A friend recently scanned and sent me some pages from a new book by Vietnamese author Tạ Đức on bronze drums in Vietnam called The Origin and Development of the Đông Sơn Bronze Drums (Nguồn gốc và sự phát triển của trống đồng Đông Sơn).

This friend sent those pages to me because some of the ideas that I have posted about bronze drums on this blog are criticized in this book. In particular, I have argued that the cultural world of the people who used bronze drums for rituals and as symbols of power in the Red River delta in the first millennium BC is different from the cultural world of the people whom we today refer to as the Vietnamese (see, for instance, here, here and here).

The people we today refer to today as the Vietnamese created a culture (starting in the first millennium AD, and continuing through the centuries after that) through interactions with the people who lived to their north (the “Chinese”), and as they did so, they rejected the indigenous bronze drum cultural world.

This is a process that Catherine Churchman has clearly documented in a recent work on the Li and Lao peoples who inhabited the mountainous region between the Red and Pearl River deltas (The People between the Rivers: The Rise and Fall of a Bronze Drum Culture, 200–750 CE). In that work, Churchman clearly demonstrates how the Li and Lao gradually “Sinicized” their cultural and political lives, and in the course of this transformation, bronze drums ceased to be important to their world.

Tạ Đức wants to argue that bronze drums continued to be important for the Vietnamese. Let’s look at one of his arguments – his argument that bronze drums were still important during the Đinh period (968-980), that is, the earliest period of Vietnamese autonomy after a thousand years of being part of various Chinese empires.

