I have been trying my hardest not to comment on Ben Kiernan’s recent book, Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. However, a sense of morbid curiosity keeps leading me to open the covers of that book, and each time I look inside I can’t believe what I see (this is after all a book published by Oxford University Press in 2017).

For instance, I recently opened the book to the following passage (pg. 173):

“The first extant text written in Vietnamese was composed in 1282, in the nôm script. Its author, Nguyễn Thuyên, addressed this poem to crocodiles that had appeared in the Lô branch of the Red River, and Emperor Trần Nhân Tông ordered the text thrown in the river in the hope of driving the reptiles away.”

Kiernan then provides a translation of this poem, and states that “This poem makes the first allusion in any Vietnamese text to ancient ‘Hùng kings’” and that “This was also the first attested use of the Vietnamese term for their land, nước Việt (literally, the ‘Việt waters’).”

That is a lot of “firsts”: the first extant text written in Vietnamese, the first allusion in any Vietnamese text to ancient “Hùng kings,” and the first attested use of the Vietnamese term for their land, nước Việt.

I consider myself to be an historian of premodern Vietnamese history, and yet I was unaware of any of these “firsts,” so I decided to look into the issue.

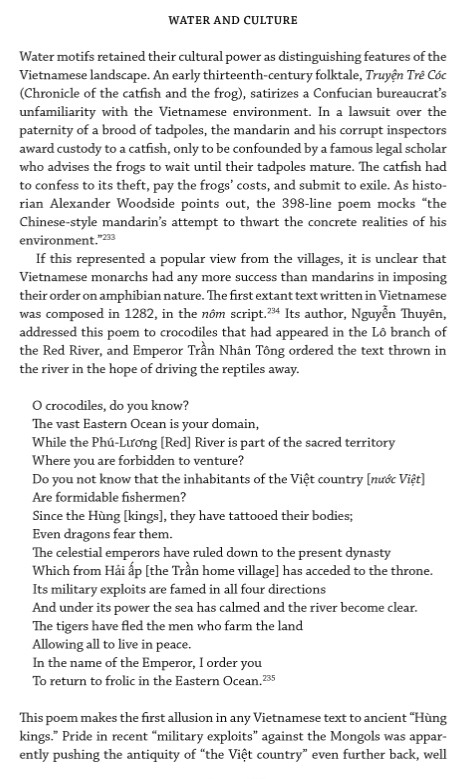

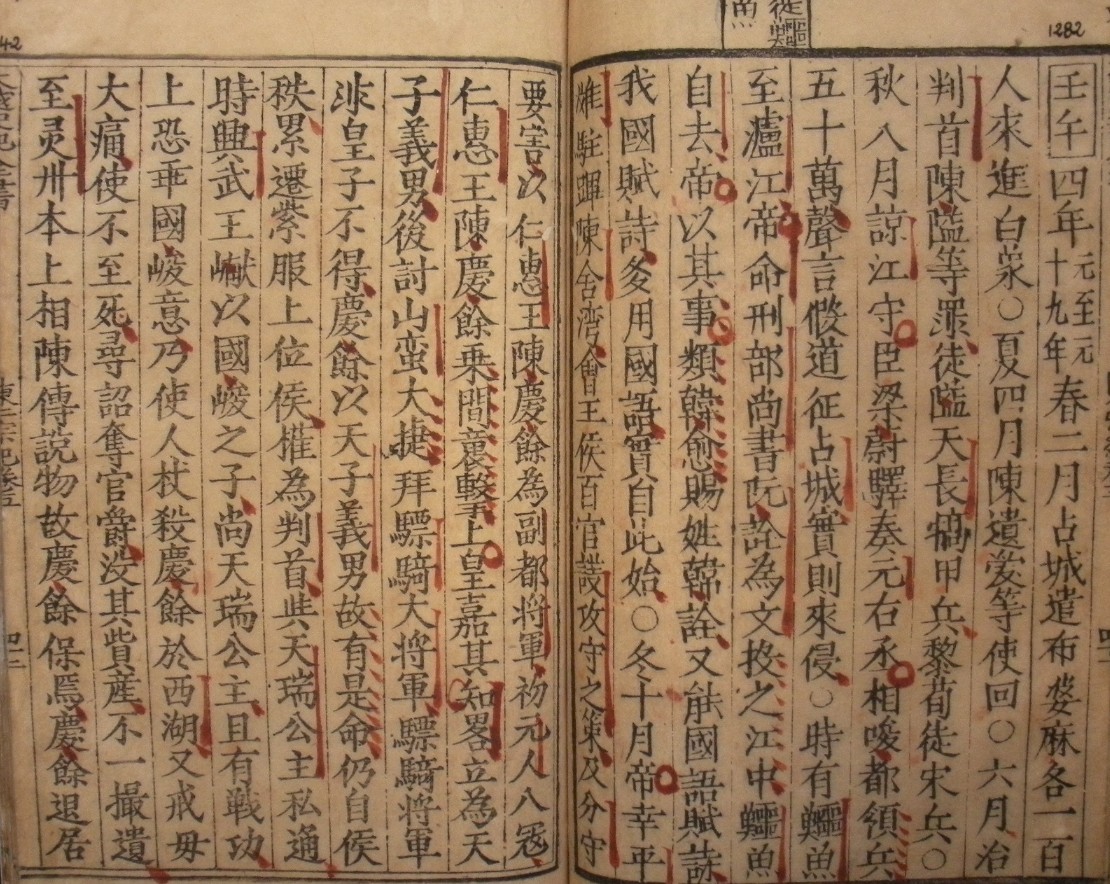

The Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư 大越史記全書 (Complete Book of the Historical Records of Đại Việt) is the earliest source to contain information about this event and it states the following:

“At that time [1282] there were crocodiles that reached the Lô River. The emperor ordered Minister of the Ministry of Justice Nguyễn Thuyên to compose a document [văn 文] and throw it into the river. The crocodiles then left on their own.

“The emperor saw this event as similar to that of Han Yu [Việt, Hàn Dũ] and granted [Nguyễn Thuyên] the name Hàn Thuyên.”

The Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư then states that, “[Nguyễn Thuyên] was also adept at rhyme-prose and poetry in the national language [hựu năng quốc ngữ phú thi 又能國語賦詩]. Our kingdom’s rhyme-prose and poetry makes much use of the national language. This truly started from that time.”

Bấy giờ có cá sấu đến sông Lô. Vua sai Hình bộ thượng thư Nguyễn Thuyên làm bài văn ném xuống sông, cá sấu bỏ đi. Vua cho việc này giống như việc của Hàn Dũ, bèn ban gọi là Hàn Thuyên. Thuyên lại giỏi làm thơ phú quốc ngũ. Thơ phú nước ta dùng nhiều quốc ngữ, thực bắt đầu từ đấy.

So the first point that we can see from this passage is that the document that was offered to the crocodiles and the fact that Nguyễn Thuyên composed poetry in the Vietnamese vernacular are two separate matters.

This passage does not indicate that the document for the crocodiles was written in the Vietnamese vernacular.

There is also no evidence that the document written for the crocodiles is still extant.

