Let’s now look at the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” to see to what extent we can find evidence that it was created by “representatives of the people” who had decided together to break away from an empire and to enter “a pre-existing international order” as “equal to other, similar states” by seeking the approval of the other states in that international order.

Let’s begin by looking at who the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” talks about and try to see to what extent it represents the expression of “representatives of the people.”

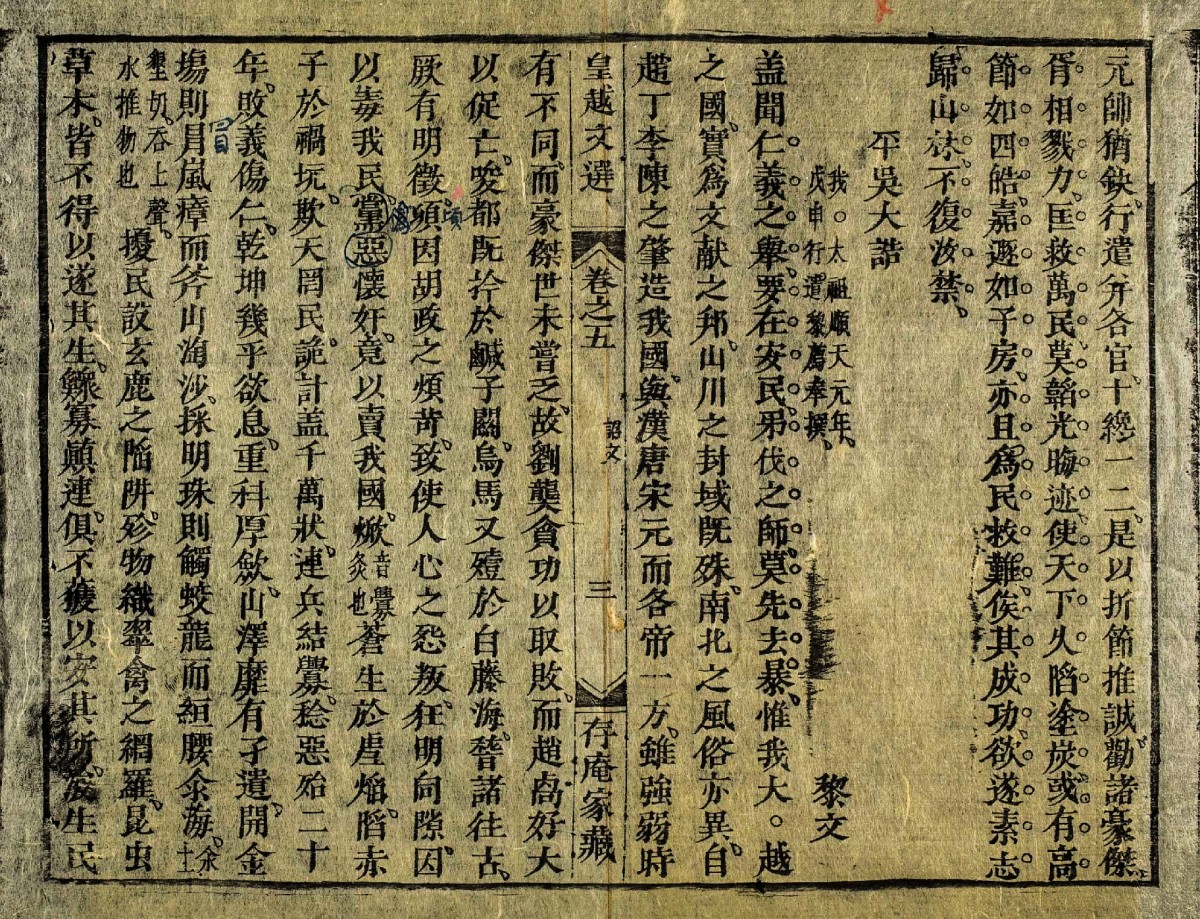

The “Bình Ngô đại cáo” starts out by talking about the kingdom of Đại Việt and makes the case that this kingdom has long existed as a separate kingdom and that no one has been able to change that reality.

From the opening passages it certainly looks like this will be a document about “the people,” but let’s look at what follows. The document goes on to say that,

“Recently, the tyranny of the Hồ regime incited hatred and rebelliousness in people’s hearts. The mad Ming took advantage of this opening and poisoned our people. Evil factions harbored treachery and sold our kingdom.”

[頃因胡政之煩苛,致使人心之怨叛。狂明伺隙,因以毒我民。惡黨懷奸,竟以賣我國。

Khoảnh nhân Hồ chính chi phiền hà, trí sử nhân tâm chi oán bạn. Cuồng Minh tứ khích, nhân dĩ độc ngã dân; ác đảng hoài gian, cánh dĩ mãi ngã quốc.]