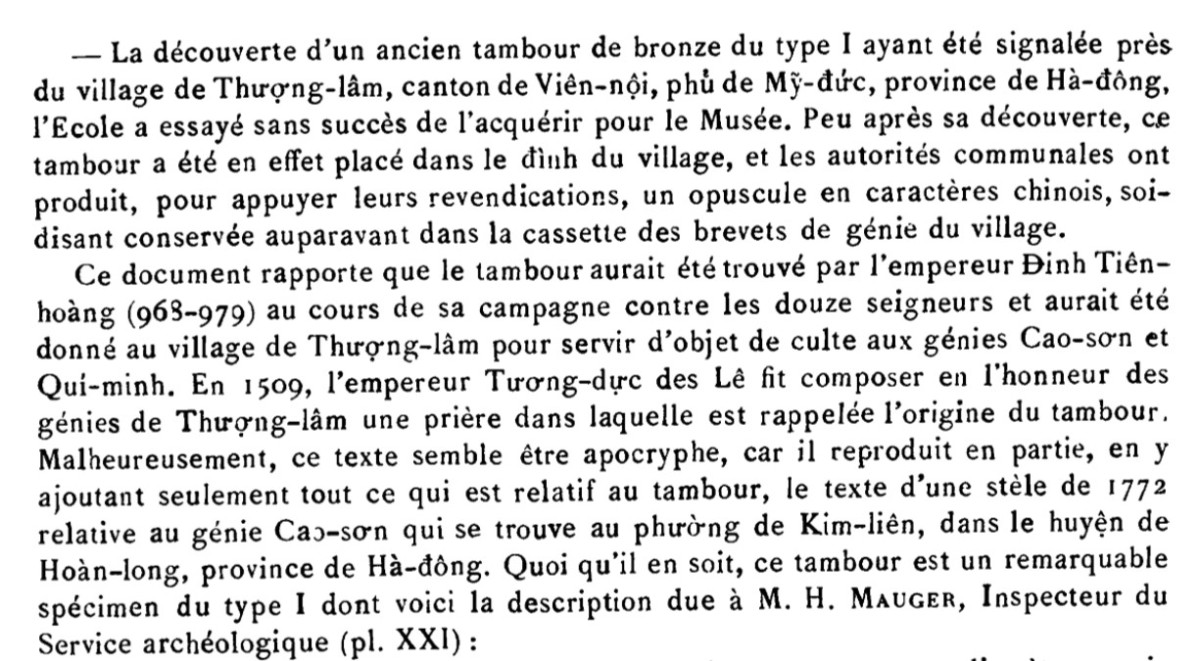

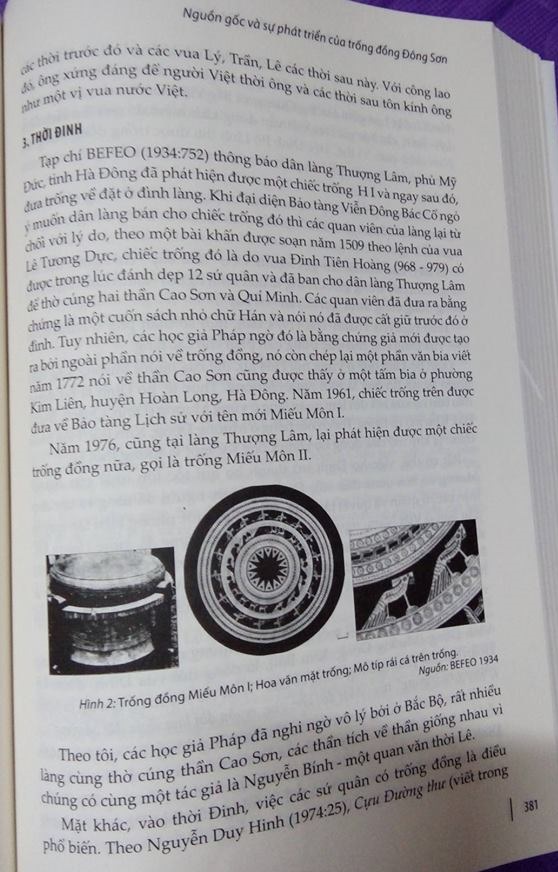

Tạ Đức notes that in the 1934 issue of the Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient there is a report about a bronze drum that was found in the village of Thượng Lâm (in what was then Hà Đông province). The people from the École Française wanted to place this bronze drum in a museum.

However, the village authorities refused to do this because they said that according to a prayer (bài khấn) that was ordered composed in 1509 by Emperor Lê Tương Dục, this bronze drum had been obtained by Emperor Đinh Tiên Hoàng in the tenth century while he was putting down 12 contenders for power at that time (12 sứ quân), and that he then gave this bronze drum to the village of Thượng Lâm to use while worshiping two spirits, Cao Sơn and Quí Minh.

The village authorities showed the people from the École Française this document, but the people from the École Française believed it to be fake, as its contents were exactly the same as the contents of a 1772 stone inscription from a nearby temple in Kim Liên (in what was then also Hà Đông province) dedicated to the spirit of Cao Sơn, the only difference being that the text in Thượng Lâm contained a passage about Đinh Tiên Hoàng and a bronze drum (which the scholars from the École Française suspected the village authorities in Thượng Lâm had added after the bronze drum had been found).

While the French scholars doubted the authenticity of this document, Tạ Đức thinks it is legitimate, and as proof of this he states that there are many places in northern Vietnam that worship Cao Sơn and that the texts about Cao Sơn at various temples are similar in that they were all written by Nguyễn Bính, a Lê Dynasty official.

(Theo tôi, các học giả Pháp đã nghi ngờ vô lý bởi ơ Bắc Bộ, rất nhiều làng cùng thờ cúng thần Cao Sơn, các thần tích về thần giống nhau vì chúng có cùng một tác giá là Nguyễn Bính – một quan văn thời Lê.)

It is true that (by the nineteenth century, an important detail that Tạ Đức does not mention) there were various temples in northern Vietnam that worshiped Cao Sơn, but it’s not clear to me how that supports his argument that bronze drums were important during the tenth century.

And as for Nguyễn Bính, he lived in the second half of the sixteenth century. If he is the one who wrote about the bronze drum that Đinh Tiên Hoàng supposedly obtained in the tenth century, how did he get that information?

After all, the 1772 inscription in Kim Liên that did not contain information about bronze drums was supposedly an inscription of a document that the Lê official, Lê Tung, composed in 1510, many decades before Nguyễn Bính wrote hagiographies of spirits. Lê Tung didn’t say anything about bronze drums. So how is it that Nguyễn Bính, a scholar who lived later, was able to learn about events that Lê Tung did not know about, and that occurred close to 600 years before his time?

In writing about the report in the Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient, there is an important detail that Tạ Đức doesn’t mention. That report makes the following comment about the bronze drum that was found in Thượng Lâm in the 1930s: “Shortly after its discovery, this drum was indeed placed in the communal hall of the village. . .” (Peu après sa découverte, ce tambour a été en effet placé dans le đình du village. . .).

So if this drum was placed in the communal hall AFTER it was “discovered,” where was it BEFORE it was “discovered”? If, as Tạ Đức argues, this bronze drum had been given to Thượng Lâm village by Đinh Tiên Hoàng in the tenth century for use in worshiping the two spirits, Cao Sơn and Quí Minh, shouldn’t it have been in the temple for those spirits already?

