In 1282, upon seeing that crocodiles had reached the Lô River (i.e., the Red River), emperor Trần Nhân Tông ordered one of his officials, Nguyễn Thuyên to compose a document and throw it into the river in order to drive the crocodiles away.

The passage that records this event in the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư 大越史記全書 (Complete Book of the Historical Records of Đại Việt) states that the crocodiles “reached” or “arrived at” (chí 至) the Lô River.

That is a clear indication that crocodiles were not usually seen in that area. So where had these crocodiles come from?

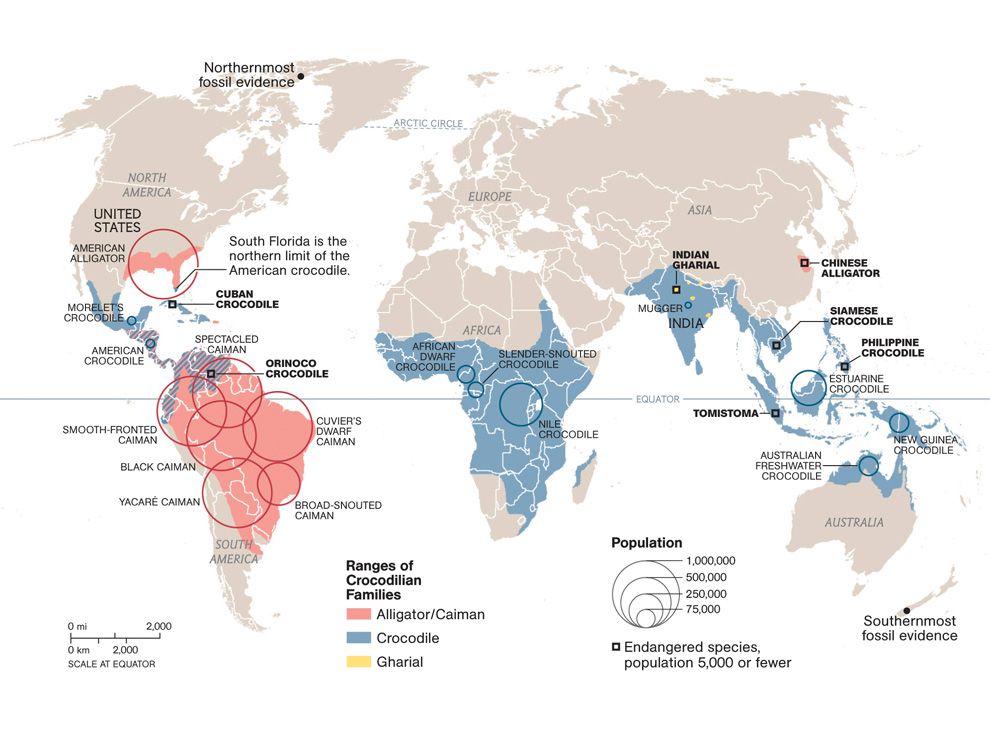

A few years ago, linguist Pittayawat Pittayaporn wrote a short article for the Cornell Southeast Asia Program bulletin about his research on Tai historical linguistics (see pages 12-17 of this document). In this article, Pittayawat talked about evidence that demonstrates that a branch of the Tai language family (Southwestern Tai – see the map above) emerged first in the area of Guangxi, and that the speakers of this language then spread towards the southwest as their language(s) continued to develop.

One word that demonstrates this movement is the word for “crocodile.” In southwestern Tai languages there are actually two words for “crocodile.” One comes from Chinese, and is used to refer to a “mythical snake-like water creature.” And one is of unknown origin, but it is used to refer to the actual living crocodiles that inhabit places like Thailand.

As Pittayawat explains:

“Although crocodilian species do exist in Thailand, the current Thai word for “crocodile, alligator” is a new word of uncertain origin, choorakhee จระเข้. While Chinese alligators (Alligator sinensis) were historically found only in the lakes and wasteland of the middle-lower Yangtze River Region, the Southeast Asian crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus, Crocodylus siamensis, and Tomistoma schelegelii) ranged the middle and lower parts of the Southeast Asian peninsula. This distribution leaves northern Southeast Asia and southern China crocodile-free.

So when proto-Tai speakers were living in the area of Guangxi, a place that did not have crocodiles, they must have heard about these creatures from the speakers of early Chinese, and the word entered their language. However, since these people had not actually seen a crocodile, they imagined it as some “mythical snake-like water creature.”

When, however, some of these people migrated toward the southwest into areas where Southeast Asian crocodiles live, they used a new word to refer to these creatures: choorakhee.