So yes, here there is also a sense of an “us,” as this passage mentions “our people” and “our kingdom.” However, there is a definite difference between saying “our people” and saying “we.” “Our people,” I would argue, is more of an elitist and paternalistic expression which represents a pre-democratic worldview, which is what we should expect to find in a document like the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” given that Đại Việt had long been an absolute monarchy.

It literally means “my people” (我民 ngã dân) and is thus similar to a European absolute monarch’s view of “my subjects.”

“We,” on the other hand, is an expression and concept that reflects a more democratic worldview, which again is something that we should expect to see in a document like the American Declaration of Independence (although of course that “democratic worldview” at that time did not include slaves, women or even men who did not own land).

Nonetheless, there is a premodern, elite sense of “we-ness” expressed in this document that is typical of what existed in kingdoms controlled by absolute monarchies in many parts of the world at that time.

Who else is in this document? The document mentions the “mad Ming” (狂明 cuồng Minh), but it also mentions “evil factions” (惡黨 ác đảng).

We know from sources like the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư and the letters written by Nguyễn Trãi that members of those “evil factions” did not just “sell our country” and then go home. Instead, there were members of those “evil factions” who collaborated with the Ming throughout the entire period.

The document then goes on to talk about all of the terrible things that happened over the next 20 years. Who were the people who did all of those terrible things? Was it just the “mad Ming”? Or did members of those “evil factions” participate too?

The document is not clear as there is no clear subject for the actions that it describes. One would assume that collaborators played a role, but the document does not explicitly say that.