And shouldn’t there be some record from the more than 1,000 years between the tenth century and the 1930s that there was a bronze drum in this temple?

From the report in the Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient, it looks like this drum was found in the village (not in a temple), and then moved to the communal hall. So there is no evidence in this report to suggest that this bronze drum had anything to do with the worshiping of the spirits of Cao Sơn and Quí Minh, other than the fact that village authorities produced a document that contained 1) the text of an inscription from a nearby temple and 2) a passage about Đinh Tiên Hoàng obtaining a bronze drum in the tenth century and giving it to this village (a passage which French scholars at that time believed to be fake).

Tạ Đức goes on to argue that there is no reason to think that bronze drums were not used in Vietnam in the tenth century. As evidence of this he notes that Chinese sources from that time period note that there were people in the south of their empire called the “Lão” who had bronze drums, and Tạ Đức says that the Lão were the same as the Việt.

That is COMPLETELY FALSE. Chinese documents (and Vietnamese documents like the An Nam chí lược) make it EXTREMELY CLEAR that the Lão were not the same as the Việt, and that no one (neither Chinese nor Vietnamese) saw the Lão as the same as the Việt.

This is a topic that I’ve written about in the posts linked to above.

So there are problems with Tạ Đức’s logic and evidence, but the issue of the relationship between the spirit, Cao Sơn, and bronze drums is very interesting. And in investigating it, I’ve come to realize that it completely supports the view of Vietnamese history that I have been writing about for years.

And the information about the spirit, Cao Sơn, clearly demonstrates how Vietnamese society has CHANGED over time.

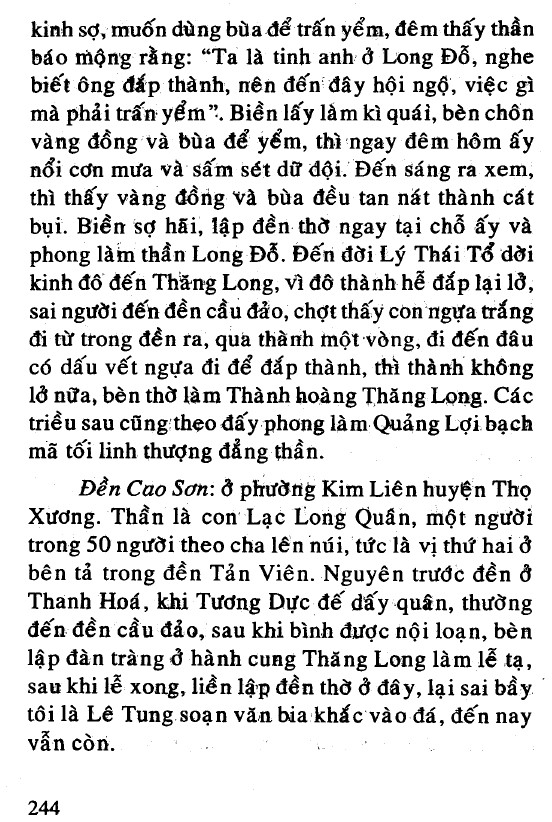

The 1772 inscription about Cao Sơn, which is attributed to a 1510 text by Lê Tung, says that the Lê emperor sent some officials to the south to put down unrest in 1509 (in an area near what later became Ninh Bình province).

At a village called Phụng Hóa, these men came across a temple that had a stone inside that was called the “High Mountain Great King” (Cao Sơn Đại Vương 高山大王). “Cao Sơn Đại Vương” is a 100% Sinitic title. The fact that this spirit was called by this name shows that a member of the Sinicized elite must have named this spirit.

However, the fact that the spirit was represented by a stone also suggests that there may have been an earlier, animist, cult at this sight.

This is something that occurred countless times in East Asia in the past. Local people would have a cult for a nature spirit, and then a member of the (Sinicized) elite would come along and “transform” the spirit into one that served the interests of the elite. The reason why they did this was to try to bring people under the authority of the government by getting them to believe in, and obey, spirits that the government approved of.

That said, in the early sixteenth century the Lê emperor went a step further. After his officials successfully put down the unrest in the Ninh Bình area, the emperor ordered that a temple for Cao Sơn Đại Vương be erected in Kim Liên, near the capital, so that this powerful spirit who had aided his officials in suppressing a rebellion could continue to be honored.