The Red River Delta, therefore, was in an area between two crocodile worlds, the Chinese and the Southeast Asian.

That is why the event of 1282 was recorded, because it was strange that crocodiles had arrived in the Red River Delta.

Where did those crocodiles come from? Probably from an area to the south as there is a passage in the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư for the year of 1363 in which crocodiles from the south are mentioned.

In that year certain improvements were made to a royal garden at the capital. This is what the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư records about that event:

“In winter, during the tenth lunar month, a pond was excavated in the Rear Palace Imperial Garden (Hậu Cung Ngự Uyển 後宫御苑). Stones were piled up in the middle of the pond to form a mountain. Each of the four sides opened onto canals that allowed for [the water] to flow. [On the mountain] above the pond were planted pine, bamboo and other trees, as well as strange flowers and odd plants. Precious birds and rare animals were also raised there.

“To the west of the pond a pair of cassia trees was planted and a palace for the pair of cassia trees was constructed. It was called the Enjoying Purity (or Peacefulness) Palace (Lạc Thanh Điện 樂清殿). The pond was called the Enjoying Purity Pond (Lạc Thanh Trì 樂清池).

“Another small pond was also made, and a Đông Hải person was ordered to bring salt water and fill [the pond] with it, and to raise sea creatures like hawksbill turtles, fish and sea turtles in the pond.

“A person from Hóa Châu was also ordered to bring a crocodile [or crocodiles] and release it in [the pond].

“There was also the Pure Fish Pond where “pure carp” [thanh phụ 清鮒] were released (Pronounced “phụ,” it is a goldfish [tức ngư 鯽魚]), and an official was stationed there to manage [the garden and ponds].”