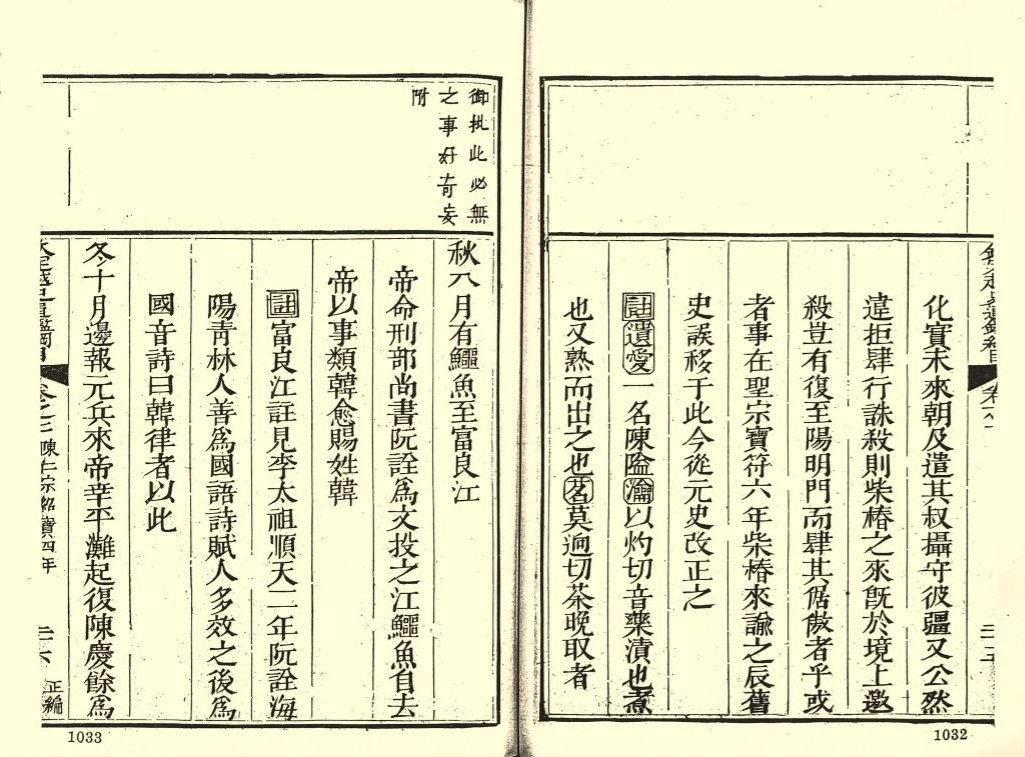

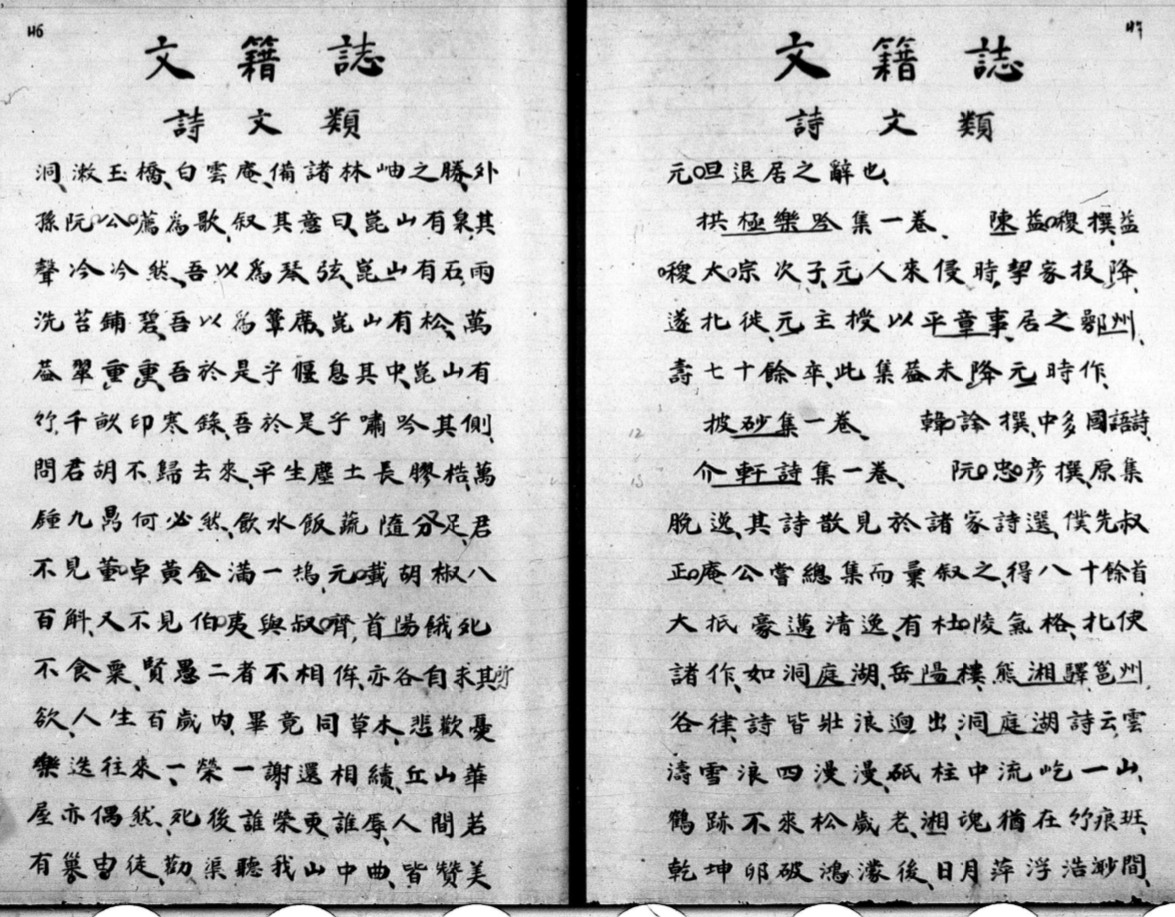

In the early nineteenth century, scholar-official Phan Huy Chú recorded in his Lịch triều hiến chương loại chí 歷朝憲章類誌 (Categorized Records of the Institutions of Successive Dynasties) that there was a poetry collection by Hàn Thuyên (Phi sa tập 披沙集) that contained many poems in the Vietnamese vernacular.

That collection, however, is no longer extant.

In the twentieth century when various Vietnamese scholars tried to determine when the Vietnamese demotic script, Nôm, first emerged, they all made note of this passage about Nguyễn Thuyên being “adept at rhyme-prose and poetry in the national language,” but they did not see clear evidence that the document for the crocodiles had been written in the Vietnamese vernacular.

In his 1941 Việt Nam văn học sử yếu (Outline History of Vietnamese Literature), Dương Quảng Hàm stated that:

“With regards to the document that was thrown down [into the river] to drive away the crocodiles, the historical text does not record what literary style it was written in or if it was written in Chinese or Vietnamese. Therefore we should not rush to conclusions like the common opinion that this document was a sacrificial essay in Nôm. Only when we find the original document will we be able to resolve this issue, but at present that document cannot be found in any book anywhere.”