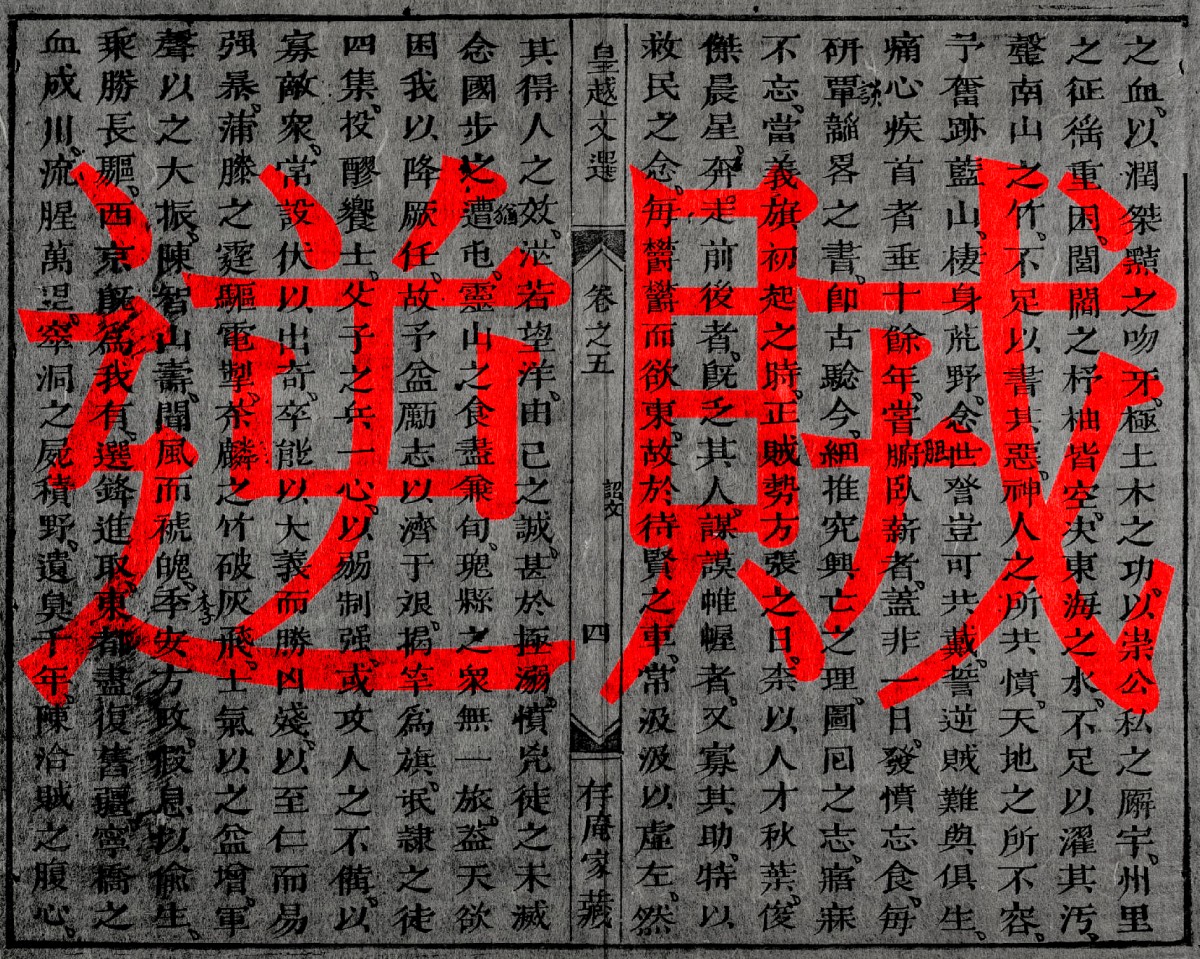

The term “Ming” is only mentioned that one time in reference to the “mad Ming.” In the rest of the document we find the titles and given names of the Chinese officers that Lê Lợi fought against, like Liu Sheng and Wang Tong. And the term “rebel” appears five times (賊 tặc).

That term appears in a passage that mentions that Lê Lợi vowed to not live together with “traitorous rebels” (逆賊 nghịch tặc).

When referring to people who invaded “Vietnam” from “China,” the terms that were usually used were terms like “northern rebels” (北賊 bắc tặc) or “northern bandits” (北寇 bắc khấu) or simply “rebels” (賊 tặc).

“Traitorous rebels” (逆賊 nghịch tặc) is a term that was usually used for internal enemies, like “traitorous factions” (逆黨 nghịch đảng) or “traitorous outlaws” (逆匪 nghịch phỉ). However, theoretically it could have been used here to refer to the Ming army which was “betraying” or “going against” the rightful way that things should be.

This is the only time that the expression “traitorous rebel” is used. However, the term “rebel” (賊 tặc) on its own is used four more times. The document mentions that Lê Lợi began his uprising “right when the strength of the rebels was at its peak” (正賊勢方張之日 Chính tặc thế phương trương chi nhật). It mentions two rebels that were killed, Trần Hiệp (陳洽) and Lý Lượng (李亮). Trần Hiệp was Chiense, and I’m assuming that Lý Lượng was as well. Finally, there is a reference to “rebel leaders” (賊首 tặc thủ) getting captured, and one reference to “bandits” (寇 khấu).

So while there is no consistent term that is used to refer to “the enemy,” and while we know that members of those “evil factions” collaborated with the Ming, the document itself is clearly a narrative of a fight against the occupying Ming army, as it makes frequent reference to the Ming Dynasty officers that Lê Lợi and his soldiers fought against, such as Liu Sheng, Huang Fu and Wang Tong.