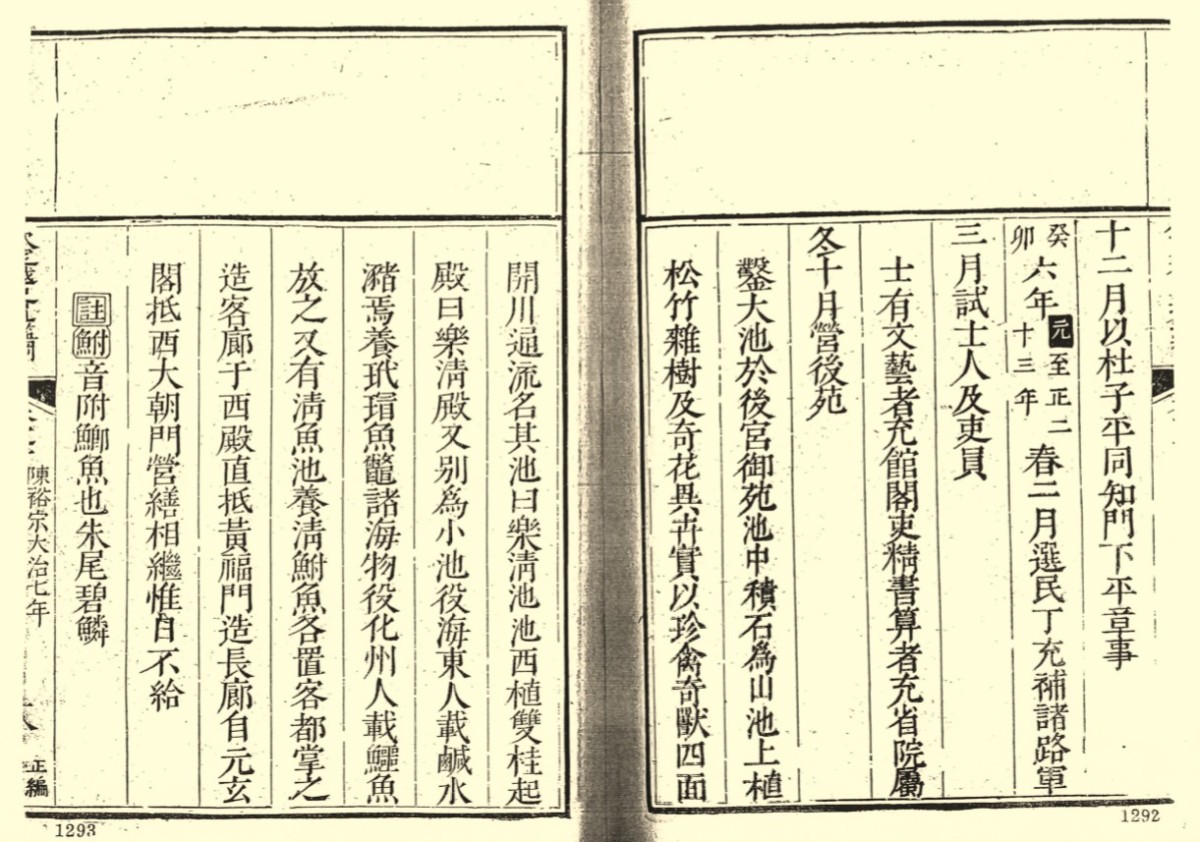

冬十月,鑿池於後宫御苑。池中積石為山,四面各開,川路通流。池上種松竹雜樹及奇花異卉,珍禽異獸又育於其中。池之西種雙桂,起雙桂殿,名其殿曰樂清殿,其池曰樂清池。又别為小池,令海東人載鹹水潴焉,以玳瑁魚鼈海物養於池中,又令化州人載鱷魚放之,又有清魚池放清鮒鮒音付,鯽魚也魚,並置客都掌之。

Mùa đông, tháng 10, đào [26a] hồ ở vườn ngự trong hậu cung.Trong hồ xếp đá làm núi, bốn mạch đều khai ngòi cho chảy thông nhau. Trên bờ hồ trồng thông, tre và các thứ hoa thơm cỏ lạ. Lại nuôi chim quý, thú lạ trong đó. Phía tây hồ trồng hai cây quế, dựng điện Song Quế [LMK: “dựng điện cho song quế” là đúng hơn.]. Lại [LMK: Trong văn bản không có chữ “lại.”] gọi tên điện là điện Lạc Thanh, tên hồ là hồ Lac Thanh. Lại đào một hồ nhỏ khác. Sai người hải Đông chở nước mặn chứa vào đó, đem các thứ hải vật như đồi mồi, cua, cá nuôi ở trong hồ [LMK: Trong văn bản không có chữ “cua.” Bản dịch của KĐVSTGCM có “đồi mồi, cá biển và loại ba ba” là đúng hơn.]. Lại sai người Hóa Châu chở cá sấu đến thả vào đó. Lại có hồ Thanh Ngư để thả cá thanh phụ [cá diếc] [LMK: Không phải là cá diếc.]. Đặt chức khách đô để trông coi.

Hóa Châu was somewhere around where Huế is today. At the time it was at the southern end of the Trần empire. This is what enabled them to demand that a crocodile be brought from that southern region to their capital.

These are the only references to crocodiles in the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư. What is more, both of these records present crocodiles as “alien” to the Red River Deta.

Not surprisingly, unlike Thailand where crocodiles feature in traditional tales and modern movies, these creatures are largely absent from the culture of the Vietnamese heartland in the Red River Delta.

So while these two records from the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư do not indicate that crocodiles were an important feature of Vietnamese life in the medieval period, they are nonetheless fascinating for what they show us about the political culture of the Trần Dynasty.

In using writing to drive away crocodiles, Nguyễn Thuyên engaged in a practice that Tang Dynasty official Han Yu had famously performed in the ninth century, and this demonstrates the adherence at the Trần Dynasty court to distinct East Asian intellectual currents and cultural practices.

And that the Trân had an “imperial garden” at their palace compound where they displayed “exotica” from across their realm, we can see a phenomenon where rulers tried to “display the world” that they controled that has parallels in many other medieval and early modern societies (and in colonial exhibitions), although I would check first to see if there had ever been something like this at the Chinese court.

These two crocodile stories can therefore tell us a great deal about the culture of Trần Dynasty rule, but as for crocodiles themselves, these brief records indicate that these animals did not play a significant role in the lives of people in the Red River Delta in the medieval period.

They were alien to the Red River Delta, and that made them exotic. And that’s also what made the Trần Dynasty’s pet crocodile so special.

This Post Has 3 Comments

Wow, that was some quick research. And that’s a wild poster. Have you seen the movie? The bigger take away from what you’ve written is that there may be many references in historical texts that might have had a symbolical, rhetorical or referential meaning but may have not have been literally true, but were useful for governance. (Nowadays the rulers might call them alternate facts?)

Pittayaporn says the Tai word for crocodile was clearly borrowed from Chinese, but Chamberlain argues what is exactly opposite to his point. These two opposite views lead to two drastically different hypotheses about the early distribution of the Tai.

Pittayaporn’s short article was published in 2009. Chamberlain probably did read Pittayaporn’s article but somehow he disagreed with his view on the etymology of the word crocodile. He is the first one who studies Tai zoology and published a number of papers on this topic. I think he has reason to disagree with Pittayaporn’s argument.