Last week an article repeatedly appeared in my Facebook feed. It is a critique by a Vietnamese photographer (Hà Đào) of the works of a French photographer (Réhahn) based in Vietnam.

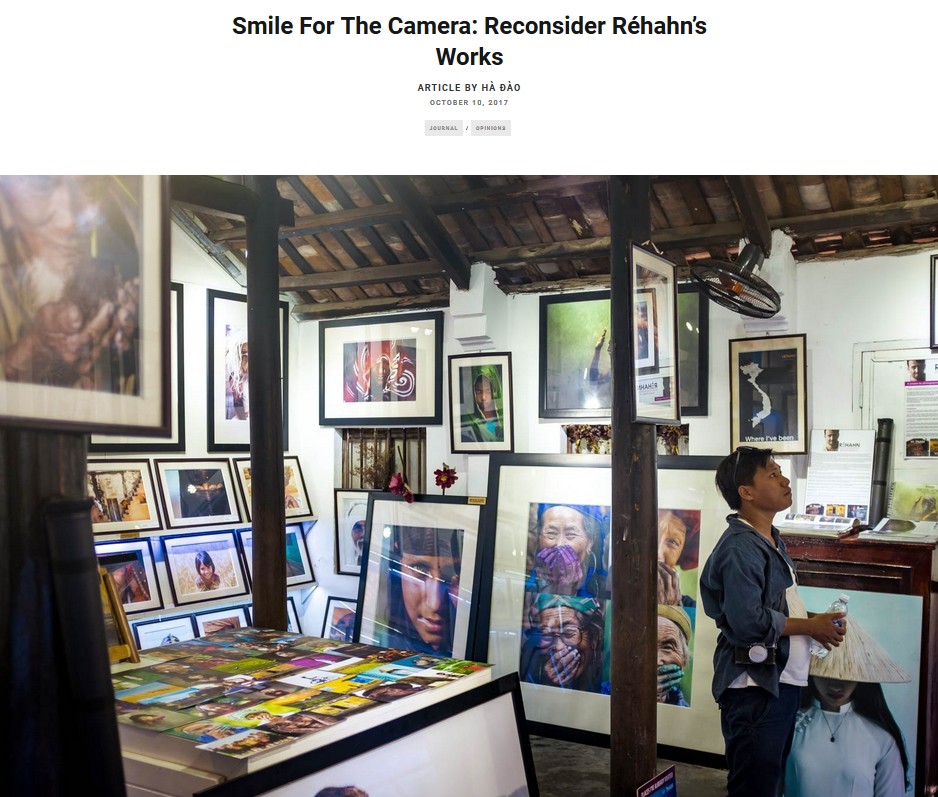

Entitled “Smile For The Camera: Reconsider Réhahn’s Works,” the article has received lot of attention, and has been both praised and criticized.

I was unfamiliar with the work of both Hà Đào and Réhahn, so I tried to learn what I could from the Internet, and then after I had done so, I read the article.

In reading the article, I found that I really liked the author’s critique, and the eloquent manner in which it is made, but that I was also dissatisfied with some aspects of the author’s argument, and that made me think about how we can make such a critique more insightful.

Réhahn has apparently been producing photographs of Vietnamese subjects for years, and he now has a couple of galleries in Vietnam where he sells his works. Many of his photographs are of minority women and children, and they apparently are popular and sell well.

These photographs, as Hà Đào explains, are romanticized images, but that does not seem to bother her all that much as she notes that this is not unique to Réhahn’s work. As she explains, “In Vietnam, romanticizing ethnic cultures has a long history, from established Vietnamese Association of Photography Artists to young road-tripping-with-a-bike travel photographers.”

Instead, what bothers Hà Đào is “the world view reinforced by Réhahn’s carefully curated portfolio.”

What is that worldview? It is one that ignores the modern present and places Vietnam in a pre-modern past. To quote,

“. . . Réhahn’s work thrusts me into a time-warp to a Vietnam prior to when modernity knocked on our doors. What is most stereotypical of a pre-modern Vietnam has to be present. The Vietnamese wear ao dai and conical hats, the M’Nong tames elephants, the H’Mong works on terrace fields. . . Flying thousands of miles from France to Vietnam, Réhahn also chooses to fly back in time to a country without motorbikes, cellphones and livelihoods other than agriculture.”

From what I have seen of Réhahn’s photographs, this seems to be a valid critique.

Hà Đào then goes on to link the worldview in Réhahn’s portfolio to phenomena such as Orientalism, colonialism and whiteness.