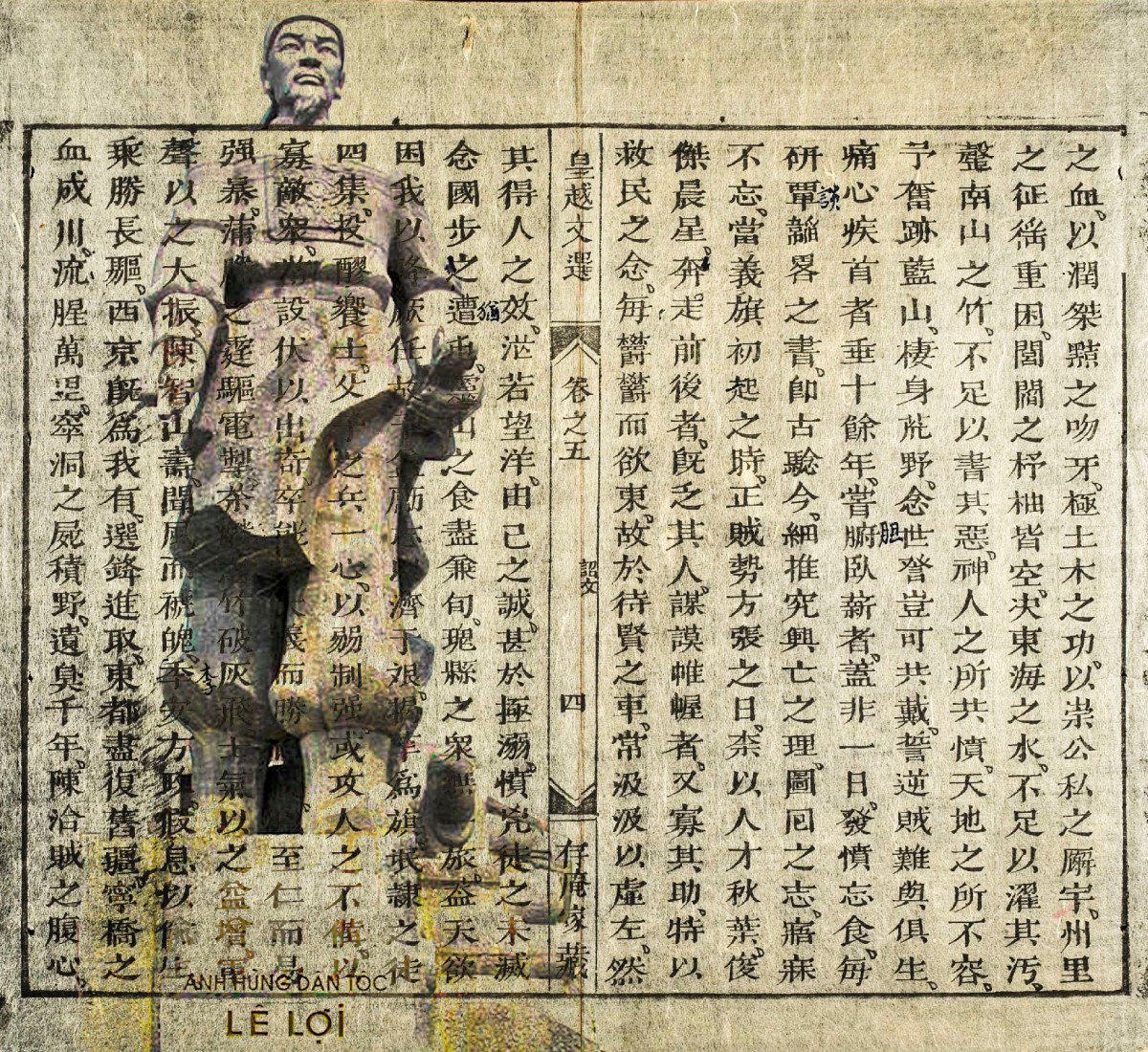

Who fought against the Ming army? This is where the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” gets interesting, because the portion of the text which narrates the war against the Ming is told from a first-person perspective. That is, the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” does not say that “we” fought the Ming, but instead, it says that “I” (予 dư) fought the Ming. Who is “I”? It is Lê Lợi.

“I rose from Lam Sơn” (予奮跡藍山 Dư phấn tích Lam Sơn)

“I therefore tried to cultivate a will as would overcome all hardship” (故予益厲志以濟於艱 Cố dư ích lệ chí dĩ tế vu nan)

“I had, first of all, the best of our troops posted at various strategic positions” (予前既選兵塞險,以摧其鋒 Dư tiền ký tuyển binh tái hiểm dĩ tồi kỳ phong)

“Furthermore, I also placed some regiments in control of the roads” (予後再調兵截路 Dư hậu tái điều binh tiệt lộ)

“I myself chose to act in accordance with the merciful spirit of the Thearch on High [Thượng Đế]” (予亦體上帝好生之心 dư diệc thể thượng đế hiếu sinh chi tâm)

“I myself had no higher concern than the security of the troops” (予以全軍為上 )

The above quotes follow, with a few modifications, follow Trương Bửu Lâm’s translation (attached below). I have only cited the sentences where the pronoun “I” (予 dư) actually appears in the text. However, a basic rule of classical Chinese is that the subject remains the same unless a new subject is introduced.

Therefore, even though the pronoun “I” (予 dư) only appears six times, the subject of parts of the intervening passages is still understood to be “I.”

That is why Trương Bửu Lâm used the pronoun “I” a total of (if I didn’t count incorrectly) 19 times in his translation of the portion of the text that deals with the fight against the Ming.

So the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” was clearly not created by a group of “representatives of the people.” It does mention that the kingdom of Đại Việt has a right to exist, and it mentions “our/my people/subjects.” However, the majority of the text talks about what “I” (Lê Lợi) did.

Before we draw any conclusions about that, let’s first consider to what extent the “Bình Ngô đại cáo” expresses a decision to break away from an empire and to enter “a pre-existing international order” as “equal to other, similar states” by seeking the approval of the other states in that international order.

Bình Ngô đại cáo English translation

This Post Has 6 Comments

Did Lê Lợi intend to break away from the empire? Not really!

It was rather surprising to me to read his admission in “Lam Sơn Thực Lục”, that his uprising was all ,,, shall we say … accidental, or more accurately, reluctant!