Về bài văn ném xuống sông để đuổi cá sấu này, sử không chép rõ là viết theo thể văn nào và làm bằng Hán văn hay Việt văn; vậy ta cũng không nên vội cho – như ý kiến thông thường rằng bài ấy là một bài văn tế và viết bằng tiếng nôm. Chỉ khi nào tìm thấy nguyên bài văn ấy mới giải quyết được vấn đề ấy, mà hiện nay thì bài ấy không thấy chép ở sách nào cả.

Then in a 1959 work, Nguyễn Đình Hoà stated that the document for the crocodiles was “allegedly written in chữ nôm.”

[“Chữ Nôm the Demotic System of Writing in Vietnam,” Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 79, No. 4 (1959): 270-274.]

I’m not sure who “alleged” that or who was behind the “common opinion” in the 1940s, but from these comments by Dương Quảng Hàm and Nguyễn Đình Hoà we can see that there was some effort in the mid-twentieth century to claim that this document for the crocodiles had been written in vernacular Vietnamese, even though there was no historical evidence for that, and even though there was no historical document that recorded this text.

Ultimately, however, there was no need for evidence and no need to find an original document, because by the 1960s an “Essay in Sacrifice to the Crocodiles” (Văn-tế cá-sấu) had emerged. Kiernan cites a 1966 collection of French translations of Vietnamese literature by Dương Đình Khuê in which this essay appears in French and in Vietnamese.