To quote, she states that,

“His romanticization, persistent pursuit of ‘authenticity,’ and portrayal of an Asian country through the lens of the past amounts to Orientalism, especially owing to his position as a white Frenchman. On the faces of old women and little kids in rural, mountainous areas with little doubt about the Western photographer’s intent, Réhahn projects his colonialist fantasy.”

There is a Vietnamese version of this essay, and its wording in this passage is more subtle. Rather, than saying, for instance, that Réhahn’s romanticization, etc. “amounts to Orientalism,” Hà Đào writes in Vietnamese that she “finds it difficult to not make a connection to the ideas of Orientalism of Edward Said” (tôi khó mà không liên tưởng đến tư tưởng Đông phương học [Orientalism] của Edward Said).

However, regardless of how this passage is worded, by bringing in “Orientalism,” “white Frenchman” and a “colonialist fantasy” here, I would argue that Hà Đào misses an opportunity to offer a more sophisticated critique of Réhahn’s photography, as those concepts are inadequate for critiquing the work of a Western photographer in the twenty first century like Réhahn.

Instead, to critique photographs like those that Réhahn produces requires that we come up with more nuanced concepts that can more accurately explain phenomena in the world today.

After reading this article, I went and re-read parts of a fabulous dissertation on twentieth century Cambodian art – the late Ingrid Muan’s 2001 PhD dissertation from Columbia University entitled “Citing Angkor: The ‘Cambodian Arts’ in the Age of Restoration 1918-2000.”

On a trip to Cambodia to 1992, Muan observed how Cambodian artists were hard at work producing paintings and replicas of Angkor Wat. This was the time when the United Nations was in Cambodia preparing the country for democratic elections.

The production of forms of art that celebrated traditional Cambodian culture fit with the UN’s mission to restore stability to Cambodia and it was also supported by Cambodian officials as they saw the potential for Angkor Wat and traditional Cambodian culture to attract foreign tourists.

Muan refers to this effort at that time on the part of certain Cambodians and members of the international community to promote Angkor Wat and traditional Cambodian culture as “Restoration Culture.” Further, she writes that she “had initially thought that the contemporary Restoration Culture was simply a replication of a colonial project pursued with the same scale and producing the same effects” (6), however through her research she came to realize that this was not the case.

In the first two chapters of that work, Muan writes about the colonial period, and focuses on the activities of George Groslier, a French artist who was recruited by the colonial administration in Cambodia in 1917 to establish an art school and art museum in Phnom Penh.

Groslier had actually been born in Phnom Penh, but he grew up in France. In the early twentieth century he returned to Cambodia where he researched and wrote a book about Cambodian dance. In the process, Groslier came to believe that Cambodian society in general, and traditional Cambodian arts in particular, were being destroyed by the presence of the French and Western culture.

Muan quotes the writings of Groslier to show that he believed that the Cambodians were a people who had been “immobilized for centuries” (23) but after coming into contact with the French, they started to rapidly change.

Again quoting Groslier, she writes that “The native who, since the time of Angkor, had need of nothing and received nothing from the West, living by his own resources and through his own means, suddenly discovered that he had all kinds of needs: a pair of shoes, a watch, a sparkplug, a yard of English crepe, a bicycle, a hat.” (25)

And as elite Cambodians sought out these contemporary Western products, Groslier stated that they ceased to sponsor the artists who had long produced Cambodian forms of art.

In response to the destruction that he believed the contact between Cambodians and the French was causing, Groslier did not advocate an end to the French presence or to colonial rule, but instead, he sought to “rescue” traditional Cambodian arts. This is what the colonial administration gave Groslier the authority to do in 1917.

A year later, in 1918, Groslier established the School of Cambodian Arts. The Wikipedia entry for George Groslier cites Muan’s dissertation for quotes by Groslier about how he insisted that the students in this school learn from Cambodian masters rather than French teachers.

While Groslier did indeed claim that this was the case, Muan notes that the curriculum for this school was essentially created by Groslier and his French assistants who determined what “designs” from traditional Cambodian art students needed to learn, and then those students studied by copying those designs.

Further, what Groslier wanted Cambodians to learn to produce were not paintings (so they were not producing works like the paintings of Angkor Wat that Muan saw being produced in the early 19902), but mainly carved objects that could be purchased by French and Cambodian officials and tourists.

In other words, Groslier sought to “save” traditional Cambodia art from following Western trends and modernizing by determining himself what “traditional” Cambodian art was and getting young Cambodians to learn his version of “traditional” Cambodian art.