Moving ahead in time to the nineteenth century, texts like the Unified Gazetteer of Đại Nam (Đại Nam nhất thống chí) claimed that the spirits worshiped in the two Cao Sơn temples (in Phụng Hóa and Kim Liên) were actually children of the mythical figure, Lạc Long Quân. What is more, there were now other temples that also claimed to be dedicated to Cao Sơn, and where this spirit was identified as a son of Lạc Long Quân: one in Thượng Lâm (where the bronze drum was later found in the 1930s), and one in Sơn Tây (in the temple for the spirit of Mount Tản Viên).

What was going on here? I think it’s obvious.

In 1509 some Lê officials came across a temple in Ninh Bình that contained a nature spirit that had been “Sinicized” by some member of the local elite as the Cao Sơn Đại Vương (High Mountain Great King).

This was not long after the first account (the Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái – 1492) of the mythical figure, Lạc Long Quân, appeared. So it makes sense that this spirit at that time had nothing to do with Lạc Long Quân.

However, in the centuries that followed, knowledge about this mythical figure spread, and eventually stories emerged that linked Cao Sơn to Lạc Long Quân (or more specifically, to his sons).

That said, it would appear that those connections emerged after the inscription about Cao Sơn was made in Kim Liên in 1772, because if people believed at that time that Cao Sơn was a son of Lạc Long Quân, you would think that they would have made an inscription that mentioned that, rather than to simply reproduce a record from 1510 that did not mention anything about Lạc Long Quân.

The 1772 inscription also doesn’t say anything about bronze drums. This is because bronze drums had nothing to do with this religious cult at this time (or at any time before). Instead, it is only in the 1930s, when a bronze drum was found in Thượng Lâm – a village that had a temple dedicated to Cao Sơn, and which like the nearby Kim Liên temple, was now saying that this spirit was a son of Lạc Long Quân – that bronze drums became connected to this spirit.

But that connection only occurred because Europeans in the early twentieth century started to discover bronze drums in the region and draw people’s attention to these artifacts from the past.

Again, Tạ Đức wants to see continuity across time. He wants to imagine that there has been a single Vietnamese nation and a single Vietnamese culture that has endured through time.

However, the only way one can make this argument is by distorting historical evidence, because no society persists through time without undergoing massive changes, and the historical record documents those changes.

If, on the other hand, we look at historical evidence in its historical context, we can see those changes.

At some point in the distant past there was a nature spirit in the area of Ninh Bình. At some point before 1500, a member of the Sinicized elite transformed that spirit into Cao Sơn Đại Vương. Then in 1510 that spirit was brought from Ninh Bình to the capital. At some point after that (probably in the nineteenth century), ideas that first emerged in the fifteenth century about a mythical figure by the name of Lạc Long Quân came to be associated with this spirit. And in the 1930s, as the French were discovering evidence of the distant past through archaeology, a bronze drum came to be associated with this spirit at one of the temples dedicated to Cao Sơn.

From animism (the stone), to Sinicization (calling the stone “Cao Sơn Đại Vương”), to the creation of a local identity based on Sinitic concepts (the story of Kinh Dương Vương, Lạc Long Quân, etc. with all of its connections to Tang Dynasty era texts – see my article on this), to the embrace of modern nationalism with its claim that “nations” and their unique cultures endure through the centuries (the “discovery” of bronze drums as “Việt” culture). . . all of this can be seen in this story about the spirit Cao Sơn.

When one looks at the past through a nationalist lens, as Tạ Đức does, then one can’t see these changes, as everything that one sees must be interpreted as a sign of the continued existence of the nation and of an unchanging national culture.

When, however, one looks at the past from an historical perspective, all of these changes become obvious, and they are fascinating to see and think about.

This Post Has 9 Comments

Interesting! However, I think you shouldn’t outright call him a nationalist, because your arguments are quite enough, especially when juxtaposing them with his criticism of you in his brief. By the way, I don’t get it, why the continuity is that important to some people. I’m personally fine, whether my (current) traditional culture has persisted for a long long time or not.

I TOTALLY agree with you, and just reworded those passages.

Yea, one problem is that in the Vietnamese world, the term “nationalist” tends to be seen as referring to some “crazy” people who march down the street with their hands in the air demanding something. . . Whereas in the historical profession where I work, the term “nationalist” refers to someone who uses the concept of the nation as the main tool for examining the past.