Dương Đình Khuê does not indicate where he got this document from. However his use of the term “văn-tế” (essay in sacrifice) is interesting, as that relates to the information that was recorded in the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư where the emperor likened Nguyễn Thuyên’s driving away of the crocodiles to Han Yu’s earlier example of doing the same thing.

In the early ninth century, Tang Dynasty official Han Yu performed a ceremony to banish crocodiles from Chaozhou, in what is now the eastern part of Guangdong Province. He offered a sheep and a pig to the crocodiles and then placed in the water a document called the “Document for the Crocodiles” (e’yu wen/ngạc ngư văn 鱷魚文).

After doing so, the crocodiles departed.

When this “Document for the Crocodiles,” was later included in a famous seventeenth-century literary collection (the Guwen guanzhi 古文觀止), it was renamed as the “Sacrifice to the Crocodiles Essay” (Tế ngạc ngư văn 祭鱷魚文).

So why is it that when a document that no one in Vietnam had been able to find for years suddenly “appeared” again it also carried a new name, and one that resembled the “modern” name of Han Yu’s text: the “Essay in Sacrifice to the Crocodiles” (Văn-tế cá-sấu)? Who named it that? That’s not what it is called in the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư.

Could it be that this document was a modern invention? If it’s not, then where is the original text that Dương Đình Khuê’s transcription into quốc ngữ and translation into French came from? No one has ever found such a text. The “Essay in Sacrifice to the Crocodiles” (Văn-tế cá-sấu) is therefore likely a later fabrication, and my guess would be that it is a recent fabrication (twentieth century).

As such, I think it should be clear by this point that the three “firsts” that Kiernan lists likewise do not exist.

There is no first extant text written in Vietnamese dating from 1282.

The first allusion in any Vietnamese text to ancient “Hùng kings” does not date from 1282.

The first attested use of the Vietnamese term for their land, nước Việt does not date from 1282.

Beyond these factual errors, however, the entire premise that Kiernan employed this incorrect information to support is also flawed. The passage in the book that deals with Nguyễn Thuyên’s effort to get rid of crocodiles is meant to show that there is an enduring “aquatic” theme to Vietnamese culture, as this is one of the main points that Kiernan attempts to demonstrate in his survey of Vietnamese history.

However, all we can really see from that event is a highly literary (and Sinitic) approach to dealing with issues.

A couple of centuries before Nguyễn Thuyên wrote a document for the crocodiles, Song Dynasty Buddhist scholar, Qi Song 契嵩 (1011-1072) had criticized Han Yu’s earlier effort to drive away crocodiles by writing to them.

Qi Song stated that “Crocodiles are a kind of unknowing insect. How could they have understood Master Han’s text?” (鱷魚乃昆蟲無知之物者也,豈能辨韓子之文耶?)

Clearly Nguyễn Thuyên had more faith in the written (Sinitic) word than Qi Song did. That is not the sign of an identification with some kind of “aquatic” or “water” world. It is a sign of a deep attachment to an elite, literary, and Sinitic world.

Similarly, the emergence in the twentieth century of an “Essay in Sacrifice to the Crocodiles” (Văn-tế cá-sấu) is likewise a sign of a deep attachment to an elite, literary, and Sinitic world.

Although it was composed in modern Vietnamese, the fact that it emulates the way that Han Yu’s text was known to people at that time (through the popular Guwen guanzhi) is evidence of a continuing elite connection with the elite, literary, and Sinitic world (and that’s not surprising for 1960s South Vietnam).

Kiernan is in way, way, way, way over his head in this book. And by diving deep into waters that he has no ability to swim or even wade through, the book that he has produced sinks Vietnamese history into the depths of an earlier age.

It is going to take a lot of time and work to elevate premodern Vietnamese history out of those depths that this has book placed it in.

This Post Has 8 Comments

I wonder when the Sông Lô crocodiles were driven to extinction? (Could it have been from indigestion?) It’s usually impossible and I think unnecessary to makes claims for “firsts.” Especially when the surviving documentary evidence is so thin. But you are so right that it becomes outright foolish when one cannot read or judge the small amount of evidence that is extant.