How do we describe what Groslier did? Was it a form of Orientalism? Not really. Orientalism refers to the process where Europeans created a discourse about the Orient that depicted it as exotic and inferior. This “established knowledge” about the Orient then supposedly was used to justify Western conquest and colonization in order to “civilize” and “uplift” the East.

Groslier wrote about a Cambodia that had already been colonized. He did not try to justify colonization. Instead, he was critical of what he believed colonization was doing to Cambodia and its arts.

To cite a passage from Muan’s dissertation in which she repeatedly cites from Groslier’s article, “La fin d’un art” [The End of an Art] in Revue des Arts Asiatiques, 1929-1930:

“‘The European colonist,’ Groslier wrote knowingly, ‘was not a spectator’: he did not simply ‘contemplate the landscape.’ Instead, he quickly penetrated into the remotest areas and there engaged in ‘unceasing activity.’ The aims of the European were ‘never, let us note, to maintain the Cambodian plan [and] to defend the local traditions, but always to uproot them.’” (23)

Groslier did not want that to happen.

Further, the Orientalist discourse depicted Asian societies as static and unchanging. What Groslier saw was the opposite. He saw a Cambodia that was rapidly Westernizing. And while Orientalist discourse depicts the West as superior to the East, and in so doing, provides the West with supposed legitimacy to transform the East, Groslier and some of his contemporaries felt that not all that was Western was worth emulating, and that the aspects of Western culture that Cambodians were adopting were precisely the aspects that should not be adopted.

Muan makes this point clearly when she cites the work of one of Groslier’s contemporaries (and friend), Henri Marchal, a French official who was placed in charge of the conservation of Angkor Wat in 1916.

To quote:

“Already around 1910 Henri Marchal had observed ‘a certain degeneration, a beginning of decadence’ in ‘the motifs of the most recent art’: ‘the influence of the West, and models of deplorable taste introduced by cinema, illustrated magazines, and trinkets in the market, had made themselves felt amongst artisans used to transmitting from father to son, by tradition, ancestral motifs in which the art of Angkor was reflected.’

“Passing easily” from the local and traditional to a ‘mixed style of Chinese, Japanese, or of European forms,’ Khmer artisans transformed themselves into ‘copyists of the European,” producing ‘miserable failures’. . .” (27)

Can we call Marchal’s ideas “colonial” or “Orientalist”? He was critical of what colonialism was doing to Cambodian society, so how can he be “colonial”?

Yes, he wanted Cambodians to “stay in the premodern past” and keep producing traditional art, and that strikes us today as “Orientalist.” However, it is also clear that Marchal looked down on Western popular culture, and that he saw traditional Khmer culture as superior to Western popular culture.

We can thus get the sense that if Marchal were in France he would not be spending his free time going to watch movies, as many people in Cambodia and France were doing, but instead would only go to see performances of classical music, opera and ballet.

That is more “elitist” than “Orientalist” or “colonial.”

This brings us now to a key point: “Westerners” (like everyone else in the world) are not homogeneous in their beliefs and actions and never have been. Therefore, we have to think carefully before we use terms like “Orientalism” and “colonialist.”

Those terms have been used to refer to certain aspects of the “Western tradition,” but do they apply to Groslier and Marchal?

I would argue that people like Groslier and Marchal engaged in something that we can call “Colonial Liberal Orientalism.” Their ideas can be seen as “Orientalist” in the sense that they saw Cambodia (prior to its contact with France) as static and unchanging, however their ideas were also “liberal” in that they were critical of colonialism (rather than trying to legitimate colonialism). Nonetheless, they also held some colonial-era beliefs, such as the belief that Cambodians could never really be the equals of Frenchmen, and they did not actually call for an end to colonial rule. As a result, their ideas were also to some extent “colonial.”

In the post-colonial era, I would argue, “Colonial Liberal Orientalism” has transformed into “Liberal Orientalism.” Liberal Orientalism is a mode of thought that has emerged in the West since the 1960s. It has roots in the desire of the counter culture of the 1960s (the hippies) to find “spirituality” in “the East,” and in their critique of Western capitalism and consumer culture.

Like Orientalism and Colonial Liberal Orientalism, Liberal Orientalism also imagines an unchanging traditional Asia. However, rather than arguing that traditional Asia needs to be “transformed” by the West, as Orientalism did, or “rescued” from the popular culture of the West, as Groslier (and others) did, Liberal Orientalism holds that the West needs to be “saved” by traditional Asia, a world that (the people who follow Liberal Orientalism think) was not tainted by the capitalism and consumer culture that is destroying the West.