However, what tons of scholarship has shown by now is that “nations” cannot be seen through time. They are not something that have always existed, or have not always existed in their current condition. So when you look for evidence of a current nation and its culture 1,000 years ago, you end up distorting the past, because societies/cultures in the past were very different from what they are now.

I also don’t understand why people find continuity so important. One of the first things that got me interested in history was when I was a kid I saw some pictures of my town that were taken in the early 20th century, and what got me so excited was to see how DIFFERENT my town looked. Yea, there was enough that was the same so that I could still recognize that it was my town, but so many of the details were different, and I remember thinking how cool that was to see.

“The past is a foreign country.” That’s what’s so interesting about it.

“Nationalist”, in Vietnamese political context, has another meanings in the 1940-1970s: those who are anti-communists. As a “student of history”, I learn new things every time I read your blog. Thank you Sir.

Vietnamese everywhere have drummed into their minds the idea of 4000 năm văn hiến – that they are direct descendants of the same people who lived in the Red River delta back then. It’s difficult to discard an idea that is central to one’s identity. I think Americans (with only mấy trăm năm văn hiến) experience the same kind of dissonance when discovering that their forefathers who were so eloquent on the subject of liberty owned slaves, or that the pursuit of happiness entailed eradicating native people. As you entry demonstrates, much of the time what is recorded and passed down is the interpretation of people in power who have their own political ends in mind.

The term “trống đồng/bronze drum” wasnot something unknown for Vietnamese people until 19th century.

In that book, page 91 a.

——–

Ngày 15, vua đích thân dẫn trăm quan bái yết Sơ lăng và ra lệnh chỉ cho quan coi lăng ở Lam Sơn rằng:

“Mọi việc ở đền thờ cần phải thành kính, tinh khiết như ngả cây, chặt che, kiếm củi… tế tẩm miếu dùng 4 trâu, đánh trống đồng, [91b] quân lính reo hò hưởng ứng. Về nhạc, võ thì múa điệu “Bình Ngô phá trận”, văn thì múa điệu “Chư hầu lai triều”

——-

I will translate for people cannot read Vietnamese context but I am really sorry about my bad English.

——–

“In the 15th February 1456, the Le king (Le Nhan Tong) and his mandarin went to the royal temple (I donot know how to translate correctly that term) and gave the mandate:

– In temple, everyone need honor, respect like cut down the tree, … when sacrificing use 4 buffaloes, beat the bronze drum, [change to page 91b] solider roar and yell. As for the music, when shows kungfu, dance the “Bình Ngô phá trận”, when shows literature, dance the “Chư hầu lại triều”

”

——–

So the bronze drum actually is something appears in royal custom level in Le dynasty and it wasnot something unknown for Vietnamese people until 19th century.

Last time, you translate “lại triều” to “pay tribute to the court” can be “go/back to the court”. And the ideas you gave before is only a guess.

I can agree with you that the area of what is today Vietnam was a multi-ethnic region that a Sinicized elite gradually conquered and extended their control over. However the thing so-called Sinicized elite isnot homogeneous too. It is highly likely that the elite using Chinese writing system as well as borrowing Chinese administration system to control the whole land. However, even the Sinicized elite has different origin. Some from Tang-Chinese, some from southern “barbarian” Chinese, some from “local barbarian”. So the differences between modern VNese and modern Chinese are has some origins. First origin was from the “local custom” of local area. Second origin (may be more importance) was from the elite who controlled the country/area at that time and make their custom famous on whole population they controlled.

The Vietnamese culture even now is not homogeneous even in northern part of VN. So we can not imagine or conclude based on this kind of homogeneous. There is growing body of evidence that some customs was quite importance at some period but disappear latter.

The bronze drum can be importance for the Latter Le court as it appear in Dai Viet Su Ky toan thu at this period but it can disappear in Mac court and Le-Trinh court latter.

The Dinh and Early Le court has Hoa Lu – capital. So, it is possible that bronze drum is importance at that period. The sprite of Bronze Drum in Đồng Cổ was wrote in Ly period can be a hint.

Thanks for the comments!!

I don’t think I ever said “the term” for bronze drum was not known before the 20th century. What I’ve been trying to say is that bronze drums were not central to Vietnamese life in premodern times (= thoi phong kien).

We have 2 places in Vietnamese sources that mention bronze drums. There is the one from the Ly were a bronze drum is brought back after a campaign against the Cham and placed in a temple, and the one here from the first half of the 15th century, where it appears that a local temple in Lam Son had bronze drums that people hit (when a Sinitic ritual was performed).