I am enclosing herewith his admission in the end of the book Lam Sơn Thực Lục, volume 3:

—————————————————————————————–

Trong khi muôn việc có rỗi, Nhà-vua thường cùng các quan bàn-luận về duyên-cớ thịnh suy, được, mất từ xưa đến nay. Cùng là giặc Ngô sở dĩ thua, Nhà-vua sở dĩ thắng là vì cớ làm sao?

Các quan đều nói rằng:

– Người Ngô hình-phạt tàn-ác, chính-lệnh ngổ-ngược, mất hết cả lòng dân. Nhà-vua làm trái lại đạo của chúng, lấy nhân mà thay bạo, lấy trị mà thay loạn, vì thế cho nên thành công được mau-chóng là thế!

Nhà-vua phán rằng:

– Lời các thầy nói, tuy là đúng lẽ, nhưng cũng còn có điều chưa biết. Trẫm trước gặp lúc loạn-ly, nương mình ở Lam-sơn, vốn cũng mong giữ toàn được tính-mệnh mà thôi! Ban đầu cũng không có lòng muốn lấy thiên-hạ. Đến khi quân giặc càng ngày càng tàn-ác, dân không sao sống nổi! Bao nhiêu người trí-thức, đều bị chúng hãm-hại. Trẫm đã chịu khánh-kiệt cả gia-tài để thờ-phụng chúng! Vậy mà chúng vẫn đem lòng muốn hại Trẫm, không chịu buông tha! Việc khởi nghĩa, thực cũng là bất-đắc-dĩ mà Trẫm phải làm! Trong lúc ấy, Trẫm thân trọ quê người, vợ, con, thân-thích, đều tán-lạc hết! Cơm không đủ hai bữa! Áo không phân Đông, Hè! Lần gặp nạn ở núi Chí-linh, quân thua, lương hết! Trời kia bắt lòng ta phải khổ, trí ta phải mệt, đến thế là cùng! … Trẫm thường dụ bảo các tướng-sĩ rằng: “Hoạn-nạn mới gây nổi nước! Lo-phiền mới đúc nên tài! Cái khốn-khổ ngày nay là trời thử ta đó mà thôi! Các thầy nên giữ vững lòng xưa, cẩn-thận, chớ vì thế mà chán-nản”. Vậy mà tướng-sĩ cũng dần dần lẩn trốn! Theo Trẫm trong cơn hoạn-nạn, mười người không được lấy một, hai! Còn bỏ Trẫm mà đi, thì đại-loại là phường ấy cả! Kể như lúc ấy, nào ngờ lại có ngày nay! May mà Trời chán đứa giặc! Phàm lúc giặc làm cho Trẫm cùn, trí Trẫm lại càng thêm rộng! Phàm cách giặc làm cho Trẫm khổ, lòng Trẫm lại càng thêm bền. Trước kia quân-lính đói thiếu, giờ lại nhờ lương của giặc mà số trừ-súc của ta càng sẵn! Trước kia quân-lính lẩn-trốn, giờ lại mượn binh của giặc, mà trở giáo để chúng đánh nhau! Giặc có bao nhiêu mác, mộc, cung, tên, ấy là giúp cho ta dùng làm chiến-cụ! Giặc có bao nhiêu bạc, vàng, của báu, ấy là cung cho ta lấy làm quân-lương! Cái mà chúng muốn dùng để hại ta, lại trở lại làm hại chúng! Cái mà chúng muốn dùng để đánh ta, lại trở lại để đánh chúng! Chẳng những thế mà thôi: Kìa như nước Ai-lao, với Trẫm là nước láng-giềng, trước vẫn cùng nhau giao-hảo. Khi Trẫm bị giặc vây khốn, đem quân sang nương-nhờ. Nghĩ rằng môi hở, răng lạnh, thế nào chúng cũng chứa ta! Nào ngờ quân dạ thú, lòng lang, thấy ta bị tai-vạ, thì lấy làm vua-sướng! Rồi thông tin với giặc, ngầm chứa mưu gian, muốn để bắt vợ con của quân ta! Vậy mà ta tìm cách để đối-phó với chúng, thật là thong thả có thừa! Nó vốn trông vào quân giặc để đánh-úp ta! Ta cũng nhân vào thế nó, để đánh lui giặc! Nó vốn lấy khách đãi ta! Ta cũng lấy khách mà xử nó! Phàm ý nó muốn làm gì, ta tất biết trước! Vẻ nó muốn động đâu, ta tất chẹn trước! Cho nên có thể lấy đất đai của nó, làm nơi chứa quân cho ta; lấy hiểm-trở của nó, làm nơi lừa giặc của ta! Binh-pháp dạy: “Lấy khách làm chủ, lấy chủ làm khách”, có lẽ là như thế chăng? Thế nhưng Trẫm đối-đãi với ai cũng hết lòng thành-thực. Thà người phụ ta, ta chớ phụ người! Phàm kẻ bất bình vì một việc nhỏ, mà đem lòng kia khác, Trẫm thường tha thứ, dong cho có lối đổi lỗi. Tuy nhiều khi chúng trở mặt làm thù ngay, nhưng Trẫm thường tin-dùng như gan-dạ! Biết đổi lỗi thì thôi, không bới lông tìm vết làm gì! Ấy cũng là bởi Trẫm trải nhiều lo nghĩ, nếm đủ gian-nan, cho nên biết nén lòng nhịn tức, không lấy việc nhỏ mà hại nghĩa lớn, không lấy ý gần mà nhãng mưu xa. Trong khoảng vua, tôi, lấy nghĩa cả mà xử với nhau, thân như ruột thịt, có gì mà phải ngờ-vực. Thế cho nên có thể được lòng người, mà ai ai cũng vui lòng tin theo. Tuy vậy, trong khi hoạn-nạn, mười chết, một sống, kể lâm vào nguy-hiểm là thường! Ngày nay may được thành công, là do Hoàng-Thiên giúp-đỡ, mà Tổ Tiên Trẫm chứa nhân tích đức đã lâu, cũng ngấm-ngầm phù-hộ, cho nên mới được thế. Đời sau kẻ làm con-cháu Trẫm, hưởng cái giàu-sang ấy, thì phải nghĩ đến Tổ, Tông Trẫm tích-lũy nhân-đức đã bao nhiêu là ngày, tháng; cùng công-phu Trẫm khai sáng cơ-nghiệp bao nhiêu là khó khăn! Mặc những gấm-vóc rực-rỡ, thì phải nghĩ đến Trẫm ngày xưa áo, quần lam-lũ, không kể Đông, Hè! Hưởng những cổ-bàn ngon-lành, thì phải nghĩ đến Trẫm ngày xưa hàng tháng thiếu lương, chịu đói nhịn khát! Thấy đền-đài lộng-lẫy, thì phải nghĩ đến Trẫm ngày xưa ăn mưa, nằm cát, trốn lủi núi rừng! Thấy cung-tần đông, đẹp, thì phải nghĩ đến Trẫm ngày xưa thất-thểu quê người, vợ con tan-tác! Nên nhớ rằng Mệnh Trời nào chắc được không thường, tất phải suy-tính nỗi khó khi mưu-toan việc dễ. Nghiệp lớn khó gây mà dễ hỏng, tất phải cẩn-thận lúc đầu mà lo tính về sau. Phải đề-phòng đầu mối họa-loạn, có khi vì yên-ổn mà gây nên. Phải đón-ngăn ý-nghĩ kiêu-xa, có khi vì sung-sướng mà sinh sự! Có như thế thì họa là mới giữ-gìn được. Nên Trẫm nghĩ làm ra bộ sách này, thực là rất trông-mong cho con-cháu đời sau!

