic science,” they tend to think that it is “fact” and “unquestionable.” However, that is not true at all. From what I understand, the results of genetic studies can be seriously distorted by the choices that scholars make in selecting their test populations (that they base their studies on). There is no doubt but that genetic science can help us tremendously in our effort to understand the past, but we haven’t really reached the point yet when it is doing so in an unbiased manner.