In both of these cases, the drums were from “the south,” or what I would call “the periphery” of the Viet world. In both of these cases, I would also argue, we can not see any sign of possible ritual continuity or meaning from the time of the Dong Son period.

What I mean by that can be seen in the picture that I have posted a few times of two men wearing traditional robes with a bronze drum sitting on a table. Those two men were Muong, that is, people from the periphery of the dominant Vietnamese world. Yes, a bronze drum is there, an “object” is there, but there is no sign from that picture that the meaning of that drum for those two men, or what they did with it, was in anyway the same as the meaning or use of bronze drums during the Dong Son period. What is more, we can also see that those two men, had been Sinicized (or East Asian-icized, if we want to avoid any reference to things “Chinese”) to some degree.

“Chư hầu lại triều” is a very specific term. It can be found first in the Shijing (Classic of Poetry) and then many times after that.

前來朝覲。詩經.小雅.采菽:「諸侯來朝,不能錫命。」

Yes, “pay tribute to” in the sense of “give gifts to” is not an accurate translation of “lại triều,” but “pay tribute to” in the sense of “to honor” is closer to the meaning. A better translation would be “to come to the court and have an audience with the emperor.” Who does that? The chư hầu, the “vassal lords.”

From an earlier passage in the Dai Viet su ky toan thu, we can see that the “Bình Ngô phá trận” dance (“victorious battle in pacifying the Ngo) was created by the emperor, and my guess would be that the “vassals come to have an audience with the emperor” dance was also created at the court. The bronze drums that were hit at this one occasion that we have a record for, however, were in Lam Son, again, on the periphery of the Vietnamese world at that time.

I totally agree with you that Vietnam is multi-ethnic and multi-cultural and multi-everything. However, like everywhere in the world, the dominant culture is created by one group, and that one group makes the decision of what is part of its culture and what isn’t.

In the 20th century, under the influence of modern nationalism, it was decided that the bronze drums are symbols of Vietnamese culture. Did Muong people make this decision? No. Did people in Lam Son make this decision? No. It was people in places like Hanoi whose ancestors had not seen a bronze drum in 2,000+ years. Why did they chose that as a symbol of Vietnam? Because it showed that there was a sophisticated society in the region in the distant past, and one of the main goals of nationalism is to try to create a glorious and ancient ancestry for the modern nation (and that often requires that one distort the past in order to do so).

However, what the 2 cases of bronze drums in the DVSKTT show is that the dominant group throughout the premodern period did not value or make use of bronze drums. Le Loi was from the periphery. The elite in Hanoi were culturally different, just as the elite in Hanoi today are culturally different from people in the distant countryside. In the ritual mentioned here, we can see a process of Hanoi’s Sinitic culture getting extended to the periphery. What started to happen in the 20th century is that the people in Hanoi started to take an object from the periphery of space and time (the bronze drum) and say “oh, that’s ours. That’s always been ours.” Hmmmmm. . . Ok, but for at least the past 1,000 years you haven’t had anything to do with that. . .

That’s the point I have been trying to make. And thanks again for your comments!!!

[Tạ Đức is looking at the past through a nationalist lens. What this means is that he thinks that the nation and its culture have always existed in a recognizable form, and he is looking for evidence of the nation and of an unchanging national culture in the past. ]

[Tạ Đức wants to see continuity across time. He wants to imagine that there has been a single Vietnamese nation and a single Vietnamese culture that has endured through time.However, the only way one can make this argument is by distorting historical evidence] . Under the sun , everywhere , people revisit , rewrite history , re-interperet past history with a modern lens .

Is there a catchphrase within historians ‘ community to summarize those preposterous endeavours ?

In the case of French and Vietnamese people , instead of getting a glorious past , they passionately appropriate themselves “false induced memories ” , an odd narrative of centuries of enslavement combined with a fiction of keeping their spirit of resistance along with an unadulterated culture . Maybe we should call that the ” Gaulois – vietnamese syndrome “

In 1800, it still had bronze drum in Red river delta. We found Canh Thinh bronze drum.

http://baotanglichsu.vn/vi/Articles/1002/28214/trong-djong-canh-thinh.html

It is used for religious.

In 1800, it still had bronze drum in Red river delta for religious reasons.

http://baotanglichsu.vn/vi/Articles/1002/28214/trong-djong-canh-thinh.html