———————————————————————————————–

In particular, here is what he said:

“Trẫm trước gặp lúc loạn-ly, nương mình ở Lam-sơn, vốn cũng mong giữ toàn được tính-mệnh mà thôi! Ban đầu cũng không có lòng muốn lấy thiên-hạ. Đến khi quân giặc càng ngày càng tàn-ác, dân không sao sống nổi! Bao nhiêu người trí-thức, đều bị chúng hãm-hại. Trẫm đã chịu khánh-kiệt cả gia-tài để thờ-phụng chúng! Vậy mà chúng vẫn đem lòng muốn hại Trẫm, không chịu buông tha! Việc khởi nghĩa, thực cũng là bất-đắc-dĩ mà Trẫm phải làm ”

“Previously I was hiding in Lam Sơn during the tumultous time, trying only to save my life. In the beginning I did not want to take the country. Then the enemy became more ruthless, the people could not survive… I spent my whole family fortune to worship them(the enemy), yet they still wanted to harm me. The uprising was in fact something I had to do unwillingly” (pardon my rough translation).

And all this is at the time of the writing of Bình Ngô Đại Cáo. Bình Ngô Đại Cáo was included in the Lam Sơn Thực Lục as part of it. One could say Lam Sơn Thực Lục is a much more detailed version of BNDC where the author wanted the readers to know about his struggles and victories against the Chinese (yes, the Ngô).