Yea, the text says that they “reached” or “arrived at” the Lo River, so another question might be “where did they come from?”

As for your other point, I was able to locate 2 of the three sources that the author cites (the other was a workshop presentation) and both of them talk about this issue in their opening passages, and neither of them make the claim that this was the first extant Nom text, etc.

So it is also odd to make such a claim when the sources you cite do not make that claim.

I guess I’m also asking myself – have paleontologists found crocodile bones nearby? Have archaeologists found crafts or tools made of crocodile bone, teeth or skin? I had never thought of crocodiles as being part of Vietnamese material culture or folklore. Could the crocodiles have also not existed, but were invoked solely for the purpose of the lessons of the 9th century text you cited?

Apparently this “Văn Tế Cá Sấu” was first introduced in 1941 by Nguyễn Can Mộng in “Tứ Dân Văn Tuyển” and claimed that it was written by Nguyễn Thuyên. Trần Văn Giáp later opined that Nguyễn Can Mộng made up the whole thing! Dương Đình Khuê only translated the piece.

Of course, if we look at the words used in the “poem” (yes it was in the form of a poem, not an essay), they are too new to be 13th century words. For example, “biển Đông”, “vua Hùng”. Those are words that today Vietnamese use.

However, I think most Vietnamese today, provided that they know about this poem, would strongly believe that Nguyễn Thuyên was indeed the author and that it was written in Nôm.

By the way, who is/are on the book review board for Oxford University Press?

Thanks for this!! Do you know where Trần Văn Giáp said this?

And yes, you are exactly right about the words in the poem. They are very modern.

As for Oxford University Press. . . this is one of countless similar problems that can be found in this book.

Here it is:

http://giaitri.vnexpress.net/tin-tuc/sach/lang-van/nguyen-thuyen-va-van-hoc-nom-1974289.html

dustofthewest – good question!! You got me thinking, and the new blog post is in some ways an effort to answer your question of where crocodiles actually were.

_ the same thing is read differently . For Pr Kelly , Hàn thuyên ‘s Văn-tế cá-sấu shows the influence of Sinitic culture on vietnamese scholars . The nationalists see it as the symbol of the spirit of Vietnamese culture striving for independance . I think , it’s a misguided thought , arising from ignorance ; Văn-tế cá-sấu is supposed to be the first

nôm work written in chữ nôm or in quốc ngữ . They think that proves an independant spirit , because they think it’s all written in non Han words and there ‘s an airtight separation between chữ nôm (or quốc ngữ ) and Han characters . In reality , one cannot write anything whether poem or prosa without some Han viet words . Anyhow , the different styles of writing whether poetry , phu’ , hich , cáo , tế are under Sinitic culture influence .

Moreover , I think that in those times , it’s impossible that one should not write in wen yan ( văn ngôn ) ; so Văn-tế cá-sấu as we know it must be a forgery or the nôm translation of a work written in wenyan

The nationalists are panting to prove their narrative . For example , Hô quy Ly when he took power enacted a lot of

reforms but they latch only on one : his use of chữ nôm in official documents . They ignore the fact that he pretended to come from mythical ” chinese ” emperor Thuấn and renamed Đại viêt as Đại Ngu ( same country name as used by Thuấn ) , he wanted to be more “chinese” than “chinese”

_ non- wenyan litterature is called quốc âm ( instead of nôm literature ); Nguyễn Trãi wrote many works in quốc âm

VN scholars officially wrote in wen yan ( văn ngôn , belles-lettres ) and they dabbled also in quôc âm for leisure ; quôc âm is generally considered as a minor literature .

_ quốc ngữ nowadays is understood as popular talk , vernacular ( in China , it’s called bai hùa 白話)

_ guoyu ( quốc ngữ ) in chinese culture is the pekinese pronunciation ( vahicular) of chinese characters

_ chữ quốc ngữ = latin transcrition ( no national script )