From what I can see of Réhahn’s photography, and like Hà Đào, I also feel “unsettled.” However, what unsettles me is not that his work is “Orientalist” or “colonialist” or that he is white (I’m not convinced that whiteness really matters here, but I’m also white. . . so I’m probably never going to convince anyone of that. . .).

What unsettles me is that his photographs appear to be part of a phenomenon that people do not clearly understand or recognize yet. I’m not sure if Liberal Orientalism fully captures that phenomenon, but I think it gets us much closer than “Orientalism,” “colonialism” and “whiteness” do. And I think it would be great if Hà Đào and others could dig deeper and really try to understand what the photographs of Réhahn really represent.

Finally, and importantly, Hà Đào also critiques the Vietnamese who promote Réhahn’s exoticized/romanticized photographs of ethnic minority women and children. This is important, and likewise deserves to be examined further.

To quote, Hà Đào states that,

“Réhahn’s work receives praise for its deep appreciation of Vietnamese beauty. Because more than ever Vietnam tourism industry needs postcard-appropriate pictures heavy in symbolism, and isn’t the recognition by a foreigner so life-affirming?”

The importance of “recognition by a foreigner” is a phenomenon that is often traced back to certain colonial (or post-colonial) complexes, but in the case of Vietnam I think that there is another layer to this issue, and one that is perhaps more significant, and that is the need to know that foreigners “love Vietnam.”

My guess at the moment is that this need/desire comes from the period of the Vietnam War and its aftermath. North Vietnam in the 1950s-1975, and then the Vietnamese state in the immediate post-1975 period, desperately needed allies and verification of its cause.

While this need/desire was particularly intense for Vietnam, this was a phenomenon that was part of the Socialist culture of the Cold War years as well, as Socialist nations repeatedly expressed their support for each other (as a student in the Soviet Union in the 1980s I drank to many toasts with my comrades to “the brotherhood” between country A and B).

Foreign visitors to Vietnam in those years were few in number, and hearing that they “loved Vietnam” was comforting and was widely disseminated through the media. That practice continues to this day (either out of habit or out of need/desire), and I would argue that the “life-affirming” recognition from a foreigner that Hà Đào refers to is at least in part related to this phenomenon that I refer to as the “I love Vietnam fetish.”

I’ve written a lot here, but that is because I have been inspired by Hà Đào’s article. I hope that people who are interested in this issue will perhaps gain at least a tiny bit of inspiration from this blog post and try to come up with ever more sophisticated and nuanced concepts for critiquing the present than concepts like “Orientalism” and “colonialism” enable us to do.

There are definitely things today that deserve to be critiqued, but for that to be effective and meaningful, we all need to be as insightful and accurate as we can possibly be.

This Post Has 4 Comments

That is a great critique. I think it goes beyond foreigners loving Vietnam. I think there is a fear that the beauty and uniqueness of the country and its people is not as well appreciated as it should be. The anxiety comes from seeing that the creative achievement of Vietnam are not viewed as taking part as an equal in the global cultural field. Along those lines we have all the concern with getting the “intangible cultural heritage” recognized.

Your coinage of liberal orientalism is great. There is a tendency to want to find some kind of timeless wisdom in the “primitive” / “exotic” other. This urge leads to wanting to protect the other from the decadence of the west — adopting western dress, lifestyles, consumer interests, popular culture, etc…

To further understand the phenomenon that this photographer represents it would be interesting to know whether Vietnamese people purchase his photographs as well.

Yes, the “UNESCO Recognition Fetish” is yet another issue. I’ve always held a more cynical view of that and see it in economic terms. Every province wants something on the UNESCO list so that they can boost tourism, etc.

Where/when do you see an anxiety “from seeing that the creative achievement of Vietnam are not viewed as taking part as an equal in the global cultural field” coming from?

I’m not saying that this is incorrect. I just don’t have the knowledge of that topic.

I also get people in Vietnam asking me – when do you think Vietnamese folk music / songs / rock music / rap / classical music will be recognized by other countries or be able to compete in the international marketplace. They view my interest and knowledge about it as a hopeful sign. I try to be encouraging even though I’m not very sanguine about it. Part of it relates to what you discuss above — a tendency to want to essentialize one’s own cultural purity and not embrace things that have assimilated too far towards western cultural standards.

Reblogged this on Vietnam Travel & Trade Portal.