(to be continued…)

One thing that is really important to try to understand is “humility” in writings in classical Chinese. Scholars in the past used a lot of humble expressions: “This writing is just some random notes that I jotted down without really considering what I was doing.” That might be literally what someone wrote but it’s not what the person actually thought. Instead, he thought something closer to the opposite: “I worked my ass off to compile this information here and to explain it, and I KNOW that I am right! So don’t you dare try to question me!!” (I’m exaggerating, but I think you get the point).

Also, the Lam Son thuc luc is total propaganda. If we read it as total propaganda, then there is a lot there that is interesting. But if we try to read it as accurate records about the past. . . then we will get ourselves into trouble.

Dear, In this comment I will write about the way Vietnamese people understand the BNĐC and discuss that is right or wrong way.

First, In our minds, BNĐC is never confirmed officially as a Declaration (you can view some books over “history of Vietnamese Literature”, authors always introduce BNĐC as “written by Nguyen Trai in order to annouce Le Loi’s victory and the way he won the throne” (Duong Quang Ham). If we say (example, in the school text book) BNĐC was a declaration, it will be only a funny comparision to the 1945 Declaration by Ho Chi Minh (which is a way to support the compatriotism).

Second, if we (Vietnamese) do not think about BNĐC as a declaration, how will we understand it? Yes, basically, we start to read it from it’s “genre” and “type” (thể loại và loại hình). A type of a text is defined by its function and A genre of a text is defined by its form. So Type and Genre are different concepts. But in Chinese Classical Literature, “genre” and “type” could have a same name and could be relative. So if a text has a type defined, it MUST belong to a correlative genre. “Đại Cáo” is a type of text, and also a genre of Literature. It was written in a “Đại Cáo” form, and had the “Đại Cáo” function. “Đại Cáo”, originally, was a name of 35th chapter in “Chu Thư” part of “Kinh Thư” book, in which The Duke of Zhou announce his throne to “Thiên Hạ”. Then Đại Cáo was used as a literature genre to officially announce the achievement and a role of a new King. Cáo is also confirmed as a type – along with Hịch, Chiếu, Biểu… – with its own form as we read (example it had an eloquent writting style and an own “niêm luật” – the phoneme connection between sentences …). “Declaration” is a function of text – not a type, a genre. BNĐC could not be a declaration in that meaning, because it didn’t have international background, and simply, it had its own type – genre which did not need “international announcement” function.

Third, after having read BNĐC in its type-genre, we easily define its context: the Spokemans was of course the King and the listeners were “Thiên hạ”. “Thiên hạ” is a complicated subject. First, importantly, it included the court officials. Second, it were all people and non-people (deities, gods…) in Kingdom. BNĐC had two important functions: give a new information of throne-situation (“Xã tắc dĩ chi điện an”) and discuss about rational basis of morality of the New King (“Nhân nghĩa chi cử, yếu tại an dân”). In the other words, it introduced new King and explained that the New King met the Confucian Morality demands.

Fourth, “people” and “traitorous rebels” were not a concrete group of people. These concepts must be understood in morality aspect. “People” were one of subjects of Confucian politics morality. So you are a bad or a good King depends on how you attain peace for your “people” (an dân). “People” never mean the people who the King represent (so King Le Loi did not say “we”). And Rebels were who against the peace of “People”. (Following comment of Winston Phan, Lam Son Thuc Luc said: “Then the enemy/rebel became more ruthless, the people could not survive…”). Rebels (tặc – 賊) was original meaning “damage, hurt” (Thiều Chửu in his famous sino-viet dictionary added: who damage the “People” are 賊) So Ming were traitorous Rebels!

So, my conclusions are:

– Modern Vietnamese people in their minds and in their education understand seriously the BNĐC with its Genre-Type.

– That way of understanding is not wrong.

– BNĐC is an announcement more than a declaration. BNĐC (and Lam Son Thuc Luc) is simply an explanation about why and how Le Loi won the Throne. It emphasized the Confucian morality basis of the new King, in which, wiping out the rebels (Ming) was one of evidence that Le Loi had true reasons to be a new Kingdom leader.

Also, one more quick comment about your opening comment about how “the Vietnamese people” think and suggesting that I look at Duong Quang Ham. One thing that we will see when I write later about “nam” and “bắc” is that ideas have changed over the course of the 20th century, and “educated Vietnamese” (the people who write and publish) have not always thought the same.

So yes, if we read Duong Quang Ham and others from the 1st half of the twentieth century we can see one thing, but if we read a book like

“Lịch sử Việt Nam” by Ủy ban khoa học xã hội Việt Nam (Hà-nội : Khoa học xã hội, 1971) we can see other things.

In other words, there is no single way that “the Vietnamese” think, or have thought. That said, over the past 1/2 century within Vietnam the idea that the BNDC is some kind of “declaration of independence” has become a widespread belief (I have even been told by certain people high up in academia in Vietnam that it has been affirmed [khẳng định] that this is “declaration of independence #2” – tuyên ngôn độc lạp thứ 2. . .). So whether you like it or not, that view is very widespread.

dear, , In this comment I will write about the way Vietnamese people understand the BNĐC and discuss that is right or wrong way.

First, In our minds, BNĐC is never confirmed officially as a Declaration (you can view some books over “history of Vietnamese Literature”, authors always introduce BNĐC as “written by Nguyen Trai in order to annouce Le Loi’s victory and the way he won the throne” (Duong Quang Ham). If we say (example, in the school text book) BNĐC was a declaration, it will be only a funny comparision to the 1945 Declaration by Ho Chi Minh (which is a way to support the compatriotism).

Second, if we (Vietnamese) do not think about BNĐC as a declaration, how will we understand it? Yes, basically, we start to read it from it’s “genre” and “type” (thể loại và loại hình). A type of a text is defined by its function and A genre of a text is defined by its form. So Type and Genre are different concepts. But in Chinese Classical Literature, “genre” and “type” could have a same name and could be relative. So if a text has a type defined, it MUST belong to a correlative genre. “Đại Cáo” is a type of text, and also a genre of Literature. It was written in a “Đại Cáo” form, and had the “Đại Cáo” function. “Đại Cáo”, originally, was a name of 35th chapter in “Chu Thư” part of “Kinh Thư” book, in which The Duke of Zhou announce his throne to “Thiên Hạ”. Then Đại Cáo was used as a literature genre to officially announce the achievement and a role of a new King. Cáo is also confirmed as a type – along with Hịch, Chiếu, Biểu… – with its own form as we read (example it had an eloquent writting style and an own “niêm luật” – the phoneme connection between sentences …). “Declaration” is a function of text – not a type, a genre. BNĐC could not be a declaration in that meaning, because it didn’t have international background, and simply, it had its own type – genre which did not need “international announcement” function.

Third, after having read BNĐC in its type-genre, we easily define its context: the Spokemans was of course the King and the listeners were “Thiên hạ”. “Thiên hạ” is a complicated subject. First, importantly, it included the court officials. Second, it were all people and non-people (deities, gods…) in Kingdom. BNĐC had two important functions: give a new information of throne-situation (“Xã tắc dĩ chi điện an”) and discuss about rational basis of morality of the New King (“Nhân nghĩa chi cử, yếu tại an dân”). In the other words, it introduced new King and explained that the New King met the Confucian Morality demands.

Fourth, “people” and “traitorous rebels” were not a concrete group of people. These concepts must be understood in morality aspect. “People” were one of subjects of Confucian politics morality. So you are a bad or a good King depends on how you attain peace for your “people” (an dân). “People” never mean the people who the King represent (so King Le Loi did not say “we”). And Rebels were who against the peace of “People”. (Following comment of Winston Phan, Lam Son Thuc Luc said: “Then the enemy/rebel became more ruthless, the people could not survive…”). Rebels (tặc – 賊) was original meaning “damage, hurt” (Thiều Chửu in his famous sino-viet dictionary added: who damage the “People” are 賊) So Ming were traitorous Rebels!

So, my conclusions are:

– Modern Vietnamese people in their minds and in their education understand seriously the BNĐC with its Genre-Type.

– That way of understanding is not wrong.

– BNĐC is an announcement more than a declaration. BNĐC (and Lam Son Thuc Luc) is simply an explanation about why and how Le Loi won the Throne. It emphasized the Confucian morality basis of the new King, in which, wiping out the rebels (Ming) was one of evidence that Le Loi had true reasons to be a new Kingdom leader.

Thanks for the comment.

I completely agree with you that we need to look at it’s genre, and that is exactly what 99% of the writings that I have seen on this document do NOT do. As for the “declaration of independence” view, that is extremely widespread. Nam quoc son ha is “declaration of independence” #1, the BNDC is “declarations of independence” #2, etc.

In terms of its genre, a “dai cao” is not “literature” in the modern/Western sense of a rather innocent type of writing that is meant to express feelings/sentiments. It is a political document, and no political document is innocent. With that in mind, you might want to re-read the “dai cao” in the Kinh Thu. What was the context? Was it just an innocent “announcement” that someone was on the throne? That’s not how I’ve ever seen it explained, and if you read what is actually written there, that is not what it talks about.

So yes, I totally agree with you that we need to look at the BNDC as a “dai cao,” and that is what I will do soon, but when I do, I will try to look at the actual context and purpose of the original “dai cao” and then think about how the BNDC relates to that.

Thanks again!!